Originally posted June 29, 2016

In early September 2015, Blanca Borrego, an undocumented Latina immigrant accompanied by her two daughters, arrived at a women’s health clinic in Texas for a routine gynecological exam. Sitting in the waiting room for nearly two hours, Blanca’s anxiety and impatience grew to the point where she almost walked out of the office. Eventually, Blanca was met by local law enforcement officials who escorted her out of the clinic in handcuffs for allegedly using a forged driver’s license during patient intake. Blanca’s eight-year-old daughter watched in tears while her mother was taken away and a deputy told Blanca’s eldest daughter that their mother would face deportation. Blanca remains in county jail on a $35,000 bond.

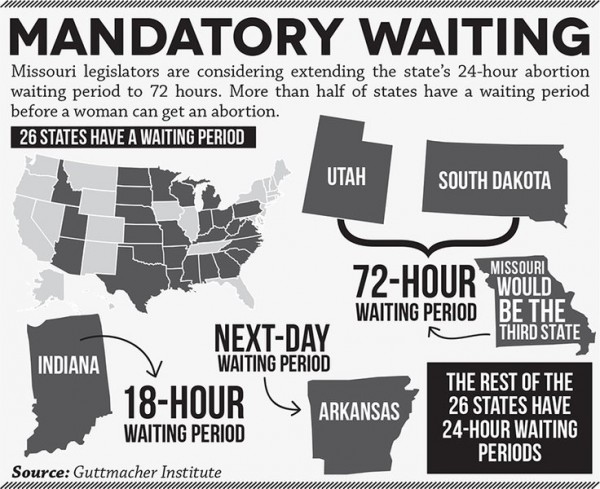

Scenarios like Blanca’s – highlighting the impact of race, class, and immigration status on reproductive rights – are not always brought to the fore. Although reproductive rights activists say they advocate for all women, difficulties faced by white, middle-class, heterosexual women get more attention than those experienced by women of color, immigrant or transgender women, or those with disabilities. However, a movement for reproductive justice has emerged by and for women of color that offers new possibilities to bring previously neglected issues to light. Key challenges include tackling the reproductive experiences of Latinas – and looking for ways to do more to address their needs in reproductive health care and policy.

Latina Realities

Understanding Latinas’ reproductive lives requires understanding how many forms of disadvantage intersect and create reinforcing disadvantages. more...

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.