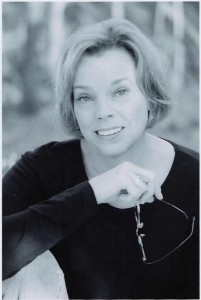

Linda Nielsen is a Council on Contemporary Families Expert, as well as a professor of Educational and Adolescent Psychology at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. Most of Nielsen’s research centers around the relationship between fathers and daughters. Nielsen’s research gained national attention when Pantene—the shampoo brand—reached out to her in hopes of creating a Super Bowl ad that was inspired by her research and centered around the importance of father-daughter relationships. Nielsen answered a few questions for us about her research, her own family, and any advice that she has:

Linda Nielsen is a Council on Contemporary Families Expert, as well as a professor of Educational and Adolescent Psychology at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. Most of Nielsen’s research centers around the relationship between fathers and daughters. Nielsen’s research gained national attention when Pantene—the shampoo brand—reached out to her in hopes of creating a Super Bowl ad that was inspired by her research and centered around the importance of father-daughter relationships. Nielsen answered a few questions for us about her research, her own family, and any advice that she has:

Q: First, a challenge: what’s one single thing you “know” with certainty, after years of research into modern families?

LN: After writing books and articles about fathers and daughters for nearly three decades, the one single thing I know about father-daughter relationships is that most fathers and daughters would both like to have a more communicative, more comfortable, more personal relationship with one another. Both would like to spend more one on one time together without other family members involved – especially during the daughter’s teenage years when society generally discourages anything more than dad being involved in his daughters’ athletic or academic life – or being her banking machine.

Q: What does your family–both family-of-origin and family-of-choice–look like, and how does that fit with what you know about American families today? Are there points of dissonance? more...

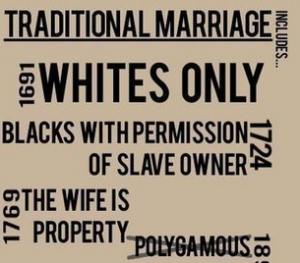

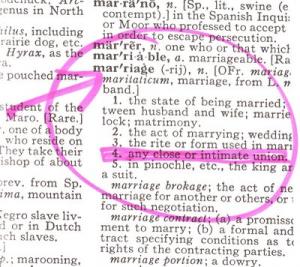

It is challenging to untangle contemporary definitions of marriage from definitions of wife and husband. Wife is a noun, defined in relation to another. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, wife means “the woman someone is married to.” Wives often take on adjectives such as military wife, political wife, housewife, and so on.

It is challenging to untangle contemporary definitions of marriage from definitions of wife and husband. Wife is a noun, defined in relation to another. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, wife means “the woman someone is married to.” Wives often take on adjectives such as military wife, political wife, housewife, and so on.