In the beginning, there was nature. And in spite of the obvious lack of humans to give names to the animals and to categorize the trees, it all basically looked and felt like it does now: Leaves were green and rocks were heavy. Over time, humans (those natural tool makers!) developed a plethora of explanatory concepts and ways of knowing that gave their universe a discernable order. At different times and in different regions of the world, the universe took on vastly different shapes and personalities. There were the four humors, animism, Feng shui and by the mid 1660s some white guys had developed something called experimental philosophy. Today we just call it the scientific method. One of those white guys, Robert Boyle, was particularly vocal about the benefits of the scientific method and objective observation.[1] He believed deeply that if enough men[2] of reputable repute watched something happen, you could call it true. No monarch or bishop required. Thomas Hobbes was skeptical. Not because he believed truth had to come from an authority figure, but because he was, among other concerns, suspicious that by observing effects one could derive the underlying physical causes. While both men had strong and informed opinions about society and the natural world, today we remember Hobbes as a political philosopher and Boyle as one of the first modern scientists. The separation of society and nature didn’t have to look the way it does, but historical and social circumstances encourage us to separate these two realms.

I just think that’s an interesting story.

It shows that fundamental orienting concepts are tenuous and contingent. Had Hobbes convinced the right people, Western society would look very differently. We might arrive at truth through a completely different process and the material artifacts that we produce would be regarded in a totally different light. When you get down to it, the only important rubric for a Theory of Everything is that it is reliable: That the conclusions that it draws can do meaningful and/or productive work. A professor of mine had a saying: “You can use witchcraft and western science to get to the moon, but only one of them are likely to work.” Disagreements over how to talk about digital technologies and social action have a similar valance. Sometimes it looks like a semantic argument, but there are key differences that can make an analysis more accurate more of the time.

Mr. Nicholas Carr has decided to levy a flatteringly thorough rebuttal to the theory of augmented reality (you know, that thing we’ve been tinkering with in “fits and starts”) on the eve of Cyborgology’s 3rd annual Theorizing the Web conference. Naturally, all of us are busy preparing for the conference and therefore are unable to mount a complete and total rebuttal of Mr. Carr’s recent blog post. I’ll attempt to tackle some of his more egregious misunderstandings and errors today. Most of this is written from memory of the various documents in question, so I offer my advanced apologies for any incongruities, misspellings, or over-simplifications. More comments and posts can be expected and I’ll happily append this post if someone catches an error.

In his post, Digital Dualism Denialism, Mr. Carr asserts that ignoring the separateness of the online and the offline is “wrongheaded” and to act as though the distinction is totally meaningless is to ignore key facets of what digital technologies afford and allow. I agree with that, and I’d say most of my fellow writers do too. It sounds as though Mr. Carr is debating William J. Mitchell more than he is arguing with Nathan Jurgenson, myself, or the rest of Cyborgology.[3] Digital dualism is not just about the online and offline being “completely isolated worlds” and we never said as much. What we have said, is that there is no Second Self, or “cyberspace”; there’s just you and the environment. We are just as augmented as we ever were. Mr. Carr gets it wrong in the very first paragraph of his piece when he says,

As Net access has expanded, to the point that, for many people, it is coterminous with existence itself, the line between online and offline has become so blurred that the terms have become useless or, worse, misleading. When we talk about being online or being offline these days, we’re deluding ourselves.

The spatial metaphor of “cyberspace” is and always has been misleading. It is worth noting that the first instance of the phrase “online” was used to denote whether or not a city or town had a train station. You were considered “online” if a train stopped in your town, regardless of whether or not you used the train or the train station was on the other side of town from where you lived. We should probably think of our selves in a similar fashion. If you can conceivably access the Internet, you are online. It doesn’t matter if you’re signing onto a BBS in the 80s or Facebook today.

To wit, there was never a new and totally untouched cyberspace waiting to be populated. Digital networks were born into and are constitutive of the same social and cultural structures and patterns that exist outside of them. When we, as theorists and popular authors, ignore this fact, we tend to become determinist in our thinking. Technology has its affordances, and sometimes those new affordances enable new social practices or make existing ones more prevalent, but we should be extremely careful when making claims about technology’s ability to (just to pick a random example) make us all stupid.

Mr. Carr has accused me in particular of treating people as dopes. That I am ignoring what people feel and instead trying apply an overwrought, “torturous” argument about sexual deviance. This is not even close to accurate. I am simply stating that the Internet (and indeed many new technologies) appears as an addition to an already completed whole and that perception can make it seem superfluous or unnecessary. This perception also has the tendency to make dismissals of related social action easier.

To think as much is to deny not only the real and tangible benefits of the technology, but also the wide and varied experiences that people have with that technology. Yes, some people feel that the digital erodes “the real” and some even see it as an intrusion, but that is just one of literally millions of experiences. Without a hint of sarcasm, authors will describe how their vacations to Cape Cod and Madrid have been ruined by what they view as the anti-social properties of iPhones, while at the same time excoriating youth and the poor for “wasting time” on entertainment and social media. Cyborgology’s contributors should be the last people you accuse of dismissing people’s concerns.

I am not in the business of speaking for others in this arena. So rarely do people in that line of work retire that openings are few and far between.

It is important to be explicit and clear about whom you’re talking when you say “we” or “us” or “our.” These are implicit (and sometimes explicit) declarations of in-group status. There cannot be a “them over there” without an “us over here.” So when you say, “We sense a threat in the hegemony of the online because there’s something in the offline that we’re not eager to sacrifice,” I wonder two things: 1) if you intended to use hegemony incorrectly, and 2) that what you are really referring to is a change of power distribution and ability to speak and not a change in technological affordances.

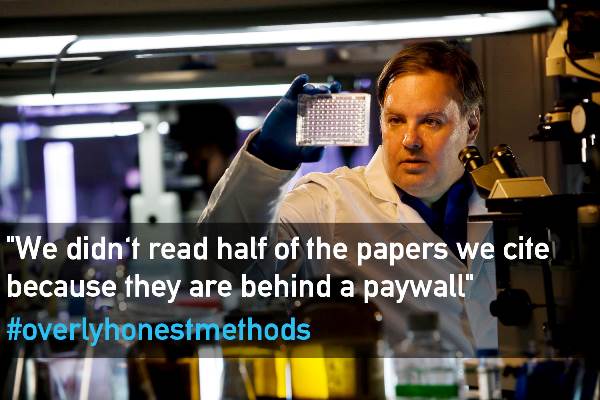

Perhaps this all comes down to a fundamental misunderstanding of our intentions or motivations. I won’t speak for my fellow Cyborgologists, but I am fairly certain that none of us are techno-utopians. Nor do I think any of us would conflate technological innovations with social progress [pdf]. I wouldn’t even characterize myself as a technophile. Rather, I am motivated by the possibility that certain technological affordances and access to resources can induce human flourishing and liberatory potentials. So when I hear that Cape Cod is a little less comfortable or that sitting down to read War and Peace is a little more difficult I don’t really care. When computer networks allow the government to make very specific choices about what food stamp recipients can buy, I care. But I am critical of the sociotechnical apparatus and underlying ideology, not just the computer networks. When I see my students citing Wikipedia or constructing sloppy sentences I seriously reconsider the pace of my assignments and the quality of my pedagogical decisions. I do not jump to the conclusion that they are lazier or less disciplined than are my peers or me. Perhaps I’m being hypocritical for churning out a response within 24 hours, but I know if I don’t get this out today, I never will.

I have not even addressed the fact that Mr. Carr does not appear to understand the use of ideal types (he calls them strawmen), or that to build a typology of digital dualism and augmented reality bookended by such theoretical constructs is not a concession but a clarification. That’s all I’ll say about that.

In the end, I’m happy that this discussion is happening out in the open and not in obscure academic journals. Derrida would probably say something about the inherent contradiction of complaining about the Internet on the Internet, but I’ll let that stand on its own. Mr. Carr ends by posing two short questions: What’s lost? What’s gained? It is important to note that, like energy, most things are not totally lost or created from nothing. They are shifted, reassigned, reallocated, and reconstructed in new and unfamiliar ways. Perhaps what Mr. Carr sees as a loss is a gain to others? Perhaps some of us are, in fact, alone together or are suffering from Google-induced stupidity. But there are also under-socialized and shy kids finding communities that understand them. Doctors in Ghana are staying in contact with patients and giving medical advice to the immobile. I’m not interested in a cost-benefit analysis of every technology, but I do need a theoretical perspective with enough resolution and nuance to account for the multitudinous possibilities that lay before us. It might be fun to play Thoreau and sit in judgment of what the Internet does to people, but I’d rather be a cyborg than a romantic.

David A Banks is on Twitter.

[1] If he were alive today, Boyle would have a million views on his TED talk.

[2] The paintings of the time, like the ones done by Joseph Wright of Derby, portray this very well. Women are in the paintings, but they are often depicted as terrified or grief-stricken as they watch animals suffocate during air pump demonstrations.

The whole case is shot through with evidence of our augmented society. Pictures were posted to Instagram, videos were uploaded to YouTube, and the victim reportedly pieced together the night through Twitter, Facebook and text messaging.

The whole case is shot through with evidence of our augmented society. Pictures were posted to Instagram, videos were uploaded to YouTube, and the victim reportedly pieced together the night through Twitter, Facebook and text messaging.  This optimism is undergirded by what PJ Rey (

This optimism is undergirded by what PJ Rey (