The National Weather Service estimates that Hurricane Florence dropped over 8 trillion gallons of rain across North Carolina, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has just started evaluating how much damage was done. While Hurricane Florence and other natural disasters impact thousands of lives every year, not all groups recover equally. Recent research reported by Mic reveals that non-white households tend to lose wealth after a natural disaster, while white households often profit.

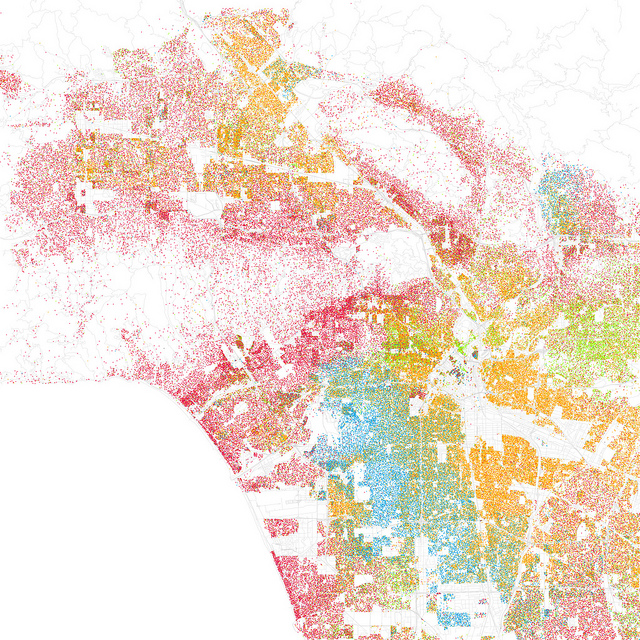

Tracking families from 1999 to 2013, sociologists Junia Howell and Jim Elliot found that white families in the most disaster-hit counties gained $126,000 in wealth on average over the 14 years of the study. By contrast, Back, Latinx, and Asian families in the same counties lost $27,000, $29,000 and $10,000 respectively. “Put another way, whites accumulate more wealth after natural disasters while residents of color accumulate less,” Elliot explained.

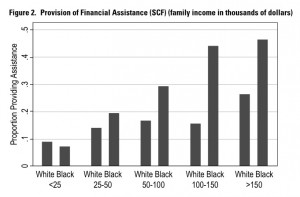

After a natural disaster, FEMA provides grants and low-interest loans to offset the cost of property damage. While it would make sense that federal disaster relief would mitigate racial disparity, Howell and Elliot’s research shows that it actually makes it worse. Counties receiving the most FEMA aid experienced the starkest widening of the racial wealth gap. Black families in counties that received the least FEMA aid accumulated $82,000 more wealth on average than Black families in counties that received the most aid. The researchers tried to explain this puzzling finding:

“Based on previous work on disasters such as hurricanes Katrina and Harvey, we know FEMA aid is not equitably distributed across communities … When certain areas receive more redevelopment aid and those neighborhoods also are primarily white, racial inequality is going to be amplified.”

In other words, one potential explanation for this trend is that white communities within counties receiving federal aid tend to receive more investment for rebuilding after a disaster than non-white communities in the same county. And with climate change increasing the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, this discovery implies worsening racial wealth gaps in the future. However, Howell and Elliot see reason to be hopeful,

“The good news is that if we develop more equitable approaches to disaster recover, we can not only better tackle that problem but also help build a more just and resilient society.”