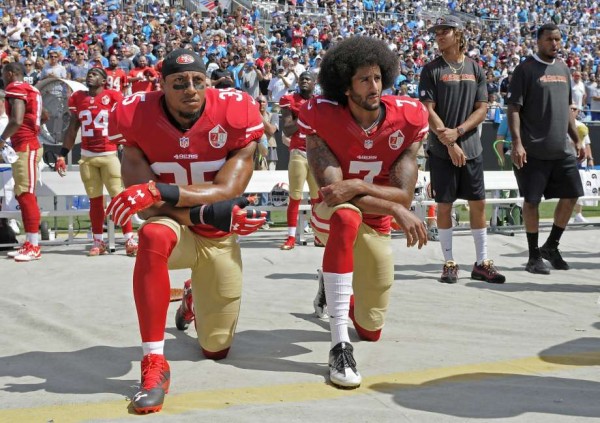

More and more athletes are joining the San Francisco 49ers’ Colin Kaepernick in kneeling during the “Star Spangled Banner” at the beginning of sporting events. Though this phenomenon has spurred controversy and heated exchanges, sports stars using their celebrity for civic action is not entirely new. After the police shootings of Eric Gardner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and other unarmed black people, numerous members of the NBA and NFL wore hoodies that read “I Can’t Breathe,” (Eric Gardner’s last words); others entered the game while making the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” gesture championed by #BlackLivesMatter. Indeed, today we are witnessing a resurgence of athlete advocacy.

A common criticism of these athletes is that “they should just stick to sports!” or that “they aren’t supposed to talk about politics!” In reality, however, athletes have been at the forefront of protests and civic action for some time now, particularly in the 1960s. TSP Editor Doug Hartmann’s popular book describes how the Civil Rights Movement provided the context for athletes to begin using their celebrity for greater causes. Similarly, Ben Carrington describes how racism has shaped the international black-athlete-experience. Colonialism and contemporary globalization have made sports a site where racism is enacted and solidified, meaning athletes have had to think about these concepts–and fight against them–for a long time.

- Douglas Hartmann. 2003. Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and their Aftermath. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Ben Carrington. 2010. Race, Sport and Politics: The Sporting Black Diaspora. Sage Publications.

After the Civil Rights movement, athlete protests became less common, especially as athletes expanded into areas like merchandising and marketing, which meant that they were more likely to avoid “rocking the boat” and jeopardizing their business. But because of #BlackLivesMatter and a greater national focus on police killings of unarmed black people, athletes are once again getting into the fray. As Herbert Ruffin describes, politicizing college sports has led student athletes to protest for their own rights and demands — remember the events at Ole Miss last year? Similarly, Emmett Gill describes actions (and reactions) surrounding the “Ferguson Five” — the St. Louis Rams football players who showed solidarity with protesters in Ferguson, Missouri.

- Herbert G. Ruffin II. 2014. “Doing the Right Thing for the Sake of Doing the Right Thing”: The Revolt of the Black Athlete and the Modern Student-Athletic Movement, 1956-2014. Western Journal of Black Studies, 38(4).

- Emmett E Gill Jr. 2016. “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” or Shut Up and Play Ball? Fan-generated Media Views of the Ferguson Five. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 26(3-4): 400-412.

This research shows that while athlete activism is often met with criticism, it does not mean that their tactics will prove unsuccessful. If history or recent events have shown us anything, the opposite may be truer. One thing is for sure — athlete protest in the contemporary era is just warming up.

For even more readings on race, sports, and athlete activism, check out the #ColinKaepernickSyllabus created by NewBlackMan (in Exile).