You may be familiar with the fact that the coca in Coca-Cola was originally cocaine. But did you know that the reason we infused such a beverage with the drug in the first place was because of prohibition? Cocaine cola replaced cocaine wine. In fact, when it was debuted in 1886, it was described as “Coca-Cola: The Temperance Drink.”

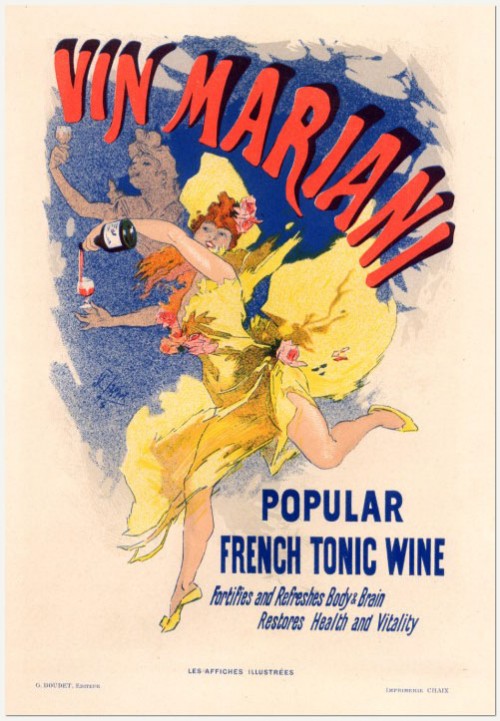

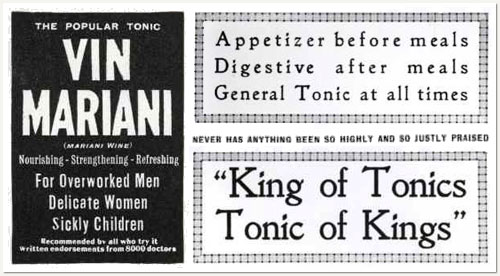

The first mass marketed cocaine product was Vin Mariani, a cocaine-infused Bordeaux introduced in the 1860s. Legal and requiring no prescription, it was believed to “restore health and vitality” and I’m sure it felt like it did. Wikipedia reports that it included 7.2 mg of cocaine per ounce; comparatively, a line snorted is about 25 mg.

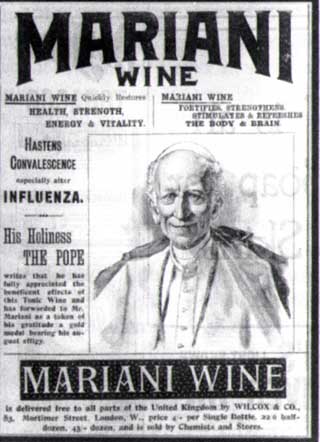

Yes, Vin Mariani was good for men, women, and children. The “tonic of kings!” Even the Pope! He loved it so much he called it a “benefactor of humanity” and gave it a Vatican Gold Medal:

But he was just the most eminent of its fans. Mariani’s media blitz included endorsements from Sarah Bernhardt, H.G. Wells, Ulysses S. Grant, Queen Victoria, the Empress of Russia, Thomas Edison, and the then-President of the United States, William McKinley. Jules Verne reportedly joked: “Since a single bottle of Mariani’s extraordinary coca wine guarantees a lifetime of 100 years, I shall be obliged to live until the year 2700!”

Vin Mariani dominated the market, but there was an American chemist, John Smith Pemberton, who made a competing product: Pemberton’s French Wine Coca. He described it as an “intellectual beverage.” Pemberton was located in — you guessed it, Atlanta — and the state enacted temperance legislation in 1885. Hence, Coca-Cola was born.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.