For a long time, political talk at the “moderate middle” has focused on a common theme that goes something like this:

There is too much political polarization and conflict. It’s tearing us apart. People aren’t treating each other with compassion. We need to come together, set aside our differences, and really listen to each other.

I have heard countless versions of this argument in my personal life and in public forums. It is hard to disagree with them at first. Who can be against seeking common ground?

But as a political sociologist, I am also skeptical of this argument because we have good research showing how it keeps people and organizations from working through important disagreements. When we try to avoid conflict above all, we often end up avoiding politics altogether. It is easy to confuse common ground with occupied territory — social spaces where legitimate problems and grievances are ignored in the name of some kind of pleasant consensus.

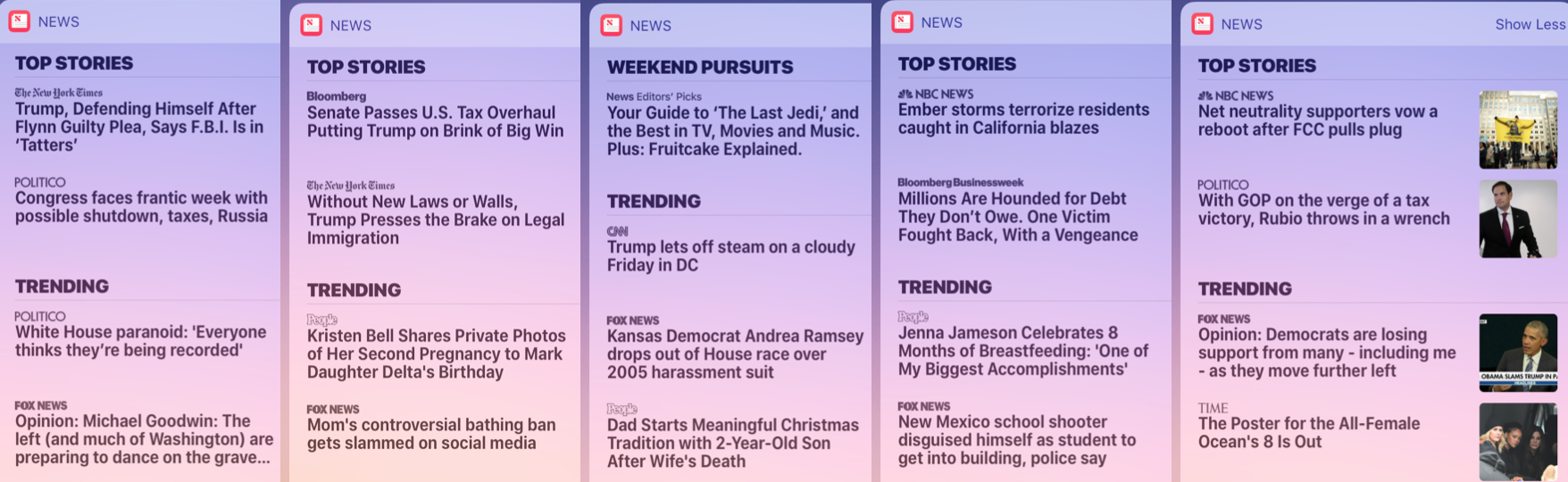

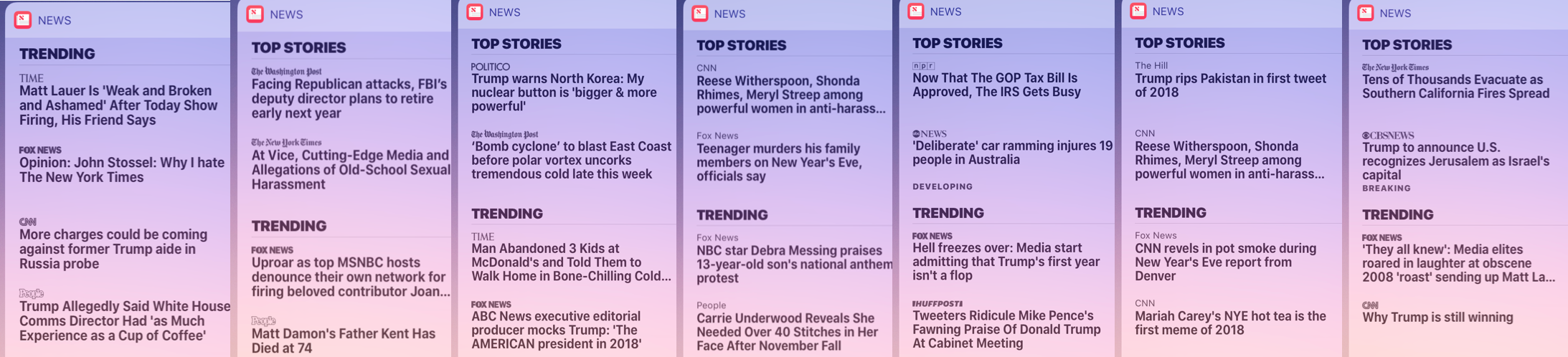

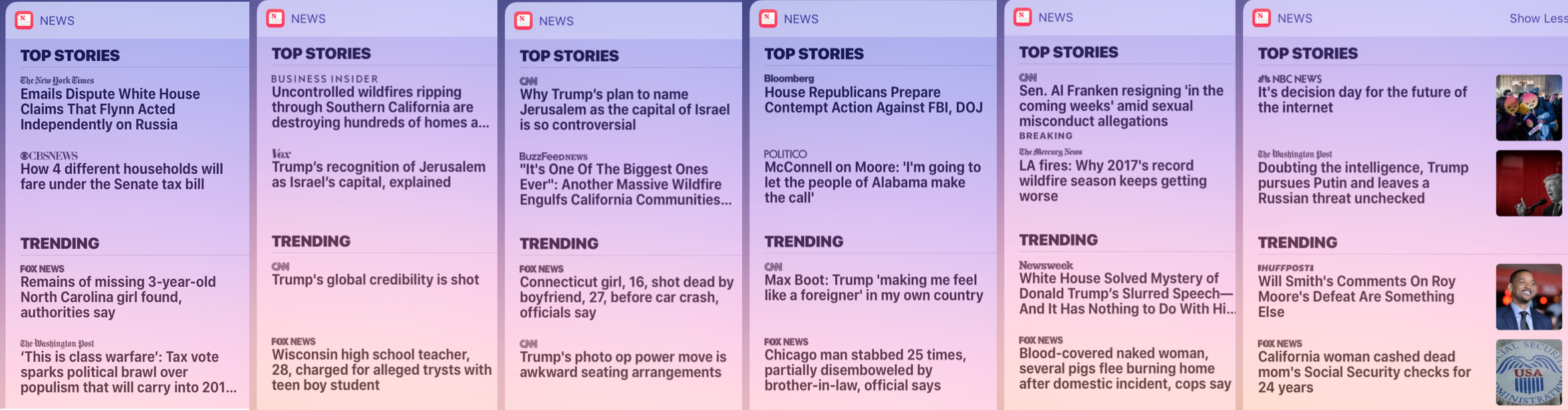

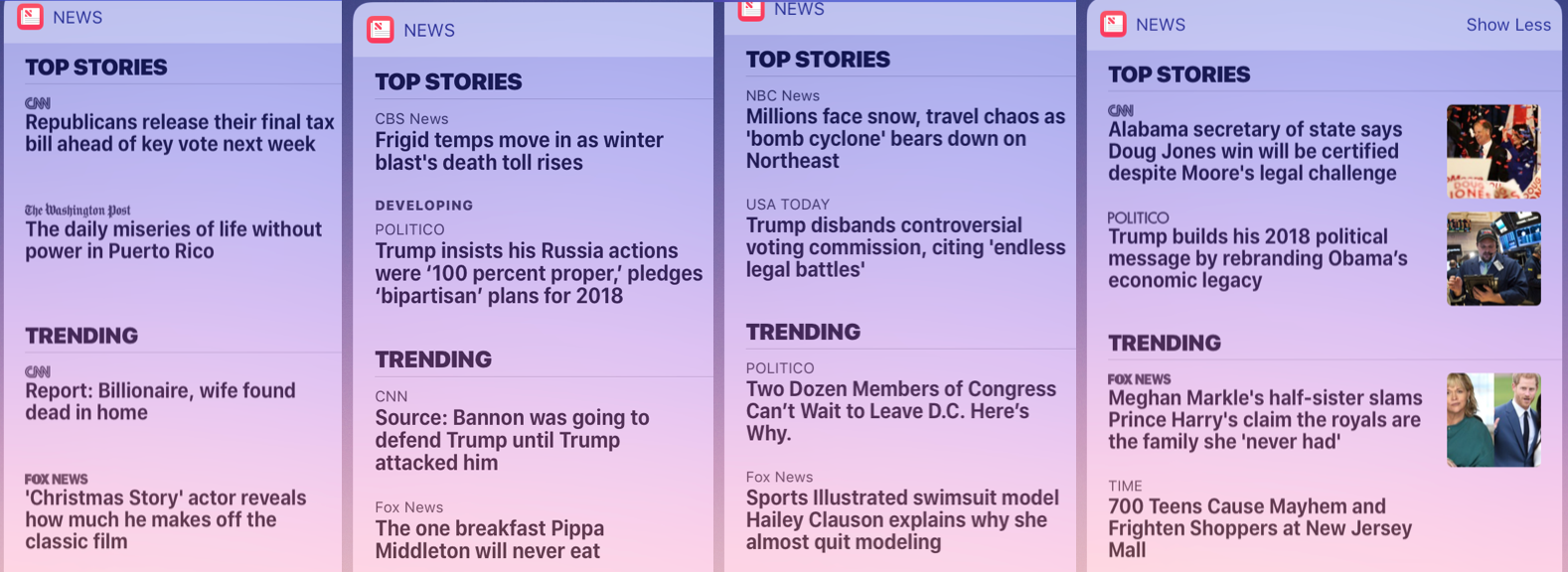

A really powerful sociological image popped up in my Twitter feed that makes the point beautifully. We actually did find some common ground this week through a trend that united the country across red states and blue states:

It is tempting to focus on protests as a story about conflict alone, and conflict certainly is there. But it is also important to realize that this week’s protests represent a historic level of social consensus. The science of cooperation and social movements reminds us that getting collective action started is hard. And yet, across the country, we see people not only stepping up, but self-organizing groups to handle everything from communication to community safety and cleanup. In this way, the protests also represent a remarkable amount of agreement that the current state of policing in this country is simply neither just nor tenable.

I was struck by this image because I don’t think nationwide protests are the kind of thing people have in mind when they call for everyone to come together, but right now protesting itself seems like one of the most unifying trends we’ve got. That’s the funny thing about social cohesion and cultural consensus. It is very easy to call for setting aside our differences and working together when you assume everyone will be rallying around your particular way of life. But social cohesion is a group process, one that emerges out of many different interactions, and so none of us ever have that much control over when and where it actually happens.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, on Twitter, or on BlueSky.