The internet has been saturated with Trump memes. Some times they are hilarious, some times they are hurtful. Some times they bring relief, some times they are agonizing. This post is a product of my observations and archive of Trump memes and their evolving power from “subversive frivolity” to “normativity”. I demonstrate how Trump memes have transited along a continuum as: attention fodder, subversive frivolity, the new normal, and popular culture.

Screengrabs with the black header were archived from the mobile app version of 9gag on 8 November 2016, around 0001hrs, GMT+8 time. They include all the posts tagged “Trump”, with the earliest backdating to 14 weeks. There were 141 original memes in total but a handful have been omitted from this post. Screengrabs without the black header were archived from various news sites and social media throughout the Election season.

*

1) Trump as attention fodder

Trump is a one-man meme machine. The words that come out of his body are priceless attention fodder, and early screengrabs of his quotes on social media disseminated shock and disbelief. As a regular user of 9gag, new batches of posts each day seemed to compete for the “most shocking quote” as a means to garner up-votes and encourage high comment rates.

Although these memes circulated widely on social media, the circuit of Trump shock was supported, escalated, and institutionalized by mainstream media outlets that pursued string after string of sensational headlines and free publicity in the name of profits. Big profits.

Trump’s racist rhetoric spurned a meme ecology that increasingly distanced his hate speech from his celebrity persona, as humour and internerspeak cushioned viewers from the realities of his bigotry.

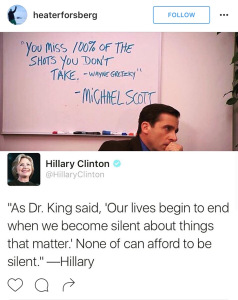

As part of my research on internet celebrity, I closely follow dozens of Influencers on a daily basis, and hundreds more monthly. Leading up to voting day, many Influencers from around the world began to partake in Trump memes as content fodder. This was in a bid to “join in the fun” in mocking Trump, using current events to relate to followers and maintain their relevance amidst the displacement of internet attention towards the US Presidential Elections. It was clear from empty melodramatic prose that many Influencers had little to no clue about Trump’s disastrous ethic and damaging policies, instead focusing on airy-fairy vague Instagram quote posts, Twitter quips, and Facebook status updates calling for no hate and hippie peace and love and flowers. I recognize and acknowledge that a strong command of the attention economy and the ability to re-narrate and redirect current issues to one’s self-brand is a crucial and learned strategy in the Influencer industry, but these appropriations of the Trump narrative fostered accessibility, a sense of acceptance, and an artificial sense of distance between the internet frivolity of meme-makers and the lived realities of voters in a post-Trump USA.

*

2) Trump as subversive frivolity

In April this year, I published a paper on the ways in which Influencers use selfies as a form of “subversive frivolity”. In it, I demonstrated how the continuous disregard for selfies as merely frivolous objects not to be taken seriously enabled Influencers to use them as artifacts, tools, and weapons to improve their self-branding, dispel bad press, and increase their commercial value.

I defined subversive frivolity as the under-visibilized and under-estimated generative power of an object or practice arising from its (populist) discursive framing as marginal, inconsequential, and unproductive.

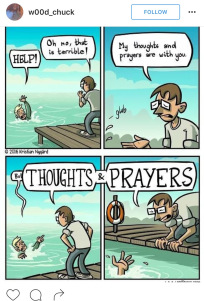

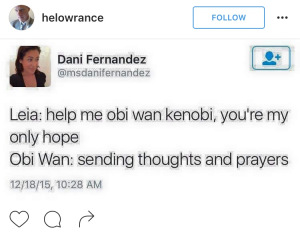

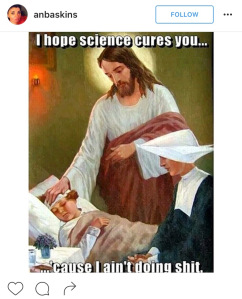

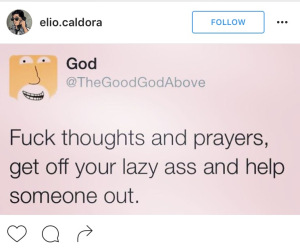

A similar process has occurred in our public discourse on Trump, in which our continuous production of and exposure to Trump memes has desensitized us from the real impact of his deadly proclamations and proposed policies. In other words, by boxing Trump and his harmful rhetoric into the usually whimsical vehicle of internet memes, the salience of his politic is diluted and parsed as mere frivolity to be traded and circulated as humour currency. It doesn’t help that we often Other him as a “crazy” person and undervalue his potential impact. It is our rehearsed internet meme literacies that have cultivated a blindspot to the insidious power of subversive frivolity lurking within Trump memes.

We caricature Trump with Photoshop skills or artistic sensibilities.

We mock his signature hairdo.

We pun his name.

In the process of meme-ing Trump as The Face, The Hair, The Name, we water away the discourse of Trump the Presidential Candidate, and now President Elect. While I acknowledge the potential of memes as a discursive practice of resistance, agentic mode of aggressive humour, and penetrative weapon of vernacular discourse, the steady current of Trump memes has surely anesthetized at least some of us to his vile politic.

*

3) Trump as the new normal

So almost all the poll projections for the US Presidential Elections were wrong. Very very wrong. And the moment Trump became President Elect, media outlets made the natural, seamless, and unapologetic transition into profiling the “new first family“. There are many of such articles that are now converting the once sensational and vitriolic discourse around Trump into your everyday, regular, unassuming press news, baked fresh every morning; but I note that Trump’s older daughter, Ivanka Trump, is fast becoming the media darling who is softening her father’s image, using her charisma to better the Trump family’s public reception, and probably executing some of his policies in time to come.

For instance, see People Magazine gushing over 27 photos of her “way too cute” family, The Straits Times commending her 5yo daughter for “win[ning] hearts of Chinese netizens” by reciting Chinese poetry, and The Guardian applauding her “thoughtful, composed and savvy” public persona.

Trump memes are also culprits of this normalizing discourse. Many “Hillary or Trump” memes imply a nonchalance and indifference between the two Presidential Candidates, as if both would have been equally “bad” outcomes.

Trump’s contentious foreign policies has also birthed a new string of diplomacy meme humour. Several versions of such diplomacy memes compare Trump to controversial past and current world leaders, including Hitler, Stalin, Lenin, Putin, and Kim. The aesthetic of these memes seem to welcome Trump to the Old Boys’ Club of dictators and fascists, as equal parts criticism and a badge of honour. In other words, Trump is lauded as “just another one of those bad boys” on the world stage. The cognizance of his new position as President Elect of one of the most, if not the most, influential countries in the world seems to be secondary.

*

4) Trump as popular culture

Prior to his foray into politics, Trump, the billionaire businessman and media mogul, made frequent appearances on television and cinema. Since running for the Candidacy, he has become a regular fixture in popular culture through internet memes, viral songs, merchandise, and art.

In fact, a quick search on community art commerce platform, society6.com, reveals streams and streams of unofficial Trump paraphernalia, juxtaposed against his official Election gear. I wonder how many folks are unironically buying Trump wear off artisanal commerce sites in the belief that they are resisting, rebelling, or revolting.

On this site and others, a string of dedicated artists have started shops specifically hawking Trump wear. The ambiguous aesthetic makes it difficult to ascertain if these products and art are meant to signify parody consumption as a subversive statement, or just plain idol worship.

*

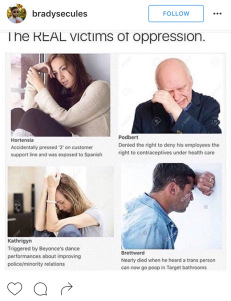

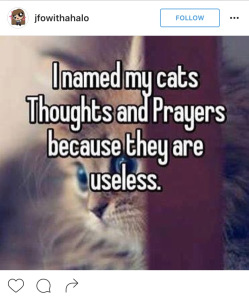

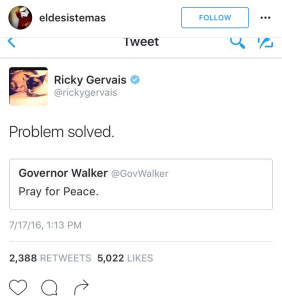

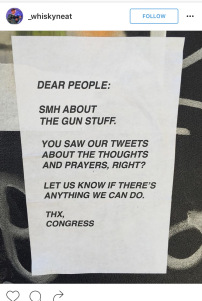

So, judging by their incredible virality, Trump memes have been enjoyable internet fodder for many people. But for all the potential resistance work, intellectual critique, and activism that such viral memes hold, different genres of memes may compete and be counter-productive for different fragments of people. The memes slut-shaming Melania and Ivanka Trump are one example of misplaced anti-Trump sentiment. Misogyny is never excusable.

Similarly, memes of lived realities of minority groups targeted under Trump’s proposed policies accumulated hundreds of thousands of upvotes and likes and retweets and reblogs. They may serve as commentary of reactions from the ground, but also have the potential to bring distress to targeted peoples who are still trying to make sense of their new precarity.

What’s next in the Trump meme ecology? I see your Biden/Obama memes. I see them from BBC, Buzzfeed, CNN, Harpers Bazaar, News.com.au, Observer, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Telegraph, The Washington Post, among others. And there is nothing wrong with such humour per se. In fact, scholars have studied such practices as “irony as protest“, “tactical frivolity“, and “pop polyvocality” among other current research on digital media. But remember that some of these very same news outlets were the ones who took you on their sensationalist-to-normative whirlpool of Trump discourse, and with the Biden/Obama memes, they are still making revenue off you, as you consume their bite sized meme humour as panacea to the President Elect Trump they aided to success.

*

See also:

1) Singaporeans react to Donald Trump

2) Things a Singaporean appreciates about the US Presidential Elections

3) Global politics is micropolitics

4) Parochial anxiety

Dr Crystal Abidin is an anthropologist and ethnographer who studies Influencers and internet celebrity. Reach her at wishcrys.com and @wishcrys.