The Facebook newsfeed is the subject of a lot of criticism, and rightly so. Not only does it impose an echo chamber on your digitally-mediated existence, the company constantly tries to convince users that it is user behavior –not their secret algorithm—that creates our personalized spin zones. But then there are moments when, for one reason or another, someone comes across your newsfeed that says something super racist or misogynistic and you have to decide to respond or not. If you do, and maybe get into a little back-and-forth, Facebook does a weird thing: that person starts showing up in your newsfeed a lot more.

This happened to me recently and it has me thinking about the role of the Facebook newsfeed in inter-personal instantiations of systematic oppression. Facebook’s newsfeed, specially formulated to increase engagement by presenting the user with content that they have engaged with in the past, is at once encouraging of white allyship against oppression and inflicting a kind of violence on women and people of color. The same algorithmic action can produce both consequences depending on the user.

For the white and cis-male user the constant reminder that you have some social connection to a racist person might encourage (or at least afford the opportunity that) you take that person to task. After all, white allyship is something you do, not a title that you put in your Twitter bio. There are, of course, lots of other (and better) ways to be an ally but offering some loving criticism to acquaintances and loved ones can make positive change over time. It is almost, for a moment, as if Facebook has some sort of anti-racist feature: something that puts white men in the position to do the heavy lifting for once and confront intersecting forms of oppression instead of leaving it up to the oppressed to also do the educating.

The same algorithmic tendency to continually show those you have interacted with, as if all intense bouts of interaction are signs of a desire for more interaction, can also be an instigator and propagator of those same sorts of oppression. An argument can turn into a constant invitation for harassment because, just as you see more of your racist acquaintance, so too do they see you. This could lead to more baiting for arguments and more harassment. But even if this does not happen, the incessant racist memes that now show up in your timeline are themselves psychically exhausting. This algorithmic triggering –the automated and incessant display of disturbing content– is especially insidious because it is inflicted on users who stood up to hateful content in the first place.

This agnosticism towards content in favor of “engagement” for its own sake is remarkably flat-footed given all the credit we give Facebook for being able to divine intimate details and compose them into a frightening-as-it-is-obscured “graph” of our performed self. If we wanted to keep the former instance (encouraging ally behavior) but reduce the possibility of the latter (algorithmic triggering) what might we request? How can something like Facebook be sensitive to issues of race, class, and gender?

One option might also use some sort of image-recognition technology that gives the user the option to unhide a hateful image rather than see it by default. If Facebook can detect my face it can certainly detect the rebel flag or even words printed onto image macros. Yik Yak, for example, does not allow photos of human faces and implements that rule through face detection technology. If your photo has a face in it, the app doesn’t let you post it. If a social media company can effectively weather free speech extremists’ outrage, they might be able to impose some mild palliatives to potentially upsetting content.

The problem with these interventions is that it requires that Facebook collect and act on even more information. It asks that Facebook redouble their efforts to collect and analyze data that determines race and ethnicity. It asks them to study photos and proactively show and hide them. It also falling into some of the issues I’ve raised in the past about trying to write broad laws to eliminate very specific kinds of behavior. That seems to be the wrong direction.

The Occam’s razor solution is to have Facebook adopt some sort of anti-racist and/or anti-sexist policy where it pits those people who have demonstrated anti-racist tendencies, against those with more retrograde viewpoints. The algorithm could be tweaked so that white people who have espoused anti-racist sentiments in the past are paired with their “friends” that think the confederate flag is about heritage or whatever. Men who have shared content with a feminist perspective could be paired with men who wear fedoras. All the while controlling and modulating who sees whom so that the burden of teaching and consciousness-raising isn’t unevenly distributed to those that bear the brunt of hate.

This actively imposed context collapse is admittedly improbable –I know there’s no chance that Facebook would decide to do this—but thinking through the implementation of such a policy is a good thought experiment. It highlights the embedded politics of Facebook—a platform that would rather have us be happy and sharing than critical and counterposed. Engagement with brands not only requires active contributions to the site, but positive feelings that can be usurped for the benefit of brands. Deeper still, social media as an industry is deeply committed to the “view from nowhere” where hosts to conversation are only allowed to intervene in the most egregious of circumstances, almost always as a reaction to a user complaint, and never as part of a larger political orientation.

Even the boardroom feminism of their own Sheryl Sandberg is largely absent. As far anyone can tell, there is nothing in the Facebook algorithm that encourages women to “lean in” in Facebook-hosted conversations. Such a technological intervention –and we could have fun thinking about how to design such a thing– could have done just as much, if not more, than the selling of a book and a few TED talks. For example, imagine if Facebook suddenly put the posts and comments of self-identified women at the top and buried men’s. Maybe for just a few days.

Perhaps we should simply cherish and make the most of the moments when the algorithms in our lives start inadvertently working towards the betterment of society. I’m going to keep calling out that racist person on Facebook and while that certainly doesn’t qualify me for a reward or really even a pat on the back, it is (for me) something that doesn’t take a lot of time or effort and might possibly make the world (or that one person) marginally better.

I do not think anyone, at the present moment, is suited to offer a viable proposal for leveraging the Facebook algorithm to promote allyship or even reduce what I’ve been calling algorithmic triggering. Those with the relevant backgrounds, either through formal education or past experience, are missing from the board rooms where the salient decisions are being made. Conversely, those in the board rooms that actually know how the algorithm works, what it is capable of, and are poised to monetarily gain (and lose) from Facebook’s ability to attract advertisers are not necessarily the best people to make these sorts of political design choices. Perhaps the best way to think of algorithmic triggering is the automation of “if it bleeds it leads” editorial choices. The decision to show violent and disturbing video (of police officers murdering black people for example) can be motivated by good intentions but can lead to an impossibly cruel media landscape. Obviously we should all be fighting to end the events that are the subject of this disturbing media but for now we would do well to demand that the gatekeepers of (social) media take our collective mental health into consideration. What that looks like, is yet to be seen.

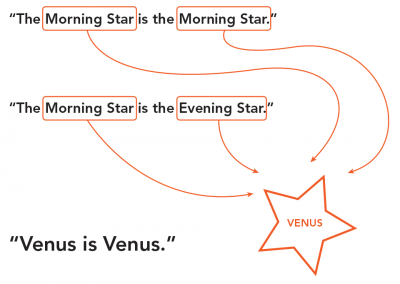

Should automated reasoners assume that a reference to Bruce Jenner is the “same as” a reference to Caitlyn Jenner, or that a reference to Burma is the “same as” a reference to Myanmar – that the two have the same “identity”? And more importantly, who gets to decide? What happens when this sameness organizes how we see data on the Web? Or when it becomes the basis of research conducted on the Web?

Should automated reasoners assume that a reference to Bruce Jenner is the “same as” a reference to Caitlyn Jenner, or that a reference to Burma is the “same as” a reference to Myanmar – that the two have the same “identity”? And more importantly, who gets to decide? What happens when this sameness organizes how we see data on the Web? Or when it becomes the basis of research conducted on the Web?