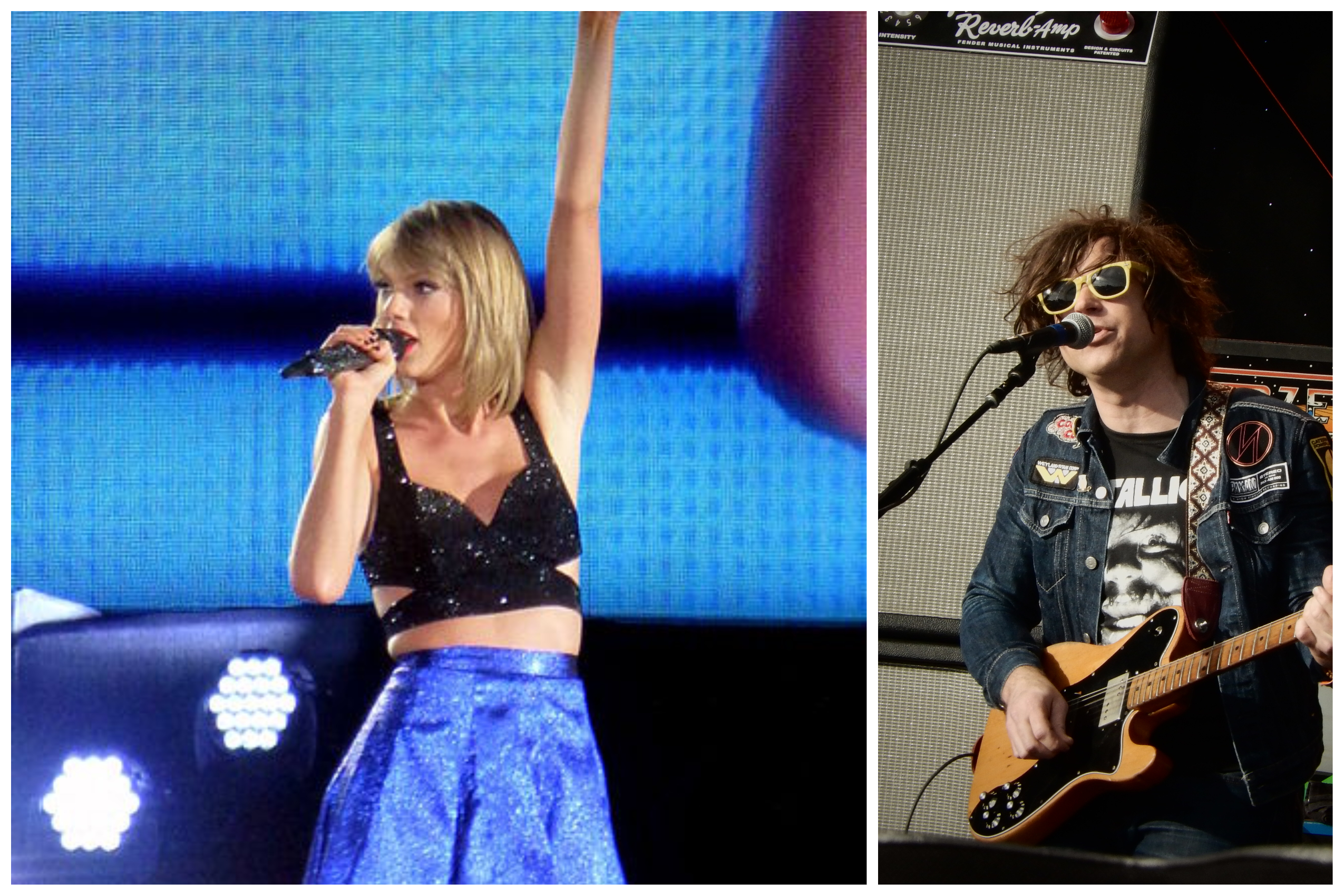

In 2019, after this post was published, Ryan Adams was accused of engaging in a pattern of manipulative behavior including verbal, emotional, and sexual harassment. You can read more of this coverage here. (Updated, October 26, 2022)

The release of Ryan Adams’ cover of Taylor Swift’s 1989 resulted in a media frenzy about which album is “better” and who deserves credit for the “depth and complexity” that many say Adams brought to Swift’s poppier original. Some reviews argue Adams “vindicated” Taylor Swift as an artist; others argue that emotional depth was already present in Swift’s songwriting and reviews of Adams’ cover operate under gendered understandings of emotions and legitimacy in pop music. Many publications that reviewed Adams’ version did not review Swift’s original. Ironically, the albums will be competing for a Grammy this year, and many think Adams will take it over Swift. Sociological studies of popular music show how gender affects who gets credit for creativity in the industry.

Research finds that male musicians, regardless of genre, are more likely to receive critical recognition and be “consecrated” into the popular music canon. Women are less likely to be seen as “legitimate” artists and are more often judged on their emotional authenticity and connections with “more” legitimate, male artists. Further, newspapers and music critics are more likely to cover music written and produced by male artists.

- Vaughn Schmutz and Alison Faupel. 2010. “Gender and Cultural Consecration in Popular Music.” Social Forces 89(2): 685-707

- Vaughn Schmutz. 2009. “Social and Symbolic Boundaries in Newspaper Coverage of Music, 1955–2005: Gender and Genre in the US, France, Germany, and the Netherlands.” Poetics 37(4): 298-314

Style doesn’t stem from the artist’s creative mind alone. Musical genres are gendered, as well as raced and classed. Industry norms require women and men to adopt different styles depending on the music genre in which they work. For example, women are more often expected to be sexual and/or emotional in their presentation of self and their music.

- Patti Lynne Donze. 2011. “Popular Music, Identity, and Sexualization: A Latent Class Analysis of Artist Types.” Poetics 39: 44-63.

- Diana Miller. 2014. “Symbolic Capital and Gender: Evidence from Two Cultural Fields.” Cultural Sociology 8(4): 462–482.

For more on gender in culture industries, check out this Discovery on fashion design.