Reposted from Psychology Today

Enough already. Aziz Ansari is not a rapist nor necessarily even a liar. Nor is “Grace” the woman who had the worst night of her life either a victim or a vixen. They are both casualties of our gender structure. Let me explain.

Most people think that gender is an identity, some authentic knowledge about the self. But identity is really only a small part of how gender structures our lives, our society. If we want to understand what happens in heterosexual hook ups, we have to understand the gendered meanings of the hook up culture. Every society has an economic structure, and so too every society, including ours, has a gender structure which has implications for our personalities, our expectations of others, our ideology about what should be, and our acceptance (or rejection) of sexual inequality.

Gender is part of how we define ourselves. Most of us are still raised to be good little boys and girls. Good boys don’t cry, but they do get notches in their belts from peers for objectifying women, and pursing them sexually. Girls are told they can be anything they want to be, you go girl, but when it comes to their bodies, they should accessorize fashionably and please men. Girls may ‘rule’ but they are still expected to be nice when doing so. And of course, women remain the sexual gatekeepers, deciding when boys get that notch on their belt. There is strong evidence that gender gets inside us, that socialization helps create feminine girls and masculine boys. Socialization shapes how we behave. Girls like “Grace” are taught to be nice, to be subtle and polite in their rejection of men, to give off non-verbal cues rather than causing a scene or using a four letter word. Boys learn that they are entitled to get what they want, but only if they go for it. They are taught to tackle, to score. No one has to do anything to encourage women and men to behave this was as adults, gender is internalized into who we are.

But that’s only the beginning of the explanation for the he said/she said sexual drama, the overt and covert coercion that the #MeToo movement has illuminated. Gender isn’t only how femininity cripples women, nor how toxic masculinity empowers men. It is also the expectations we take for granted, when we interact, and the unconscious scripts that have problematic outcomes, including during heterosexual casual sex. Erotic imagination in male-centric. Take this date in question. The woman spent time discussing an outfit with friends; she is attempting to appear desirable. Aziz controlled the very existence of the encounter (doing the asking) and orchestrated it (choosing the wine, the restaurant, and paying the bill). Without conscious reflections, cultural expectations and scripts are followed: the man’s agency creates the date, the man is the sexual aggressor, the woman sought after, and paid for. This is still the lay of the land in 2018, the script that “Grace” describes of her evening with Aziz. Has he bought just dinner, or the expectation of sexual intercourse?

What men and women expect from one another is not just a part of their relationship, but part of a societal story about sexual desire, desirability, nudity, and power. Does a woman who goes to a man’s home, undresses, and acquiesces to receiving oral sex providing non-verbal cues that she intends to have penetrative sex? No woman should ever be pressured into any kind of sex. And yet, the narrative of heterosexual seduction at the core of our romantic myths includes a reluctant woman won over by a persistent suitor. Pair that with the material wealth and status advantage most men have over their dates (and the super star quality of this particular man) and you get an explosive potion for coercion, under the cover of erotic play. And a prescription for male privilege: research shows clearly that men are far more likely to orgasm in a hook up then are their dates. Our heterosexual script has desirable women seduced by powerful, sexual men. If you disagree, explain how the movie 50 shades of grey made such a fortune.

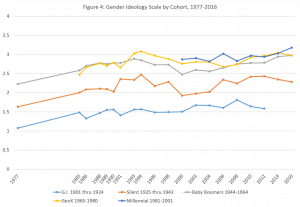

Sexual coercion, non-consensual sex, is always wrong. Any form of assault is a crime. And still, there are shades of grey, beyond 50, when women and men are confused by a changing gender structure. In today’s world everything is in flux. As my forthcoming book suggests, some young adults totally reject their socialization as feminine male-pleasing women and chauvinistic men and instead try to incorporate both masculinity and femininity into their personalities. Others fully endorse a world where men are expected to be the pursuers of feminine woman. Our gender structure is changing, but unevenly, and without any clear guidelines. When it comes to casual hetero sex, gender is embedded in our own desires, our expectations for partners, and acceptance of cultural norms, and power differentials. And desire, expectations of acceptable norms may contradict one another.

Perhaps half way thru the encounter a woman decides she’s had enough, and doesn’t care any more about being desirable for a powerful man she does not desire. She can, and should, dress and walk away. But her socialized internal gendered self, however, may scream: be nice. And so she politely tries to indicate non-verbally, she’s not into it. He should get the hint. But then again, his training for masculinity, toxic as it may have been, screams keep trying, that she’ll get into it eventually, if he is just seductive and persistent enough. She feels pressured, he becomes a predator. Neither plans on the transformation of a date into a #MeToo moment.

The only way out is to smash the gender structure entirely. Let’s stop arguing about whether she should have been more assertive (less girly) and walked away earlier, or whether he should have understood her signals. It’s both/and not either/or. Let’s stop raising masculine boys and feminine girls. Stop teaching girls to be nice, even to men who pressure them. Stop raising boys who feel entitled to sex even if their partner is not enthusiastic. Let’s raise boys to have empathy for others, to cry when they feel pain. Let’s raise good people, not women and men. We must shatter gender stereotypes, including those about dating and sex. All people experience desire and arousal, seek orgasms, and love. No one should wait to be desired, nor be expected to give more then they get, whether sex or love. Can this happen when men still hold the power outside of the bedroom? Probably not. The male privilege deeply embedded in our gender structure must end everywhere: how we raise our children, what we expect from one another, and the distribution of power and prestige at work, in government, in Hollywood, including between the sheets.

Barbara J. Risman is a Distinguished Professor of Sociology in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also a Senior Scholar at the Council on Contemporary Families.

employed are

employed are  The term “millennial,” according to Frank Furstenberg, is an

The term “millennial,” according to Frank Furstenberg, is an