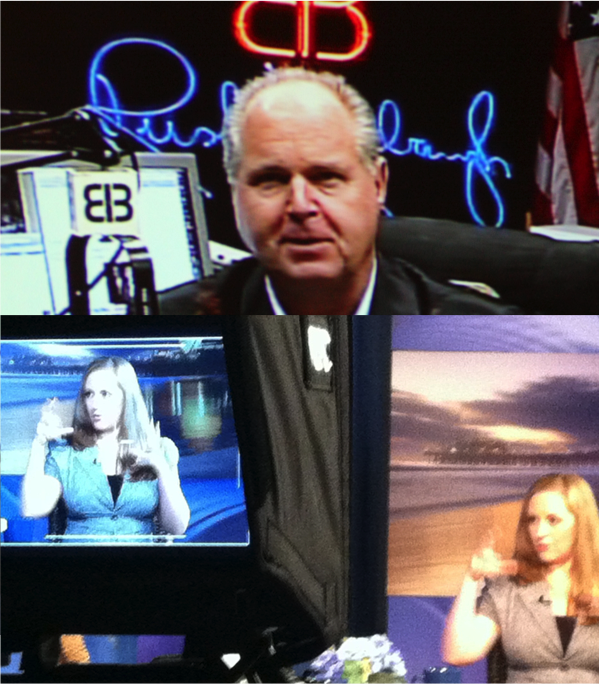

During his April 1 on-air radio show, Rush Limbaugh cited a recent SocImages post titled, “Are Economics Majors Anti-Social?” In debating the content of the post, Limbaugh frequently referred to author and editor Lisa Wade as “professorette.” In making up this word, he intentionally gendered the gender-neutral title “professor.” Given the cultural devaluation of femininity, the unnecessary gendering of Wade’s profession signals a discounting of her position and expertise. While Wade is, notably, the author (with Myra Marx-Ferree) of the new book, Gender, women of all professions face challenges to their legitimacy.

During his April 1 on-air radio show, Rush Limbaugh cited a recent SocImages post titled, “Are Economics Majors Anti-Social?” In debating the content of the post, Limbaugh frequently referred to author and editor Lisa Wade as “professorette.” In making up this word, he intentionally gendered the gender-neutral title “professor.” Given the cultural devaluation of femininity, the unnecessary gendering of Wade’s profession signals a discounting of her position and expertise. While Wade is, notably, the author (with Myra Marx-Ferree) of the new book, Gender, women of all professions face challenges to their legitimacy.

Education, prestige, and capital do not exempt women from sexist stereotypes about incompetency. Female researchers and professors are often viewed as less competent than their male colleagues, and male-dominated academic disciplines are perceived to draw more innately brilliant and talented practitioners than female-dominated disciplines.

- Rhea E. Steinpreis, Katie A. Anders, Dawn Ritzke. 1999. “The Impact of Gender on the Review of the Curricula Vitae of Job Applicants and Tenure Candidates: A National Empirical Study.” Sex Roles 41(7-8): 509-528.

- Lillian MacNell, Adam Driscoll, and Andrea N. Hunt. 2014. “What’s in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching.” Innovative Higher Education 1–13.

- Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham, and Jo Handelsman. 2012. “Science Faculty’s Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(41):16474–79.

- Sarah-Jane Leslie, Andrei Cimpian, Meredith Meyer, and Edward Freeland. 2015. “Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines.” Science 347: 262-265.

Even when women occupy high status positions of expertise they are more likely to be interrupted than men. Furthermore, men are more likely to interrupt women even when women occupy a higher professional prestige, suggesting that the gender hierarchy can be more influential to power dynamics than professional status.

- Adrienne B. Hancock and Benjamin A. Rubin. 2015. “Influence of Communication Partner’s Gender on Language.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 34(1):46–64.

- Candace West. 1984. “When the Doctor is a ‘Lady’: Power, Status, and Gender in Physician-Patient Encounters.” Symbolic Interaction 7(1): 87-106.

Women are also limited in the range of emotions and behaviors they can exhibit in the workplace without being judged negatively. Emotional displays of anger, for example, are interpreted differently if exhibited by men or women, to the likely disadvantage of women. Additionally, displays of dominance by agentic (that is, self-organizing and proactive) female leaders are subject to dominance penalties, backlash, and prejudice.

- Victoria L. Brescoll and Eric Luis Uhlmann. 2008. “Can an Angry Woman Get Ahead? Status Conferral, Gender, and Expression of Emotion in the Workplace.” Psychological Science 19(3):268–75.

- Laurie Rudman, Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, Julie E. Phelan, and Sanne Nauts. 2012. “Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 165-179.

Curious what our friends in sociolinguistics have to say about gendered titles? Consider listening to Lexicon Valley’s exploration of feminine word endings here.