Reposted from the University of Texas at Austin Population Research Center

While it is well-established that marriage benefits physical and emotional well-being, it is not marital status alone that matters but also marital quality. Substantial evidence demonstrates that marital strain increases psychological distress for married people. Most of this evidence is based exclusively on people’s own reports of the strain they feel in their marriages, referred to by researchers as “self-reported marital strain.” However, most research has not considered how a spouse’s perceptions and feelings about the marriage, known as “spouse-reported marital strain,” may also contribute to an individual’s distress.

Obtaining information from spouses is important because even if an individual is generally happy with the marriage, his or her spouse might be unhappy. The individual can then pick up on and be negatively affected by the spouse’s unhappiness. Dyadic data, which obtains appraisals from both spouses, may therefore provide important insights into the association between marital strain and psychological distress.

Prior research, based almost exclusively on different-sex couples, also suggests that marital strain may lead to more psychological distress for women than for men. This gender difference has been theorized by some to be the result of women’s greater interpersonal connections, which may increase their awareness of and reactivity to relationship strain. Others argue that gendered power dynamics, in which women are seen as subordinate to men, explain this difference.

Same-sex couples typically adhere less strongly to gendered norms and expectations and are more egalitarian than different-sex couples. A gender-as-relational perspective – which argues that the way women and men enact gender differs depending on whether they are interacting with a woman or a man – would suggest that the relationship between self- and spouse-reported marital strain and psychological distress might operate differently for women and men in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual marriages.

Conducting research on different- and same-sex couples could shed light on competing theories of why women generally experience more distress as a result of marital strain. On the one hand, if women are more aware of interpersonal dynamics within marriage, they may be more susceptible than men to psychological distress as a result of marital strain regardless of whether they are in a different-sex or same-sex marriage. On the other hand, if women in different-sex marriages are more likely to be in relationships that reflect gendered power dynamics in which they are subordinate to men, they may be especially vulnerable to distress as a result of marital strain.

To examine whether and how self-reported marital strain and spouse-reported marital strain are associated with psychological distress and whether differences exist for women and men in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual marriages, we analyzed ten days of dyadic diary data from 756 U.S. women and men in midlife.

KEY FINDINGS

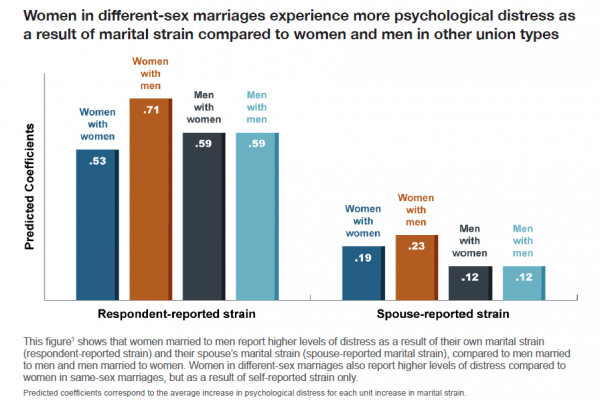

►►People who report higher levels of their own marital strain (“self-reported marital strain”) have more psychological distress. In addition, people whose spouses report higher levels of marital strain (“spouse- reported marital strain”), also experience more psychological distress.

►►However, there are notable gender differences in these relationships: women in different-sex marriages suffer more compared to women in same-sex marriages and men in same- and different-sex marriages. (See figure)

►►The association of self-reported marital strain with psychological distress is stronger for women in different-sex marriages compared to all other union types.

►►The association of spouse-reported marital strain with psychological distress is stronger for women in different-sex marriages when compared to men in same- and different-sex marriages.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Implications for research on marital dynamics and health

Research on marriage needs to consider the perspectives of both spouses when exploring linkages between marital dynamics and well-being. Data from both spouses is especially useful because it allows researchers to explore how perceptions, behaviors, and characteristics of each spouse may independently impact the health and well-being of either one or both spouses.

To fully capture the range of marital dynamics and their impact on health – especially for gender differences in these linkages – future studies should include same-sex couples as well as different-sex couples.

Research would benefit from taking a gender-as-relational approach to studying marital relationships. As this research clearly shows, it is not an individual’s gender but rather an individual’s gender in combination with his or her spouse’s gender that plays a key role in the link between marital strain and psychological distress, with women married to men showing a unique disadvantage compared to other union types. Thus, research must look beyond the individual to consider how gendered relational contexts shape processes of health and well-being.

Implications for mental health professionals

Clinicians would also benefit from considering the gendered relational contexts of marital relationships. In other words, counseling and other professional interactions with couples would be strengthened by thinking of the individual in combination with their spouse’s gender.

Indeed, when mental health clinicians move beyond an exclusive focus on the individual and expand their approach to also consider the gender of their patient’s spouse, they can better understand and thus provide better care to their patients across all marital contexts. This is especially vital for women in different-sex marriages. Given the higher rates of depression and anxiety for women, a focus on improving the marital experiences of women in different-sex marriages may help to reduce mental health disparities.

Study findings also point to the importance of considering how either spouse’s perceptions of marital strain and conflict can undermine the psychological well-being of both spouses. Thus, clinicians should make every effort to collect information about both the patients’ and spouses’ marital experiences.

Michael A. Garcia (michael.garcia@utexas.edu) is a PhD student in sociology and a graduate student trainee in the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin, and Debra Umberson is a professor of sociology and director of the Population Research Center, UT Austin who holds the Christine and Stanley E. Adams, Jr. Centennial Professorship in Liberal Arts.

This research was supported, in part, by Grant R21AG044585 from the National Institute on Aging (PI, Debra Umberson); Grant P2CHD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD); and Grant T32 HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by NICHD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.