CORRECTION: The original version of this post had a major error – the second trend was coded wrong, showing percent married instead of percent single! I’ve correct it, and apologize for the error.

Earlier this month there was a funny segment on Fox and Friends where they took seriously a fake social media campaign, supposedly led by feminists, to end Father’s Day. “More of this nasty feminist rhetoric,” and The Princeton Mom (Susan Patton). “They’re not just interested in ending Father’s Day, they’re interested in ending men.”

Then Tucker Carlson jumped in to ask, “Why is it good for women? I mean, there’s a reason there are more women living in poverty now than at any time in my lifetime, it’s because there are fewer married women. I mean, when you crush men, you hurt women.”

His comment is doubly twisted. First, it supposes that the historical rise of single mothers is the result of feminists crushing men (thanks, Hanna Rosin). The decline in marriage is related to the falling economic fortunes of men, especially relative to women, but I don’t think you can lay much of that at the feet of feminists.

Second, are there really more women in poverty now because of single motherhood? Yes and no. Here are three trends (all based on civilian non-institutionalized women ages 18+, from the Current Population Survey):

1. Poverty is rising among all women (but still hasn’t reached 1990s levels)

Although the proportion of children born to women who aren’t married has increased – doubling in the past three decades – that doesn’t tell the whole poverty story. Because women’s employment opportunities increased during that time (and fertility rates fell), women’s poverty rates are lower now than they were in the 1980s and 1990s peaks.

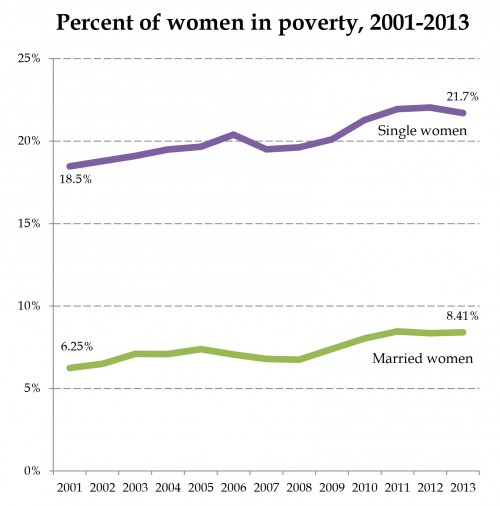

Zooming in on the period from the low poverty point in 2001, you can see that the recent increase in poverty has affected single and married women, and the proportional increase is actually twice as great for married women (more than a one-third increase).

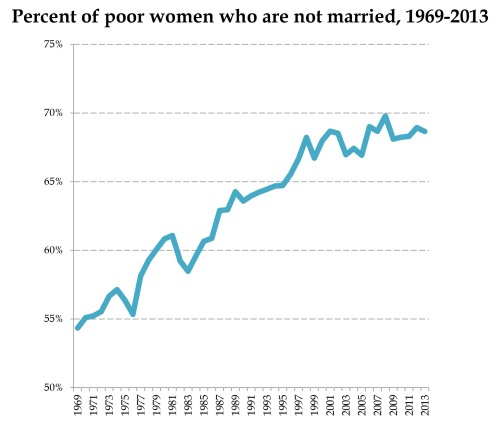

2. The percentage of poor women who are not married has risen (corrected trend!)

Nevertheless, the percentage of poor women who are not married has risen. During the 2000s recession, the percentage of poor women who are married hit an all-time low of 30%. Over the last four decades, as marriage rates have fallen, women’s poverty has become more concentrated among unmarried women. Single women have much higher poverty rates than married women, and the vast majority of poor women are not married. However, in the last 15 years, as single motherhood has become more common, the percentage of poor women who are not married has been basically flat.

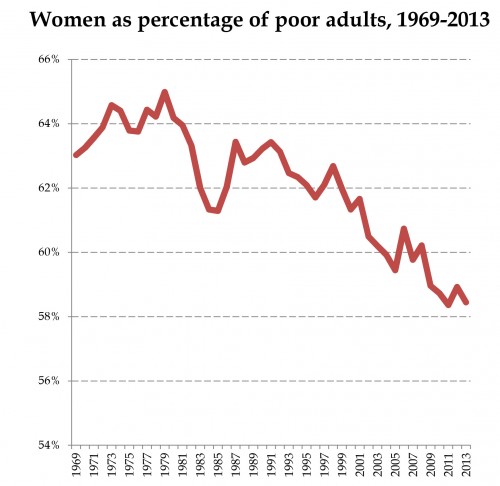

3. The percentage of poor people who are women is falling

Diane Pearce wrote, “The Feminization of Poverty: Women, Work, and Welfare” in 1978, as single motherhood was increasing and women’s wages relative to men’s appeared flat. As the proportion of poor adults that were women approached two-thirds, this shocking term caught on. However, since then — as women’s earnings increased and wages fell for many men — that proportion has fallen to 58%.

These facts are not the whole story of poverty in the U.S. But they should be enough to stop the politically convenient simplification repeated by the Tucker Carlsons of our time. The problem of poverty is not a problem of women’s failure to marry.

Cross-posted on Families As They Really Are