What do you get when you cross professor Carolyn Liebler from the University of Minnesota Sociology Department, Census data, and issues of identity? An immigration reform segment on the Colbert Report.

What do you get when you cross professor Carolyn Liebler from the University of Minnesota Sociology Department, Census data, and issues of identity? An immigration reform segment on the Colbert Report.

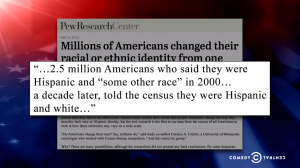

Recently, the Comedy Central satirist pulled a quote from Liebler’s research saying:

2.5 million Americans who said they were Hispanic and “some other race” in 2000… a decade later, told the census they were Hispanic and white.

Of course, Colbert went on to explain his version of these findings: that Hispanics were voluntarily becoming white. Colbert points out that white people live in the best neighborhoods and get the best jobs, among other things. With that logic, why not “choose” to be white?

From a sociological perspective, he might have something there. Issues of identity are fluid. Looking at such a large change in the Census data provokes questions as to why this variation in identity exists. In an interview with NPR, Liebler drew a parallel to her work studying Native American identity:

Between 1960 and 1970, nearly a half-million more Americans identified themselves as Native American—a number that was too large to be explained by mere population growth, she said. Something else had to explain it.

In Colbert’s telling, ethno-racial identification shifts will be key in Republican victories in upcoming elections—the more people who identify as “white,” the more votes the GOP will garner.

Check out the clip here! For more on race and ethnicity among Hispanic Americans, see Wendy Roth’s “Creating a ‘Latino’ Race.”