A short interview with Stephanie Coontz by Virginia Rutter on a new CCF study.

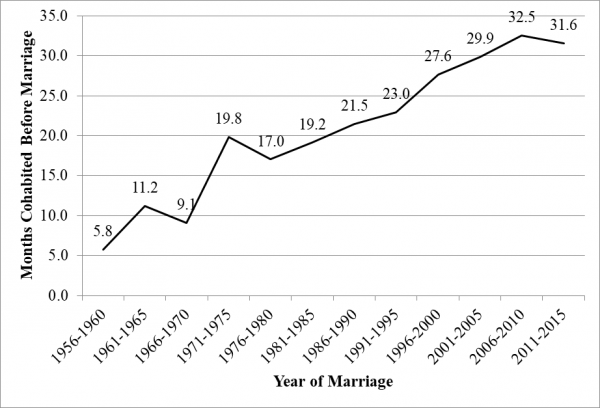

VR: You edited the new brief report on cohabitation trends from the Council on Contemporary Families. In it, Arielle Kuperberg reports that premarital cohabitation is more common—occurring before 70 percent of marriages. But what does this new research tell us about Americans’ intimate lives?

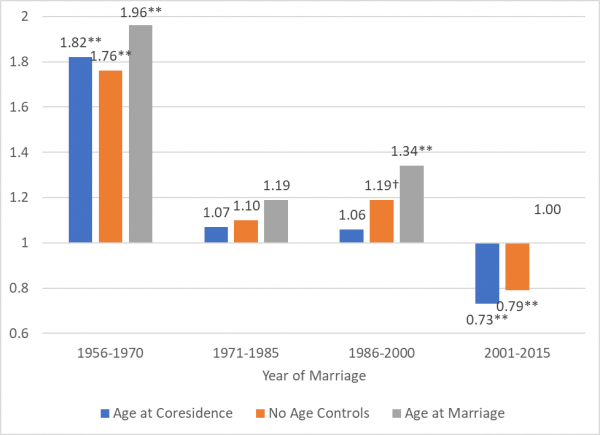

SC: First of all, it adds to our understanding of how quickly the norms and dynamics of personal relationships are changing. Until 1970, couples who cohabited before marriage were 82 percent more likely to divorce than those who married directly. That extra risk is now gone. Similarly, until the 1980s, marriages in which wives had more education than their husbands had a higher risk of divorce than other couples. But since 1990 that extra risk has also disappeared. Despite constant claims to the contrary, it is no longer true that marriages where the wife earns more than her husband are at higher risk of divorce. Finally, couples where the wife did most of the childcare and housework used to report better sex lives than couples with a more egalitarian division of labor. Now the opposite is true.

Within couple relationships there are many signs of growing equality. But that leads to a second contribution of the paper, which illustrates the growing inequality among couples on the basis of higher education, and in turn on their prospects for earning a family wage.

VR: Cohabitation looks like it is useful and valuable to many—as Kuperberg shows in the reversal of that out-of-date link between cohabitation and divorce. (See her awesome Figure 3 for a visual of the reversal!) But some people don’t want to cohabit. What do you think of Kuperberg’s findings about religion, escalating inequality, and access to “direct marrying”?

SC: Despite the widespread social acceptability of premarital cohabitation, a minority of Americans, especially those with strong religious beliefs, continue to disapprove of the practice and prefer to marry directly. Kuperberg highlights the painful dilemmas facing those who hold more traditional values but lack the resources to act on them. While two-thirds of religiously-observant women with a BA or higher did not cohabit before marriage, this was true of only 14 percent of equally observant women who did not attend college — and of just three percent of religiously-observant women without a high school diploma. As Kuperberg suggests, this is almost certainly not because of different values but of different options.

I agree that this gap likely reflects the difficulties that less-educated couples face in meeting the increasingly high economic bar for marriage. And it is especially troubling that the gap used to be just between the least-educated women and everyone else but is now greatest between the most-educated women and everyone else. The same escalating inequality between the most highly-educated Americans and others who work just as hard but are paid drastically less is also seen in rates of non-marriage and out-of-wedlock childbearing.

This divergence is likely to continue, given recent evidence that, as yet, the only group to have recovered fully from the Great Recession is people with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

VR: So what do you make of that? Growing equality within couples, and growing inequality between couples?

SC: For one thing, it means that much family instability results not from people’s different values or “culture” but from their inability to meet the high interpersonal and economic expectations of marriage that most Americans now embrace. I am thinking of the economically insecure people who move in together rapidly and then don’t move on to marriage, resulting in a lot of churning; the growing numbers of people who are not seen as marriageable by others due to poor job prospects or low wages (low-income men right now have the worst marriage prospects); youths who lack the kind of life opportunities that give them incentives and tools to defer childbearing.

For another thing, when people feel that they are being excluded from the American Dream, they often embrace short-term coping mechanisms or compensating behaviors that make their personal lives and relationships even more difficult. And with higher wage inequality, fewer work-family protections, and a weaker social safety net than other advanced industrial economies, the U.S. imposes exceptionally heavy penalties on people who become single parents or do not complete higher education, leading to lower rates of social mobility – and higher rates of personal problems. As I’ve written elsewhere, the long-standing American myth that individuals succeed purely on their own, on the basis of their personal “grit,” actually undermines people’s ability to establish families that can thrive.