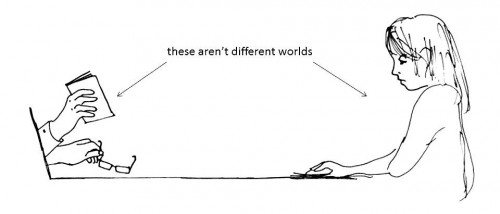

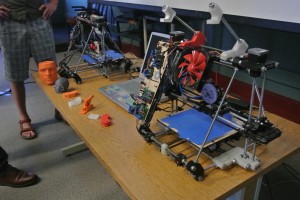

The price of 3D printers is plummeting. Like all complicated pieces of technology it is quickly moving from large, confusing, and expensive to small, simple and cheap. This year has been full of consumer-level 3D printers that are cheaper than some professional grade photo printers. Right now, these little things are capable of making plastic do-dads that are, admittedly, of lesser quality than some dollar store toys. But just like a magic trick, you’re not paying for the physical thing, you’re paying for the ability to do the trick. Design an object in a modeling software suite like SketchUp, convert it into some kind of printer-friendly format, and -so long as it is smaller than a bread box and made out of plastic- you can build whatever you want. 3D printers give an individual the ability to transform bits into atoms. In some ways it is a radical democratization of the means of production. For a fraction of the price of a car, someone can gain the ability to fabricate a relatively wide range of material objects. What are the implications for this new ability? What does it say about the relationship of atoms and bits? more...