Nell Frizzell is a journalist and author who writes about gender, culture, art, and politics. She has written for The Guardian, VICE, The Telegraph, Elle, Grazia, The Pool, The Observer, Buzzfeed, Refinery29, Red and Time Out. She is also a Vogue columnist, writing about motherhood under the title Bringing Up Baby. Here, I ask her about her forthcoming book The Panic Years: Dates, Doubts, and the Mother of All Decisions. You can find out more about Nell at nellfrizzell.com,

Nell Frizzell is a journalist and author who writes about gender, culture, art, and politics. She has written for The Guardian, VICE, The Telegraph, Elle, Grazia, The Pool, The Observer, Buzzfeed, Refinery29, Red and Time Out. She is also a Vogue columnist, writing about motherhood under the title Bringing Up Baby. Here, I ask her about her forthcoming book The Panic Years: Dates, Doubts, and the Mother of All Decisions. You can find out more about Nell at nellfrizzell.com,

KM: Beyond the biological component, are there other ways that you feel like women uniquely feel the pressure from society to have a baby by a certain time and why do you think this is? What do you think society and public policy – and perhaps the men in women’s lives – can do to ease the burden of this pressure and support women both while they are deciding whether or not to have a baby and then once they actually do start child-rearing?

NF: I am amazed by how ubiquitous the expectation that girls will have babies still is today. My 16-year-old sister has a list of her favorite baby names saved onto her phone. I wonder how many boys her age are ever asked what they want to call their children? It’s there in the way we talk about female ambition (as something that will run alongside family life), the way we encourage girls to practice caring in a play setting (playing with dolls, cooking, putting toys to bed in mini cots, pushing prams, etc.), the way we ask the most fundamental and private questions as though they were breezy small talk “So, do you want a baby?” Of course all this could and should apply to people who identify as men, but I fear it is not. We still allow, even encourage, men to consider having children as something peripheral and potential, rather than a reality that they could plan for, hope for or prevent right now, in their life.

There is also the very strong cultural narrative of the ‘geriatric mother’ and the ‘cliff edge’ of fertility after 35. The truth is of course much more nuanced, much more specific to each individual’s biology and lifestyle and therefore, hopefully, less scary. We are very happy to warn women that their fertility is finite without really mentioning the correlated decrease in fertility and rise in congenital illness, quality of sperm, etc. in men.

With regards to policy, well here’s a question. Firstly, let’s actually enact the demands made at the first Women’s Liberation Conference in 1970 at Ruskin College (it’s the anniversary this year!)

- Equal pay

- Equal opportunity

- Contraception and abortion on demand

- Free 24 hour nurseries

That way, the decision to have a baby is a far less polarizing one: it will have a less damaging impact on your career, it will cost you less materially, financially, socially and personally, it will be easier to avoid getting pregnant if you’re not ready or not in the right circumstances to raise a child, it will not affect your opportunities to reenter the public world after you’ve given birth.

I would love to see free childcare for all children under 5. It doesn’t just make sense on a humanitarian level – literally making the population healthier, happier and more likely to contribute to a well-adjusted society – but it makes economic sense not to have half the workforce taken away from their job in order to look after children OR almost half the workforce’s entire income going directly to someone else looking after your children.

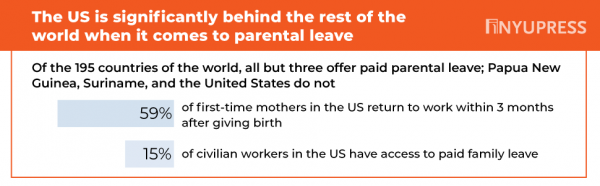

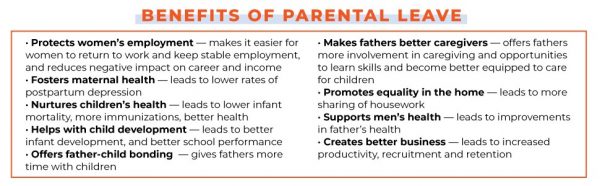

Better paid parental leave – for the same reasons as above. A father and mother who have the opportunity to bond with and nurture their child are far more likely to treat that job with the care and attention it deserves; their child is going to benefit from a caring environment, they will be better equipped to navigate interpersonal relationships, if their parent chooses to breastfeed their physical health will be better – the list goes on and on.

I would also like men to just think about having babies. Not to push it to one side while they concentrate on ‘the big things’ i.e. studying, work, sport, friendships, sex, money. But to have it as a question, something to prepare for, or make contingencies for from the moment they are sexually active. Let them take on the burden of contraception, particularly if they don’t want children. Side effect free, hormone-free male contraception and, until that is on the market, let’s talk again about vasectomies. If you are a man who is certain you never want a child or don’t want any more children than enact that decision in your body – have a vasectomy – don’t instead expect women to spend their lives adjusting their bodies to conform to your desire.

KM: You often leverage data and statistics in support of the topics in your articles – from a sociological point of view, in your experiences from thinking about becoming a mother to actually doing so, do you feel there are areas of research in this field that need further exploration to understand this process better?

NF: Yes. The cost of childcare should be much much more widely understood than it is now. I had no idea, until I had a child, that I couldn’t afford to have a child. Also, if more people understood that the average cost of childcare for one child, under 2 in the UK, for someone on the UK average wage, is 43% of their income, hopefully they would agitate to change that before they have a child and are already, well, trapped.

The decrease in male fertility over time. I think we need to start talking much more frankly and openly about male fertility – stop putting the blame, the decision and the burden all on women’s bodies.

Finally, please god could someone do some research – a LOT of research – into the effect of hormonal contraception (actually, hell, all contraception) on female mental health. We know that the pill is literally killing women – driving them into depression and suicide. We all know anecdotally the horrendous side effects of so much contraception. And yet there seems to be so little scientific and sociological research into it.

KM: What made you decide to write a book on this topic? What is the one lesson or advice or insight you want readers to take away?

NF: Partly, honestly, because I’d had a baby I simply couldn’t work in the way I used to as a freelance journalist. I couldn’t pitch three ideas a day while also surviving on 5 hours broken sleep and under 24-hour care of a baby. A book would give me the opportunity to work on one project over the course of months, rather than having to turn around copy every day within hours just to pay the bills.

On a more creative level, I also wanted to write this book because, having lived through The Panic Years and going through my own Flux, I knew what a bewildering, devastating, disorienting and paralyzing time it could be. I wanted to give this thing a name so women everywhere could see their own experience as part of a social and biological phenomenon, rather than a personal crisis. I wanted friends, sisters, colleagues to have a short hand with each other to explain what they were going through “Oh, I think she’s hit her Flux, so maybe we should go over with a lasagna”.

I wanted us to see the ways our gender conditioning, work culture, sexual attitudes and social care were still oppressing us. I wanted to point out the underlying injustice that still exists around fertility, childrearing and contraception.

Also, more privately and personally, I wanted my partner, friends and family to understand what I’d gone through and how it had felt.

Kim McErlean is a Ph.D. student studying Sociology, with an interest in Family Demography, at the University of Texas at Austin.