This is the first in a series of autobiographical accounts by Cyborgology writers of our early personal interactions with technology. Half autoethnography, half unrepentant nostalgia trip this series looks at what technologies had an impression on us, which ones were remarkably unremarkable, and what this might say about our present outlook on digitality.

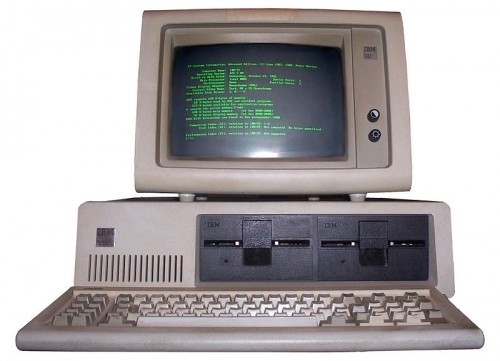

I wish I could say it was love at first sight when my Dad brought home what I just now leaned was called an IBM 5150. According to IBM, “ it was dramatically clear to most observers that IBM had done something very new and different.” I guess I wasn’t most observers. My parents say I liked it but my memories of it little to do with it being a computer per se. It was inculcated in major events in the household. It could make grayscale banners and quarter-page invitations, letters to pen pals and family. Nothing about that computer, for me, had to do with programming. In fact, what I remember most about it was how mechanical it was: All the different, almost musical sounds it made when it was reading a floppy or printing something on its included dot-matrix printer. The spring-loaded keys on its impossibly heavy keyboard made the most intriguing sound; when all ten fingers were on that keyboard it sounded like a mechanical horse clacking and clinking. My favorite part of the computer was when you’d turn it off and it would make a beautiful tornado of green phosphorus accompanied by a sad whirling sound. It sounded like this almost-living thing was dying a small death every time you were finished with it. I loved killing that computer.

I wish I could say it was love at first sight when my Dad brought home what I just now leaned was called an IBM 5150. According to IBM, “ it was dramatically clear to most observers that IBM had done something very new and different.” I guess I wasn’t most observers. My parents say I liked it but my memories of it little to do with it being a computer per se. It was inculcated in major events in the household. It could make grayscale banners and quarter-page invitations, letters to pen pals and family. Nothing about that computer, for me, had to do with programming. In fact, what I remember most about it was how mechanical it was: All the different, almost musical sounds it made when it was reading a floppy or printing something on its included dot-matrix printer. The spring-loaded keys on its impossibly heavy keyboard made the most intriguing sound; when all ten fingers were on that keyboard it sounded like a mechanical horse clacking and clinking. My favorite part of the computer was when you’d turn it off and it would make a beautiful tornado of green phosphorus accompanied by a sad whirling sound. It sounded like this almost-living thing was dying a small death every time you were finished with it. I loved killing that computer.

That was the only home computer I had until about the 7th or 8th grade when something amazing happened and the price of computers plummeted right into my families’ price ranges. Before that, the only computers in my life were at school or at my grandmother’s house. Growing up in South Florida meant your schools were perpetually overcrowded, underfunded, over air conditioned, and understaffed. To have a classroom with a working computer in it, let alone two or three, was nothing short of a miracle. Often times you had a computer that just didn’t work. It just sat in the corner of the room as some sort of alter to a free market god that —if appeased correctly— might bless these children with the capacity to innovate and/or produce well-typed letters for our future bosses.

That god was appeased (I assume) by trips to the computer lab. Those were strange and frustrating times because you were plopped in front of this machine to do one boring task even though you knew could do seemingly anything. (This included a mythical and mysterious pleasure-giver called “Oregon Trail.” If you were lucky and sneaky enough to get to this program, so we told each other, you could shoot things and name characters after people you did not like who would then get horrible fatal illnesses.) I remember preferring ClarisWorks over Microsoft Office and I would never know a love like I had with Hyperstudio until I visited my grandmother and her Compaq Presario which ran a Crayola-branded drawing application that let me draw countless rocketships. That was a very important computer in my life.

Computers were always things that helped me make stuff. I couldn’t care less about actually programming the things. The hardware was interesting though. I always wanted to build my own computer but the closest I ever got was upgrading the memory and installing a DVD-RW drive. One time I replaced a hard drive. I should say more about that hard drive.

In high school I fell into a bad crowd, which is to say, I started hanging out with computer nerds. Instead of doing reckless things that would get me in trouble but ultimately form some very healthy boundaries about what is achievable in life, I spent my summers inventorying thousands of computers and troubleshooting hundreds in preparation for the upcoming school year. During the year I staffed the school’s “help desk” which empowered me to roam the school at all times immune from hall passes. I was allowed to do almost anything so long as I claimed it was in the name of fixing a Powermac G3.

Every student had to wear their student ID around their neck on a lanyard. It was a quick and easy way to process students in a school of about 2000 that was originally meant for 500. All the IDs were the same except for a handful of clubs and organizations that got special codes which acted as talismans in the hallways. The guards left you alone and the administrators never asked where you were going. I even bought coffee from the vending machine in the teachers’ lounge. I was drunk on power. My diplomatic immunity opened too many doors. One such door was the room that housed all of the security monitors. I was asked to replace a monitor in this secret, high security room. I felt like the world’s most boring secret agent but it was wonderful. I had, as Gramsci might say, made a decision to serve high school hegemony in exchange for being exempted from its worst features.

It was sometime after fixing the security cameras that the school’s resource officer offered to pay me real money to fix his computer. I gladly did it, poorly, and for a Geeksquad amount of money. I was over the moon. I had gotten paid to do something I liked. It was a new and unique sensation that I’ve been chasing for the rest of my life. I think that might have also been the first time I thought about the thing that I’d eventually learn to describe as “social capital.”

My first at-home Windows machine was a frankenstein computer made by my mom’s engineer friend. It ran Windows 3.1 and, as far as I was concerned, was largely a Sim City device. I also loved organizing things into folders and changing the color theme. I was a weird kid. This was also the first computer that gave me regular access to the Internet. Or, to be more specific, AOL. That computer was eventually stolen and replaced with another frankenstein. My first corporate computer was a Dell XPS T600R. It could read and write to CD-RWs which, at the time, meant that I absolutely needed to do two things: 1) back up every terrible piece of fiction I had written thus far and 2) burn MP3 CDs of my pirated music to play in my 1993 Mercury Topaz. I played so much Talking Heads in that Topaz.

My first at-home Windows machine was a frankenstein computer made by my mom’s engineer friend. It ran Windows 3.1 and, as far as I was concerned, was largely a Sim City device. I also loved organizing things into folders and changing the color theme. I was a weird kid. This was also the first computer that gave me regular access to the Internet. Or, to be more specific, AOL. That computer was eventually stolen and replaced with another frankenstein. My first corporate computer was a Dell XPS T600R. It could read and write to CD-RWs which, at the time, meant that I absolutely needed to do two things: 1) back up every terrible piece of fiction I had written thus far and 2) burn MP3 CDs of my pirated music to play in my 1993 Mercury Topaz. I played so much Talking Heads in that Topaz.

That was also the computer that introduced me to obsolescence. I was bragging about the computer’s roomy 12gig hard drive to the kid sitting next to me in “web design class” but he just cocked his head, squinted his eyes and said, “why is your computer such a piece of shit?” That was harsh. I should also mention that “web design class” never taught us web design because the room didn’t have a working internet connection. The class consisted of memorizing HTML tags and practicing typing on whited-out keyboards.

—

The first time I ever looked at porn on the internet was on an iMac, my first chatroom was on that Dell XPS. I made a web site for my fiction writing using Microsoft Frontpage before switching to Macromedia’s Dreamweaver. I wrote shitty fiction and tortured LiveJournal posts on all of my home computers. I had different AOL user names depending on which parent I was staying with at the time. That meant the online identity I cultivated on weekdays, everything from bookmarks to contact lists, was different from the one I used on weekends and holidays. Sometimes I’d make a brand new one and “surf the web” as a stranger.

Of course, as a cis-white male, I was always reminded that these devices were made for me. That the love of technology was an easily obtainable social norm for the dumpy, socially awkward teenager. Even if you lost the election to the web design club you founded (I lost to the guy that eventually invented Grooveshark so, in retrospect, he was much more qualified) there was no reason for shame. The world was increasingly mediated and controlled by computers and so masculinity was quickly conforming to that new locus of power. I’m still not sure if I’ve ever felt more personally satisfied than when I convinced my high school’s IT coordinator to give me the network’s master password. I was never so surprised by the success of my work than when a last-minute all-nighter produced an award-winning web site about alternative energy. (I won a Dell Axiom PDA for that, which I sold on eBay to buy Star Trek merchandize.)

Sometimes my mom would let me borrow her beeper so I could hang out at the mall with my friend while she was at work. I wore that thing so prominently and checked it unnecessarily so often that I wore out its only button. My first cell phone was one of those indestructible Nokias. The cover was a silvery-blue and I always had plans to get a different case at the mall (maybe something with a ska band on it?) but those lofty goals never materialized. The cell phone was rarely used for friends. It was mainly a logistics tool for my parents. I don’t have any data to back this up, but I have to believe that divorced house holds greatly contributed to the rapid adoption of cell phones: You could call your kid directly with little-to-no chance of having to talk to your ex. Brilliant.

To date I’ve had seven cell phones and each purchase was made after careful research and an unflattering amount of product review reading. My last three phones have been iPhones but only begrudgingly so (I have small hands and can’t stand most of the Android versions of important apps). Cell phones have always meant a lot to me, even though I hate talking on the phone. I find myself imprinting a small portion of my love for people onto the device that connects me to them. When I switch phones I get a pang of nostalgia. Not for the phone itself, but for the news I got on it. The anxious moments I stared at it waiting for a crush to text me; the bizarre friendship I made with someone who also owned the Motorola PEBL; the phone I used to tell my parents I was engaged. These are intimate moments that are about people, but are mediated through these tiny devices. Its like missing your first car or your shitty apartment right after college.

To date I’ve had seven cell phones and each purchase was made after careful research and an unflattering amount of product review reading. My last three phones have been iPhones but only begrudgingly so (I have small hands and can’t stand most of the Android versions of important apps). Cell phones have always meant a lot to me, even though I hate talking on the phone. I find myself imprinting a small portion of my love for people onto the device that connects me to them. When I switch phones I get a pang of nostalgia. Not for the phone itself, but for the news I got on it. The anxious moments I stared at it waiting for a crush to text me; the bizarre friendship I made with someone who also owned the Motorola PEBL; the phone I used to tell my parents I was engaged. These are intimate moments that are about people, but are mediated through these tiny devices. Its like missing your first car or your shitty apartment right after college.

I’ve had nothing but Nintendo consoles until I got a PS3 in 2007. My Nintendo was a hand-me-down. The Super Nintendo, Nintendo 64, and Game Cube were all holiday presents. I bought a Wii for my fiancé two Christmases ago. Unlike cell phones, I can’t say I have many evocative memories of video games except that I strongly associate the smell of Febreeze to Zelda: Ocarina of Time and the Powerglove never fucking worked. Ever.

Video games were like novels, something I consumed alone. Something you might talk about with friends but never experienced communally. Video games never offered me an entrance to a community. That was always something that computers and their attendant culture provided. I never called myself a “hacker” but I certainly loved the idea of controlling something so important and ubiquitous.

—

When my school was selected for a pilot program where each student got to rented a brand new iBook I got to work with some Apple sysadmins that told me what a prosumer was (I was a prosumer and I didn’t even know it!) and then showed me how to use Quicksilver. My 16 year-old-self looked at that Apple engineer like he was a priest of some religion I never knew I wanted to be a part of. It was exhilarating and that’s why I have a soft spot for people who say they have found community online. Sure, your community might be predicated on a constant global supply chain of rare earth metals and cheap energy but that feeling of belonging has the uncanny ability to make you justify nearly anything.

Which is not to say I was part of some marginalized group. Far from it. Instead I was experiencing the boundless joy that comes with that marginal increase in social acceptance. The world was made for me, and yet it took that little extra interest in a Unix based operating system that made me feel like I really belonged. Then came all the toys marketed and designed just for someone with my life experiences. It was exciting to have this kind of cultural cache. This distinction and fluency that opened doors both literal and figurative. I could get county level science fair awards just for building a robotic arm from a kit that I got for Hanukkah. It was socially acceptable to love lego well into my teens thanks to the first generation Mindstorms kit. I wasn’t playing with toys, I was training for a job at GE. So much of society insulates young white men from seeing just how incompatible the world is for just about everyone else. I try to hold onto these memories of high school belonging as a reminder of just how enticing and comforting white supremacy really can be. Which is not to say I was a white supremacist but I certainly loved, participated in, and defending a white supremacist status quo. When so much of the world is alienating, you’ll latch onto and defend even the most imperfect system that gives you that sense of belonging. his dynamic is just one of the many ways that imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy divides us against our collective best interests.

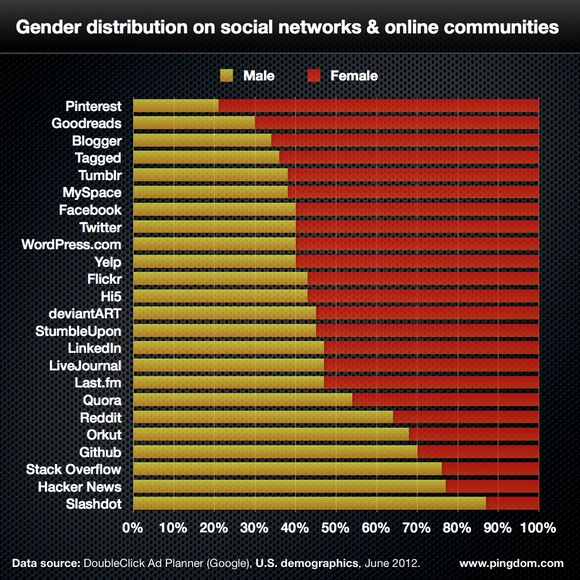

I haven’t even gotten to my first social media experiences. I mentioned Live Journal and AIM, but for some reason I associate the thrill of getting my college email address so I could sign up for Facebook with something totally different than my cell phones or that IBM computer. I was an early adopter of Twitter (2007) and I’ve been on Tumblr long enough that I remember seriously using Posterous instead. None of these experiences seem connected to the rest of this story except that they all happened on the first computer I called my own: a Powerbook G4. Perhaps everything that happened on and through that computer is best left for a totally different kind of essay.

Shapin and Schaffer catalogued this separation in their well-known book

Shapin and Schaffer catalogued this separation in their well-known book