Assortative mating – the tendency of people to marry those similar to themselves – has become a popular explanation for increased economic inequality across American families (see the NYT, the Economist, or the NYT Upshot).

The idea is that if people are increasingly matching with partners who have similar economic prospects, families will be increasingly divided between those who pool two large paychecks and those who pool two small paychecks. More assortative mating increases spouses’ economic similarity, which in turn increases inequality.

Our research, however, shows that assortative mating has played a minor role in the increase of spouses’ economic similarity and its impact on inequality. More important than changes in whom people marry are changes in what happens after they marry. In particular, the well-known and dramatic increase in wives’ employment within marriage are responsible for the bulk of the effects of increased spousal economic resemblance on inequality.

That is, the rise of spouses’ economic similarity increased inequality not because there are more “power couples” who match with one another, but because both wives and husbands today are more likely to realize their economic potential during marriage, whereas in the past only one (usually the man) would do so.

Explaining increased spousal economic resemblance

The appeal of assortative mating as an explanation for spousal economic resemblance and inequality is based on well-known social and economic shifts. Declines in gender inequality in education and the workplace mean that women’s socioeconomic standing is increasingly similar to men’s. For instance, it is easier for a man with a PhD to match with a female PhD today than in 1970. These compositional shifts alone may drive increases in assortative mating.

In addition, men’s and women’s preferences for partners have shifted towards valuing similarities rather than differences, rising income gaps between college and non-college workers imply that individuals can lose more by “marrying down”, and growing residential segregation by income restricts opportunities to meet partners outside ones’ own income bracket.

This focus on assortative mating, however, has tended to overlook what happens after couples match, that is, how families organize their economic life: who is bringing money in, how much, who is dropping out of the labor force, and for how long? Overlooking these questions is surprising given the magnitude of changes in the economic organization of families.

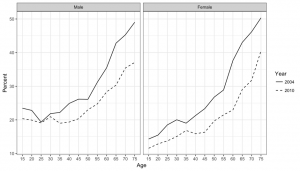

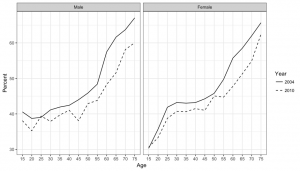

The rise of wives’ and mothers’ employment since the 1960s shifted the modal division of paid labor from breadwinner/homemaker to dual-earner. As women are participating in the labor force for more time than in the past, their earnings are closer to men’s for more of their married lives. These shifts have the potential to increase the economic similarity of spouses, even without any increase in assortative mating.

The importance of these changes suggests that the rise of spouses’ economic resemblance could largely be a function of what happens after marriage, not the sorting process that happens before marriage.

And this is exactly what our study finds.

Contrary to what has often been assumed, we show that the contribution of assortative mating to the inequality-generating effects of spouses’ economic similarity is very small. This is because there is no evidence that economic assortative mating has substantially increased in the last four decades; newlyweds are not more economically similar today than they were in the 1970s.

Instead, couples have become more economically similar during marriage, due to the increase in wives’ labor force participation. This shift in couples’ division of paid labor is the driving force behind the rise of spouses’ economic similarity and its impact on inequality.

Implications

We underscore two implications of this finding. One is that more attention should be paid to the effects of the economic organization of families on inequality. There is a lot more to be unpacked about how and why shifts in the division of paid labor during marriage can increase inequality. For instance, is it about “power couples” being more able to sustain the dual-earner model during parenthood? Is it because those with more education tend to have fewer children than those with less education?

Another implication is that it is necessary to follow couples through their married lives to distinguish what family-level processes contribute to inequality. Researchers often measure assortative mating using averages across all couples in the population, thereby lumping together variation that exists at the time of marriage and variation that evolves during marriage. This might not be problematic for measures that do not change much over individuals’ lives, like education or race, but it is clearly misleading for measures that vary systematically over time, such as labor supply or earnings.

In sum, the division of paid labor within families is key to understanding the future of inequality across American families. Assortative mating on earnings has been the focus of prior work, but has played only a small role shaping the economic resemblance of spouses and its contribution to inequality.

Pilar Gonalons-Pons is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. Christine Schwartz is a Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This article summarizes findings from “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” in Demography. For a free, pre-publication version of the article, click here. This post was published on 10/17/17 at Work in Progress.

In light of

In light of