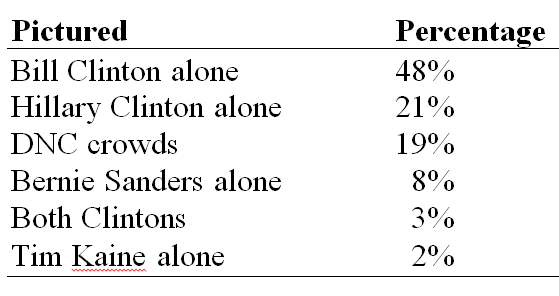

On Tuesday the first female presidential candidate was officially nominated by a major party. Newspaper headlines across the country referenced the historic event with headlines like “Historic First!” and “Clinton Makes History!” but a surprising number featured photographs of Bill instead of Hillary Clinton. I coded the pictures of each of the 266 newspapers that ran the story on the front page on July 27th (cataloged at Newseum). Here’s the breakdown:

On Tuesday the first female presidential candidate was officially nominated by a major party. Newspaper headlines across the country referenced the historic event with headlines like “Historic First!” and “Clinton Makes History!” but a surprising number featured photographs of Bill instead of Hillary Clinton. I coded the pictures of each of the 266 newspapers that ran the story on the front page on July 27th (cataloged at Newseum). Here’s the breakdown:

Somehow more than three-quarters of newspapers used photos of someone other than the nominee. Nearly the same number of newspapers showed pictures of the crowd at the DNC as the number that showed Hillary Clinton. A non-trivial number of newspapers only showed pictures of Senator Bernie Sanders and a few featured pictures of Vice Presidential Nominee Tim Kaine.

So, why? Why did nearly half of the U.S. newspaper front pages Wednesday morning show only pictures of Bill Clinton?

Let’s consider some explanations.

(1) Journalistic norms. Journalism is governed by a set of norms. One requires that any photo that illustrates an event should be taken from the event itself. Some have suggested that since Hillary Clinton wasn’t physically in attendance at the convention Tuesday evening, reporters couldn’t use a photograph of her. That fact that 21% of newspapers did use an image of Hillary Clinton, though, suggests that this can’t fully explain the numbers. Of the 55 images of Hillary Clinton, 21 used photographs of her video appearance at the convention; the rest used file photos. She may not have physically been there, but front pages like that of The Boston Globe and Newsday (below) show that journalistic norms can’t explain her overwhelming absence.

(2) Hostile sexism. Sexism that’s hostile is aggressively and proactively anti-woman. Is it possible that some journalists are so uncomfortable with or opposed to a female presidential nominee that they just couldn’t stomach putting Hillary Clinton’s face on the front page? Maybe. There might be a few overtly sexist journalists who just refused to put Hillary on the cover, but that probably doesn’t explain such a high percentage of newspapers with no picture of the nominee.

(2) Hostile sexism. Sexism that’s hostile is aggressively and proactively anti-woman. Is it possible that some journalists are so uncomfortable with or opposed to a female presidential nominee that they just couldn’t stomach putting Hillary Clinton’s face on the front page? Maybe. There might be a few overtly sexist journalists who just refused to put Hillary on the cover, but that probably doesn’t explain such a high percentage of newspapers with no picture of the nominee.

(3) Supportive sexism. Perhaps journalists (unconsciously) felt that an important thing about her nomination was that she was endorsed by men. Political authority – the authority to speak in the public about political issues — is a masculine authority usually held by men. As a male politician and former president, Bill Clinton’s image lends authority to Hillary Clinton’s historic nomination. His words about her (his “nod”) have weight, giving legitimacy to her candidacy for an office that has always been held by a man. Headlines read “He’s With Her!” and another said “Bill makes his case!” She earned “Bills praise” and got a “boost.” Maybe some journalists intuited that that was the real story.

(4) Bill Clinton’s own gender barrier. Former President Bill Clinton also gave a historic speech Tuesday evening as the first male spouse of the first female presidential candidate. As Rebecca Traister wrote for New York Magazine, “for the first time, the spouse wasn’t a wife. It was a husband, who was … [performing] submission.” Perhaps men’s gender bending is more inherently interesting since masculinity is more limiting for men than femininity is for women. Or maybe this is a more subtle form of sexism: finding things men do inherently more interesting just because men are doing them.

(5) A (gendered) failure of imagination. Maybe Bill Clinton appeared on so many covers because there was no one in the newsroom to notice that putting him on the front page was weird. Or no one with the authority and gall to speak up and say, “Uh, shouldn’t we use a picture of Hillary instead of Bill?” This may reflect the gender gap in journalism. Three out of five print journalists are male. It’s probably even more skewed at the top. With so many male journalists working on front pages across the country, it is plausible that they just didn’t think about gender or those that did were afraid to speak up.

All these explanations together, and likely ones I haven’t thought of, help explain why Hillary Clinton’s face was so absent from the story about her historic moment. The consequences are significant. Politics is still largely a man’s world, and conceptualized in terms of masculinity. U.S. politicians are overwhelmingly male. Only 6 state governors are female, and only 19.3% of U.S. representative seats are filled by women. Only 20 women serve in the U.S. senate. Showing images of a male politician, Bill Clinton, when a female politician has earned an historic victory, only continues this gendered order of politics.

Wendy M. Christensen is a professor of sociology at William Paterson University. Her research interests center on gender, the media, political mobilization, and the U.S. Armed Forces. You can follow her on twitter at @wendyphd.