Reason #15,926 I love the Internet: it allows us to bypass our insane leaders israelovesiran.com

— allisonkilkenny (@allisonkilkenny) April 22, 2012

Sherry Turkle published an op-ed in the Opinion Pages of the New York Times’ Sunday Review that decries our collective move from “conversation” to “connection.” Its the same argument she made in her latest book Alone Together, and has roots in her previous books Life on the Screen and Second Self. Her argument is straightforward and can be summarized in a few bullet points:

- Our world has more “technology” in it than ever before and it is taking up more and more hours of our day.

- We use this technology to structure/control/select the kinds of conversations we have with certain people.

- These communication technologies compete with “the world around us” in a zero-sum game for our attention.

- We are substituting “real conversations” with shallower, “dumbed-down” connections that give us a false sense of security. Similarly, we are capable of presenting ourselves in a very particular way that hides our faults and exaggerates our better qualities.

Turkle is probably the longest-standing, most outspoken proponent of what we at Cyborgology call digital dualism. The separation of physical and virtual selves and the privileging of one over the other is not only theoretically contradictory, but also empirically unsubstantiated.

The relationships that we curate and maintain online through Faceboook and other social media services are deeply anchored in offline interaction. There is no “second self” on my Facebook profile- it’s the same one that is embodied in flesh and blood. I might make myself look better than I really am, I might even lie, but how is this categorically different than my choice of clothing, the bumperstickers on my car, or a cheesy Hallmark greeting card? You might consider Facebook, bumper stickers, clothing, and Hallmark to be shallow modes of expression, but then deal with all of these symmetrically. What is the underlying social ontology that produces these things? A symmetrical approach, one that looks for antisocial tendencies in digital as well as nondigital technologies, will bring you to radically different conclusions (which I will spell out later).

Additionally, we must not forget that these communication technologies are made by people with explicit kinds of communication in mind. Some may incentivize short-sighted, uncritical thought, but others might be built to support or enable in-person communication. I agree with Turkle when she says “Human relationships are rich; they’re messy and demanding” which is why users are constantly testing and playing with the designers’ original intent. We selectively delete posts, or create multiple accounts in a constant effort to make these sociotechnical systems do what we want them to do. Sometimes we go so far as to build totally new platforms. By ignoring this kind of behavior, Turkle is essentially accusing us of a false consciousness. We are not self aware of our communication technologies, Turkle contends, unless we make active choices not to use them. We are, essentially, sociotechnical dopes. The dope is on full display when she says: “We used to think, ‘I have a feeling; I want to make a call.’ Now our impulse is, ‘I want to have a feeling; I need to send a text.'”

Imagine if we changed the unit of analysis from “communication technologies” to “antisocial technologies.” What might we find? We will have to look for technologies that produce effects and encourage certain processes. Our search might lead us to certain specific material devices, but not necessarily. Studies from around the world (Trinidad, Ghana, United States, Jamaica, Armenia just to name a few) show a rich and heterogeneous relationship between humans and their communication devices. The effects are not all positive, but a lot of them are: enabling closer family ties, allowing youth to find support networks, giving entrepreneurs in isolated regions access to valuable business connections. The internet is not a monolith and we cannot theorize it as such.

We must fight the urge to be techno-utopians as much as we should avoid Turkle’s digital dualism. I actually agree with Turkle on one thing- our augmented society is experiencing a dearth of evocative and meaningful relationships. (Here, when I say “our”, I am speaking in the western context.) Something that we might call “community” is in short supply. Maybe we do hide from ourselves too much, but that happens online as well as off. We are hiding from the people around us at the coffee shop, but we are also hiding from people online. I might block a friend who asks critical questions about my politics. If I am at a coffee shop without a device, I might choose to become intensely interested in my shoe or the ingredients of Vitamin Water. When we do run into people we don’t know, whether its in a suburban gated community (a technology about as old as the internet) or a friend’s timeline, we say and do a wide variety of things. Some are great, some are truly tragic and horrible.

Langdon Winner reminds us that technologies have politics built into them, sometimes those politics are intentional, sometimes they are deliberate. It is certainly useful to ask, “what sorts of politics are built into the Internet?” The internet’s Cold War origins mean its decentralized (to maintain functioning in the event of a concentrated nuclear attack) and it is constantly getting faster because computers were intended to give us the upper hand in making complex, “objective” decisions. This was a time driven by intense paranoia and individualist thinking. But ARPANET is not the social web we have today. There might be some of that cold war thinking deep in the backbone of the internet, but we cannot draw a straight line from game theory to your Blackberry addiction. There is something more fundamental here, something that predates digital technology.

Ultimately, I think we need to reconsider –dare I say it– what technology wants. Both digital and nondigital technologies have the capacity to enable our most antisocial tendencies, or even cause those tendencies. Jacques Ellul thought that before machines and industrial factories, there was an underlying method called technique. Technique is, “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity. Its characteristics are new; the technique of the present has no common measure with the past.” Before someone could invent a technology that let us hide from our surroundings by clicking through “12 more of the most inadvertently sexual sports headlines” there was a desire to entertain our base desires with ruthless efficiency. Turkle herself says, “When we communicate on our digital devices, we learn different habits. As we ramp up the volume and velocity of online connections, we start to expect faster answers.” This might very well be the case. But is it the technology that does it, or is technique, embodied in our email and smartphones, the underlying cause? Can we keep the technology and change the behavior?

This is where the distinction between digital dualism and augmented reality become essential. The digital dualist perspective says no: there is something in the technology that enables/causes antisocial behavior and we must overcome this false consciousness by actively refusing to use our devices. The augmented reality perspective demands that we look at root causes. That might lead us to the same ends: no texting at the dinner table, leave your smartphone at home at least once a week, but it also lets us consider other problems. Maybe your kids are on Facebook because you live in a suburb where you can’t meet another human without driving a car. It also forces us to think of the big picture- I will gladly live in a world where Cape Cod tourists are distracted by Facebook updates if it means disadvantaged groups have tools to reach out and organize across geographic boundaries. Let the rich be alone together, the rest of us will find something to talk about.

You can have deep, meaningful conversations with David on twitter: @da_banks

Comments 46

Jon Stevens — April 23, 2012

"Let the rich be alone together, the rest of us will find something to talk about."

Beautiful. I was agreeing with every word you were saying, and then you fire off this shotgun shell. Well bloody put, David.

Elly — April 23, 2012

This is a great post! It really resonated with me for a few reasons.

1) I have noticed on facebook how a lot of networks/friendship groups are connected to 'RL' relationships. I noticed this from the 'outside' when I set up a FB profile relating to my online presence - my blog. And I realised I had some 'critics' or 'adversaries' on FB they did things like deleted my comments on their walls, or encouraged their FB 'friends' to block me. Due to their RL connections/allegiances. I have yet to set up a FB profile of my RL identity. Or indeed to use that in relation to my online identity.

2) related to this i was 'outed' recently online. so people who know me and my blog, and my internet handle (Quiet Riot Girl) gained information and revealed my RL name and identity. I had not backed this up by being my 'real ' self online, in many arenas, so I felt very exposed and vulnerable.

I think what i am trying to say is that our 'real' selves are very much intwined with whatever we do/say/are online. I challenge anyone who has any kind of online presence to try and separate those complex relationships.

Quiet Riot Girl/Elly

Taylor Dotson — April 23, 2012

David, you make some great points throughout. I'm not surprised to see some of the discussion points from last Wednesday's seminar making its way into your post. We do seem to have quite a number of common interests, in spite of my more pessimistic outlook.

Moving on to your post, I'm not entirely convinced that the separation between "digital dualists" and the position that you consider yourself as championing really exists or, at least, is more of a difference in values rather than theory. I have not read the more recent arguments made by Turkle, Carr and a number of other modern critics of digital communication technology as advocating two separate selves nor presenting a view that lets less advanced technologies off the hook. You quote Turkle herself as stating that the kinds of social interactions, which she finds problematic, are "learned" through the use of devices. Carr's view is similarly developmental. One of the notable quotes in The Shallows is from Neitzsche describing how he finds the affordances of the new fangled communication technology of his era - the typewriter - as subtly nudging him into approaching the practice of writing in a very different way. The fact that they consider the effects as a developmental result of learning is something that complicates the notion of them as merely digital dualists since one's learned behavior can rarely be circumscribed to only one facet of one's life.

The reason they advocate taking a break from technology is to do something very similar to what you advocate. It is to get to the root cause, something that comes neither singularly from the person or the technology but emerges from the confluence of the two. Turkle's issue, in Alone Together, is not technology per se but rather its seductive pull when its affordances meet up too well with our human vulnerabilities. I doubt she would deny that these vulnerabilities existed before cell phones and Facebook but that their characteristics pose special challenges when compared with a newspaper or an Aquafina bottle (perhaps only in degree but I think also in kind). Just like I never realized what effects highly processed and unhealthy had on the way my body functioned until I made efforts to avoid them when possible, I think the point of the practices of refusal proposed by authors like Turkle is to help cultivate a similar awareness of how technologies do augment our reality, enabling the right amount of reflective distance upon which to make our own value judgements. I think this message probably gets lost on many readers because many of these authors own value position on that augmentation is perhaps too distracting and bleeds into their analysis.

I do agree with the sentiments of your post. The political gains that some have made because of network technologies is non-negligible. As well, the effects of technological mediations on human practice, in the short term at least, are unlikely to be mitigated by trying to rid devices from our lives but trying to work out a productive relationship with them (channeling Verbeek here). Nevertheless, I think dismissing Turkle's concerns as only a problem for the rich risks cultivating an active ignorance about an important facet of technology because it is inconvenient to consider it in conjunction with your other political aims. I think there is intellectual room for imagining technologies that do help disadvantaged groups coordinate AND are less enabling of the kinds of social pathologies that Turkle is talking about. Our approach to technology need not be zero-sum either.

Luke Fernandez — April 23, 2012

What an engaging post. It's certainly making me reevaluate Turkle's argument. Still, I find what Taylor Dotson says above pretty compelling. And to segue from his last paragraph I'd hope that there's a way to echo Turkle’s laments while at the same time acknowledging that digital technology has wrought many good things as well. Many of the criticisms that Turkle has made are anticipated by technology critics in the past. But just because they aren't new, doesn't mean they're moot. Nor can we dismiss them simply as the nostalgic sentiments of an Arnoldian elite or of cyberasocials. The aggregate effect of our inventions may have been progressive up until now. But unless one ascribes to a simple form of technological determinism it's a bit foolhardy to think that the human-machine relationship will necessarily proceed on a similar path going forward. Each generation needs to fret through this relationship anew: if we don't we *will* fall prey to what technology wants. That's why there's still room for Turkle and the rest of us fretters in this conversation. We fret not because we're blind to technology's boons, we fret because it's an indispensable part of working out a virtuous relationship between ourselves and our machines.

Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem | Technoculture | Scoop.it — April 23, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px ; background-color:#083a22; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 5:49 [...]

Suzanne — April 24, 2012

"....The separation of physical and virtual selves and the privileging of one over the other is not only theoretically contradictory, but also empirically unsubstantiated. "

The virtual self doesn't exist without a physical self. Or more to the point, the body IS by definition a privileged entity in the mashup of a physical and virtual self. Bodies are inescapable locations of oppression and privilege. Men's bodies rape women's bodies. Fat people bodies are socially inferior to skinny people bodies. Young bodies are revered; black bodies are incarcerated. These are empirically substantiated phenomena, as is the role of embodiment in the development of one's psychology and sense of self.

Turkle is one of the few voices to have actually conducted real research, and over time a period of time. True her lens is limited and limiting like any researcher's.

Elly — April 24, 2012

I can't help but feel that Turkle, and some of the commenters here, are missing an important point of D A Banks' argument.

It is a point I have read in the work of Nathan Jurgenson et al too. That is, that in the 21st century wired up world, our 'bodies' and our 'selves' have been and continue to be transformed by technology, and our interaction with it.

This theory of 'embodiment' is left over from the pre-internet age. Judith Butler wasn't on twitter when she wrote Gender Trouble. Everything is changing and how we define ourselves and even exist physically in the world is transforming. I thought that is what 'cyborgology' meant.

Dale — April 24, 2012

When you say : "Sherry Turkle published an op-ed in the Opinion Pages of the New York Times’ Sunday Review that decries our collective move from “conversation” to “connection.” ", I have a little bit of an argument with that. In her book, at least, she highlights that the problem is not CONNECTION per-se, but HYPER-connection. And on this score, I have seen, even as a "hyper-connected" person myself, that many. many people have indeed allowed the convenient affordances of online communication affect their way of relating to people. And this is not always a good thing. Even Howard Rheingold stresses in his introduction to his book Net Smart, that it is very easy to let this digital age adversely affect our relationships (and I realize that I venture close to "dualism", and almost said "affect our day to day lives" (as if digital is not already a key component of day to day, or the deeper implication being: "Normal life")

I simply can't help but think that the "ferocity" of her cautionary warnings are taken too singularly, apart from her insights of earlier works. Because of having read "Life on the Screen" and many articles about "The Second Self", and the insight I gained from those, coupled with a decade of hyper-connectivity in society since the rapid adoption of smart phones, and the unmistakable shift in social habits because of it, I feel resonant with her feeling that this has been such a good thing. I continue to enjoy what I consider good, and be hopeful for increased affordances, but neither can I join the choruses of people attacking what seems to them to be "curmudgeony" resistance. I am anything but, yet I cannot help but notice when people use technology and texting/email as a filter for people to wish they don't wish to speak. Not that this never becomes neccessary, but it has become a much too easy way of eliminating pesky conversations. Maybe the people dong these critiques are less often at the recipient end of "digital put off" as I perceive myself to be, but it does tend to make one shake their head at how much easier it is to be a dick (in a "nice way") -- and that last comment is not directed at this article or post, but at the ones who use digital communications as a way of filtering out people to the extent that they basically just ignore/exclude people who they would not be so quick to be so dismissive face to face.

Dale — April 24, 2012

"Similarly, we are capable of presenting ourselves in a very particular way that hides our faults and exaggerates our better qualities."

Frankly, I don't see how you can have much of an argument with this. Best example: Facebook.

Dale — April 24, 2012

"A symmetrical approach, one that looks for antisocial tendencies in digital as well as nondigital technologies,"

Yes, but Turkle does not locate the anti-social in the technologies, but in our appropriations of them (at least in these works which are now under fire)

Dale — April 24, 2012

"I will gladly live in a world where Cape Cod tourists are distracted by Facebook updates if it means disadvantaged groups have tools to reach out and organize across geographic boundaries. Let the rich be alone together, the rest of us will find something to talk about."

Ahh... there we have it. The old "elitist" card again. Well, you know what? I've never made over 60k a year , and I still share her concerns. So that is a useless assessment that devalues the rest of your argument (in which I have much more interest and hold in higher regard)

Social Blend » Blog Archive » 198: The Blendology — April 26, 2012

[...] Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem [...]

Does Mommy Need a Social Media Diet? (Why Modeling Matters) | The Digital Media Diet — April 26, 2012

[...] Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem, [...]

Facebook makes us lonely, debate is heated up again | Yuli Patrick Hsieh — April 26, 2012

[...] Banks, Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem at The Society [...]

U Resist — April 29, 2012

I read this article on my phone.

Sélection de la semaine (weekly) - Demain la veille — May 13, 2012

[...] Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem » Cyborgology [...]

Reaction: Turkle, Tufekci and Marche on the Diane Rehm Show » Cyborgology — May 14, 2012

[...] This takes me to the main take-away from this hour of radio, and it is a major disconnect between how Turkle/Marche and Tufekci fundamentally understand the relationship between the on and offline. On one side, there are those who see someone on Facebook or texting and assume they are removed from the offline, physical world. This is the zero-sum view of the on/offline: the more time you spend online, the less offline; we are trading one for the other. The term I coined to capture this assumption is “digital dualism,” that the on and offline are separate and thus one displaces the other. David Banks also compellingly made this point in reaction in to Turkle: “Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem.” [...]

Sherry Turkle’s reproductive futurism | Tyler Bickford — May 16, 2012

[...] is that children are being harmed. (Others do a better job than I can critiquing Turkle’s “digital dualism” problem, like when she describes “bailing out from the physical world” in the TEDx talk below, [...]

Digital Dualism and Stories of the Real » Cyborgology — May 24, 2012

[...] Furthermore, I think the reasons why this assumption is incorrect have some things to say regarding the problematic assumption of digital dualism. [...]

Some quick thoughts about sociological realism and digital life | The Sociological Imagination — June 29, 2012

[...] reasons for this distinction, which has pithily been named digital dualism, are a fascinating question in their own right. In part I think it stems from [...]

Will Facebook prolong our lives? - MindLeadersMindLeaders — July 10, 2012

[...] that comes with social networking is unhealthy. A down-side to social networking, according to Prof. Sherry Turkle of Massachusetts IT, is that “We use this technology to structure/control/select the kinds of conversations we have [...]

Cyberbullying is an Old Lady Word » Cyborgology — July 11, 2012

[...] and it’s yet another clear case of what other authors on this blog have described as digital dualism. In the Internet safety arena, digital dualist frames do not simply draw distinctions between [...]

Why Children Laugh at the Word “Cyberbullying” » Cyborgology — July 14, 2012

[...] and it’s yet another clear case of what other authors on this blog have described as digital dualism. In the Internet safety arena, digital dualist frames do not simply draw distinctions between [...]

A State of Comfortable Change | Writing Through the Fog — July 22, 2012

[...] this all smells of “digital dualism”—me looking in, observing my new life unfold in status updates and Instagrams and updated social [...]

Possibility vs. Potentiality: A Case Study in Documentary Consciousness » Cyborgology — July 26, 2012

[...] to the point of being simply “relationships” that include both online and offline interaction. Digital dualists (those who believe online and offline are separate worlds or realities) would do well to observe [...]

Dear Stihl: I’m Already Real, Thanks » Cyborgology — August 16, 2012

[...] Sacasas goes on to note that in art and literature that deal with pastoral themes, the encroachment of industrial technology is often presented with a certain degree of gentle threat or melancholy; it’s a kind of memento mori for rural American life, and a recognition that the world is changing in some fundamental and irreversible ways. Inherent in this is a nostalgia for the American pastoral, a sense that life lived within that context was somehow better and more real, as well as more communal. The pastoral was fetishized in much the same way that “IRL” is now, and its perceived loss was mourned in ways that should be familiar to anyone who’s read Sherry Turkle. [...]

Some quick thoughts about sociological realism and digital life | Digital Researcher — September 24, 2012

[...] reasons for this distinction, which has pithily been named digital dualism, are a fascinating question in their own right. In part I think it stems from [...]

[Book Review] Invisible Users: Youth in the Internet Cafés of Urban Ghana » Cyborgology — October 25, 2012

[...] many Western authors see the internet as a force for dividing and individuating, the Internet appears to be competing with major religions for the same sorts of tangible and [...]

Cyborgology Turns Two » Cyborgology — October 26, 2012

[...] 8. Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem [...]

Strong and Mild Digital Dualism » Cyborgology — October 29, 2012

[...] and my IRL Fetish essay is perhaps the deployment of digital dualism that I’m most proud of. David Banks, Zeynep Tufekci, Jeremy Antley, PJ Rey, PJ again, and too many others to list here have also [...]

Thousands, nay millions, alone together « pterostichini — November 8, 2012

[...] guess I am more of an augmentist than a digital duelist dualist. Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in ETS [...]

A (Semi-)Augmented Festival: Twitter, Instagram, and Cybersociality at Iceland Airwaves 2012 » Cyborgology — November 9, 2012

[...] statements I couldn’t tweet and cropping photos into square-shaped images I couldn’t post). Some people might claim that this is because digital sociality has destroyed my ability to interact with other [...]

Digital Dualism For Dummies: #1 You Dawg, I Herd U Like Theory… « Foucault's Daughter — November 11, 2012

[...] been preoccupied by the ideas and theories currently being developed by Nathan Jurgenson and other writers at the brilliant cyborgology blog. One of the concepts put forward by Jurgenson and colleagues [...]

Social Blend » Blog Archive » The Best of Social Blend 2012 — December 12, 2012

[...] Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem [...]

» The Best of Social Blend 2012 - The BlendoveR Podcast — December 21, 2012

[...] Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem [...]

Personal Learning Networks: Knowledge Sharing as Democracy | Collaboration | HYBRID PEDAGOGY | Teachers TechTeachers Tech — January 5, 2013

[...] dualism. As David Banks at Cyborgology suggests, it may be more appropriate instead to consider our technique—how we useRead More: http://hybridpedagogy.com/Journal/files/Personal_Learning_Networks.html [...]

Origins of the Augmented Subject » Cyborgology — January 15, 2013

[...] is somehow separate from the reality we all inhabit. (We use Nathan Jurgenson’s term “digital dualists” to describe people who characterise the Web thusly.) Early dualist fiction writers imagined [...]

AUGMENTED SELF « IDentifEYE — January 19, 2013

[...] Subject. They argue against a dualism in our identities - We use Nathan Jurgenson’s term “digital dualists” to describe people who characterise the Web thusly – and rather accept the concepted of a [...]

#TtW13 Presentation Preview: On the Political Origins of Digital Dualism » Cyborgology — March 8, 2013

[...] New York Times’ article about the New Digital Divide and the Knights of Columbus sound a lot like Sherry Turkle. Both quotes, Turkle, and the New York Times all share a common set of prerequisite assumptions. [...]

» the Digital Dualism *Discussion*, Part Three MePhiD — March 10, 2013

[...] as “probably the longest-standing, most outspoken proponent” of digital dualism (Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem, April 23, 2012) and repeatedly mentioned in several of the posts and responses above. Admittedly, [...]

My Digital Dualism Fallacy — July 5, 2013

[...] one half of a binary in which the other half has to deny unification. Sherry Turkle – who is “probably the longest-standing, most outspoken proponent of what we at Cyborgology call digital du... – doesn’t believe that logging into Facebook initiates some sort of trans-dimensional migration [...]

Cyborgology Turns Three » Cyborgology — October 26, 2013

[…] 9. Sherry Turkle’s Chronic Digital Dualism Problem […]

A Social Critique Without Social Science » Cyborgology — November 11, 2013

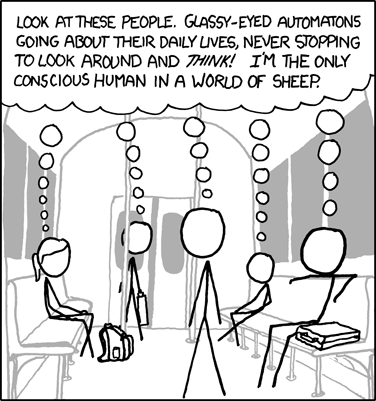

[…] seeing today’s XKCD (above) I sort of wish I had written all of my digital dualism posts as an easy-to-read table. I generally agree with everything on there (more on that later), but […]

A Social Critique Without Social Science | David A Banks — March 6, 2014

[…] seeing today’s XKCD (above) I sort of wish I had written all of my digital dualism posts as an easy-to-read table. I generally agree with everything on there (more on that later), but […]

Dualismo digital: el antagonismo entre el mundo ‘offline’ y ‘online’ | TICbeat — August 14, 2014

[…] otro lado, los detractores de la teoría ofrecen una perspectiva totalmente distinta. Según algunos autores nuestras vidas detrás de las pantallas carecen de importancia por ser un intento de sustituir las […]