As Black History month draws to a close, it’s important to celebrate the work of Black scholars that contributed to social science research. Although the discipline has begun to recognize the foundational work of scholars like W.E.B. DuBois, academia largely excluded Black women from public intellectual space until the mid-20th century. Yet, as Patricia Hill Collins reminds us, they leave contemporary sociologists with a a long and rich intellectual legacy. This week we celebrate the (often forgotten) Black women who continue to inspire sociological studies regarding Black feminist thought, critical race theory, and methodology.

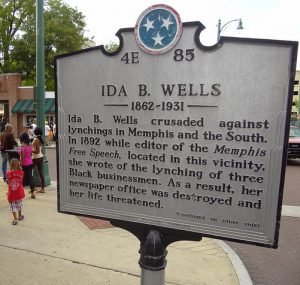

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was a pioneering social analyst and activist who wrote and protested against many forms of racism and sexism during the late 19th and early 20th century. She protested Jim Crow segregation laws, founded a Black women’s suffrage movement, and became one of the founding members of the NAACP. But Wells is best-known for her work on lynchings and her international anti-lynching campaign. While Wells is most commonly envisioned as a journalist by trade, much of her work has inspired sociological research. This is especially true for her most famous works on lynchings, Southern Horrors (1892) and The Red Record (1895).

In Southern Horrors (1892), Wells challenged the common justification for lynchings of Black men for rape and other crimes involving white women. She adamantly criticized white newspaper coverage of lynchings that induced fear-mongering around interracial sex and framed Black men as criminals deserving of this form of mob violence. Using reports and media coverage of lynchings – including a lynching of three of her close friends – she demonstrated that lynchings were not responses to crime, but rather tools of political and economic control by white elites to maintain their dominance. In The Red Record (1895), she used lynching statistics from the Chicago Tribune to debunk rape myths, and demonstrated how the pillars of democratic society, such as right to a fair trial and equality before the law, did not extend to African American men and women.

- Paula Giddings. 2008. Ida: A Sword among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching. Amistad.

- Patricia Madoo Lengermann and Gillian Niebrugge. 2006. The Women Founders: Sociology and Social Theory 1830–1930, A Text/Reader. Waveland Press.

Anna Julia Cooper (1858-1964) was an avid educator and public speaker. In 1982, her first book was published, A Voice from the South: By A Black Woman of the South. It was one of the first texts to highlight the race- and gender-specific conditions Black women encountered in the aftermath of Reconstruction. Cooper argued that Black women’s and girls’ educational attainment was vital for the overall progress of Black Americans. In doing so, she challenged notions that Black Americans’ plight was synonymous with Black men’s struggle. While Cooper’s work has been criticized for its emphasis on racial uplift and respectability politics, several Black feminists credit her work as crucial for understanding intersectionality, a fundamentally important idea in sociological scholarship today.

- Vivian M. May. 2012. Anna Julia Cooper, Visionary Black Feminist. Routledge.

As one of the first Black editors for an American Sociological Association journal, Jacquelyn Mary Johnson Jackson (1932-2004) made significant advances in medical sociology. Her work focused on the process of aging in Black communities. Jackson dismantled assumptions that aging occurs in a vacuum. Instead, her scholarship linked Black aging to broader social conditions of inequality such as housing and transportation. But beyond scholarly research, Jackson sought to develop socially relevant research that could reach the populations of interest. As such, she identified as both a scholar and activist and sought to use her work as a tool for liberation.

- Delores P. Aldridge. 2008. Imagine a World: Pioneering Black Women Sociologists. University Press of America.

Together, these Black women scholars challenged leading assumptions regarding biological and cultural inferiority, Black criminality, and patriarchy from both white and Black men. Their work and commitment to scholarship demonstrates how sociology may be used as a tool for social justice. Recent developments such as the #CiteBlackWomen campaign draw long-overdue attention to their work, encouraging the scholarly community to cite Wells, Cooper, Jackson, and other Black women scholars in our research and syllabi.