An understanding of the sociological imagination can be difficult in our very individually focused society. As a topic, the sociological imagination is usually the first or second class of every introduction to sociology course. Teaching topics by relating them to students’ immediate context (especially early in the semester) is one way to help them see how the sociological imagination works.

An understanding of the sociological imagination can be difficult in our very individually focused society. As a topic, the sociological imagination is usually the first or second class of every introduction to sociology course. Teaching topics by relating them to students’ immediate context (especially early in the semester) is one way to help them see how the sociological imagination works.

So…how can we use the sociological imagination to help students understand why they are sitting there in the classroom? Especially for first year students, the seemingly very individual process of deciding if and where to go to college is fresh in their minds.

C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) presents the sociological imagination as the ability to see the relationship between one’s individual life and the effects of larger social forces. One way to help students see all the external forces that have influenced their arrival in your classroom is to push them to answer the question: “Why did you enroll in college?”

“To learn.” Can’t you learn on your own? Studying what you want, when you want at a much lower cost?

“Okay, so to earn a degree.” This is a great place to talk about how our society is increasingly credentialed. The college, accrediting organizations, deans, professional associations all define what it takes to be awarded a degree, a certificate that serves as a cultural symbol of legitimation and distinction, helping to sort people into categories. You see these hung on walls in offices to signal expertise to others. As an individual, you make choices, but those choices are influenced by a modern social context that makes the consequences of those choices very real.

“If I don’t have a degree, I won’t get a good job.” After WWII, the options for those with a high school diploma to earn a middle class living in the US were far greater than they are now. The largely successful effort of companies to break unions have greatly decreased the number of employees that can collectively bargain with management. Additionally, neoliberal globalization of the economy has contributed to deindustrialization – many manufacturing jobs have moved to less developed countries with lower wages. The context with which individuals make decisions changed, the social context changed.

“If I don’t get a good job I will struggle to afford housing, health care, and a college education for any children I have.” Additionally, we live in an economic market that requires people to earn wages, mostly by selling their labor (hello Marx). Few if any of your students will work for themselves, own a business, or avoid wage labor. Their “choice” to pursue a college degree was hardly a choice. This can be seen by exploring the alternative…what would they be doing if they were not in college? Compared to many other advanced industrialized nations, the US has a weak social safety net that leaves individuals vulnerable to market forces.

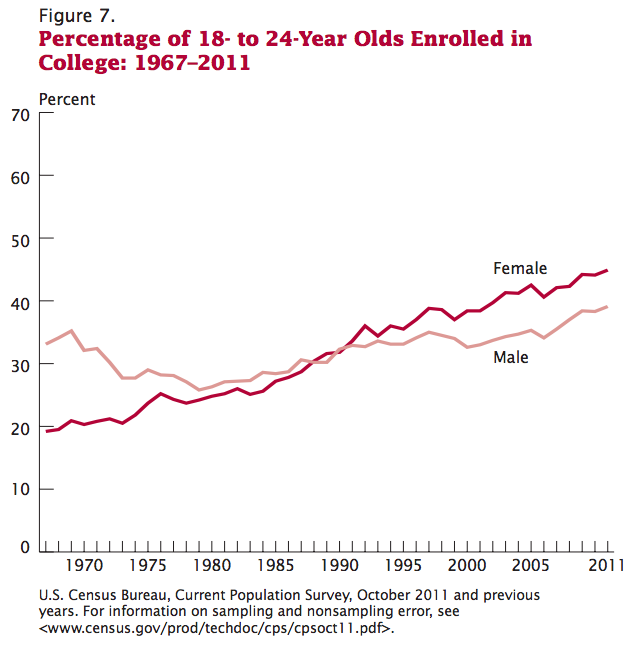

While embedded in the time, place, and structure of our own society, it may be difficult to see the social forces that Mills encouraged us to see in order to more fully understand our world. By looking at college enrollment rates over time, students can see that the historical moment, the society, that they occupy now is very different compared to 50 years ago. Mills speaks of the intersection between history and biography. Looking at a different point in time shows us how our biography may have been different. Especially for women, the likelihood that they would have been enrolled in college if they were transported back to 1967, a different social context, is much smaller. More than double the rate of women are now enrolled.

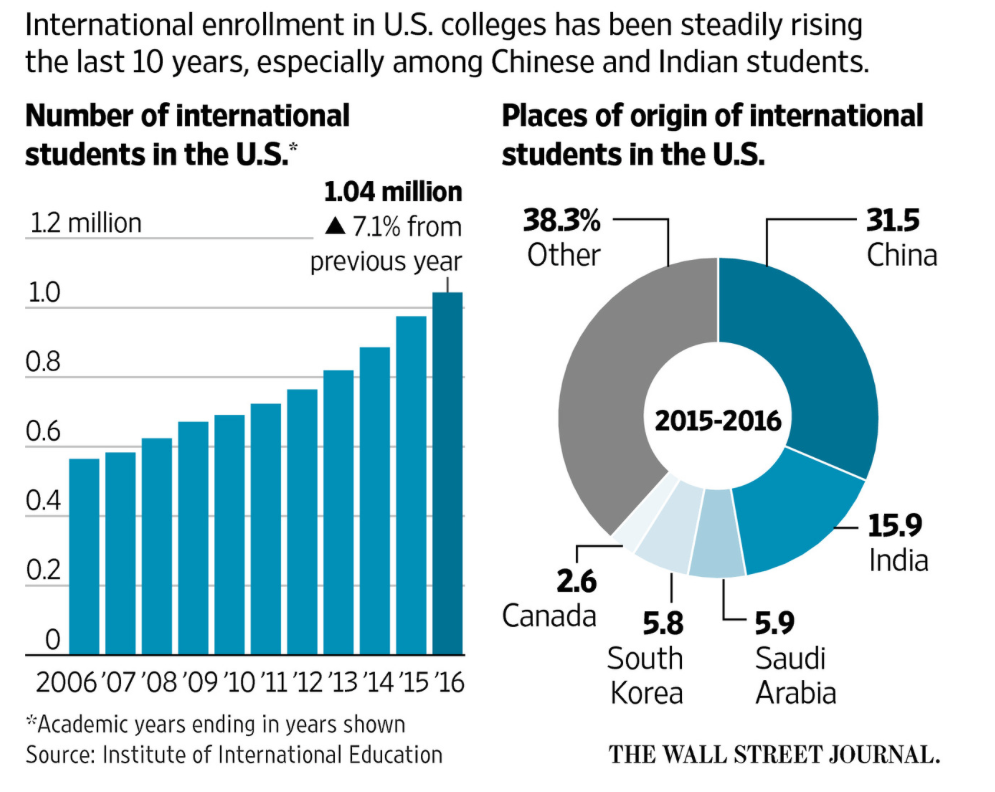

Increasingly, international students make up larger portion of the student body at colleges and universities in the US. This is a dramatic change from your parents experiences in higher education and has been largely facilitated by changes in our social context: increasing globalization, financial stress of colleges and universities, changing demographic distributions in the US that will decrease the overall number 18 year olds applying to college.

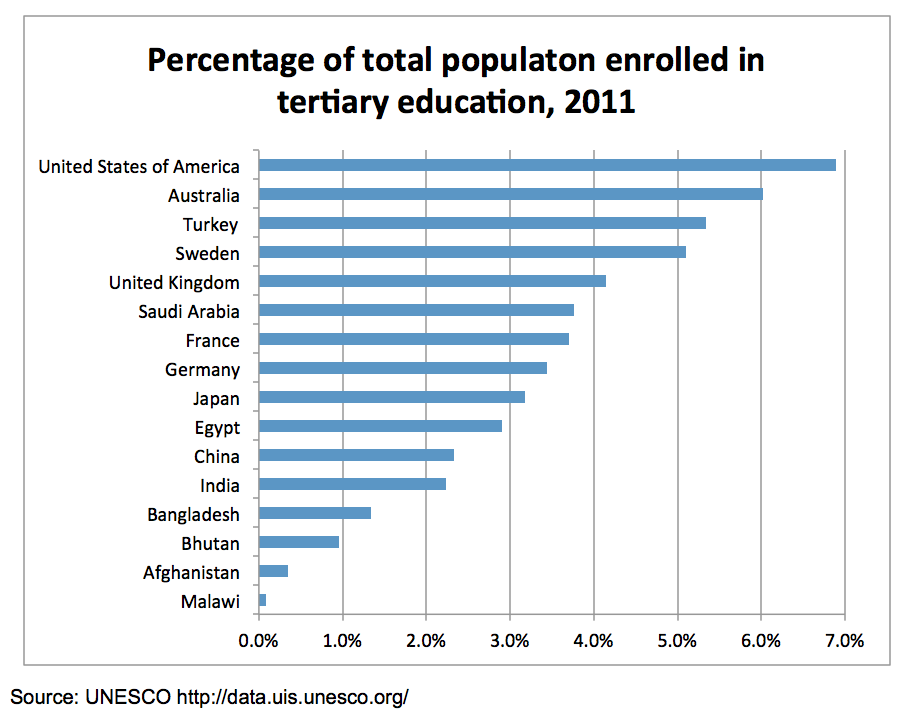

Enrollment levels in other nations today also help us use our sociological imagination and to see that society has an influence on our individual decisions. The figure below shows UNESCO data for 2011 enrollment in tertiary education (post-secondary of any type, including college) across select nations.

Living in a different society, with different resources, economy, culture, and institutions would dramatically alter your “individual” decision to enroll in college. To understand this is to use the sociological imagination.

Society not only influence how many people go to college, but a college education influences society in many ways as well.

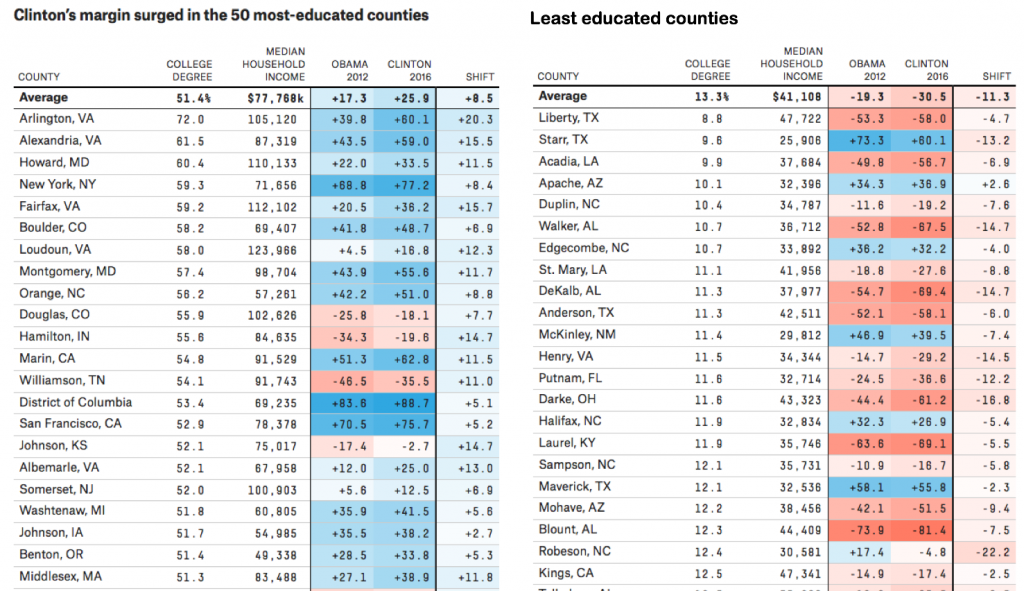

In the most recent presidential election, the counties with the highest rate of college educated citizens overwhelmingly voted for Hillary Clinton. While the counties with the lowest rates of college educated population voted for Trump.

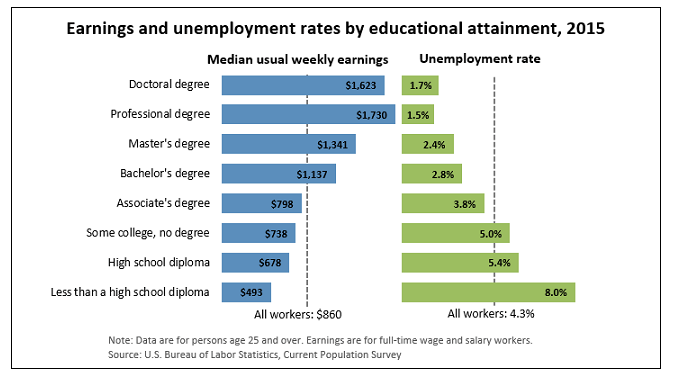

Not surprisingly, people with higher levels of education in today’s society earn more money and have lower rates of unemployment on average.

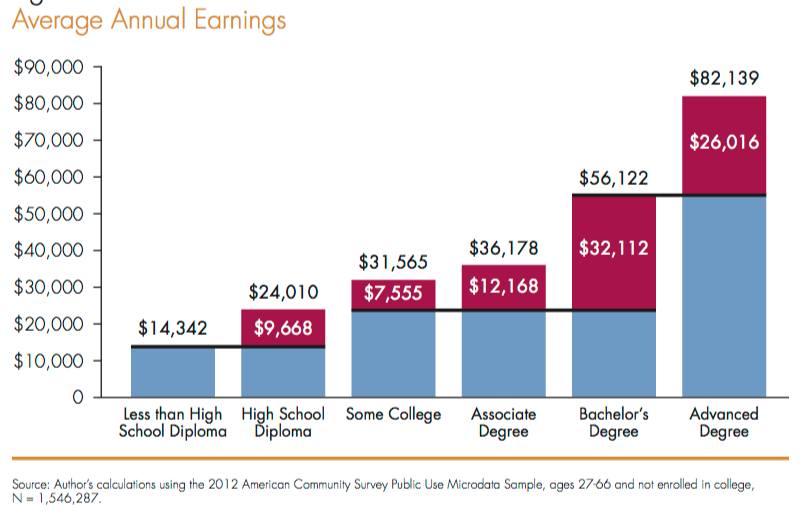

Here is another way of looking at that shows, on average, how much more people earn per advancement in education.

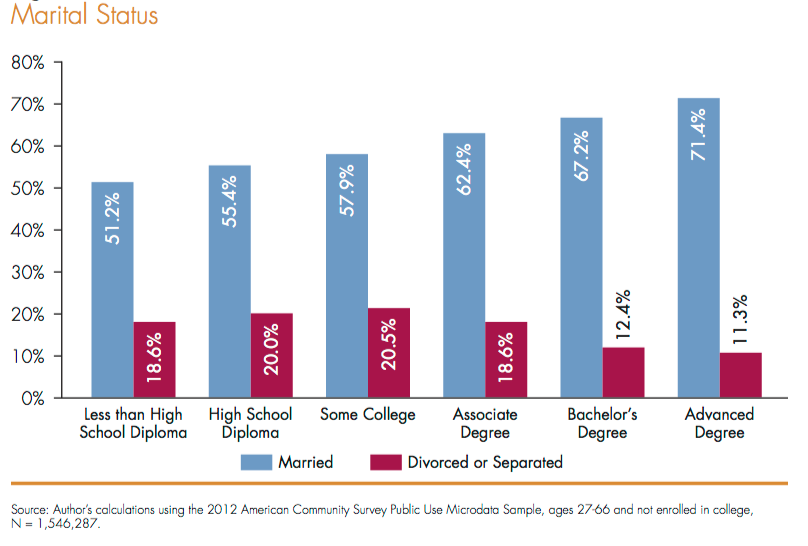

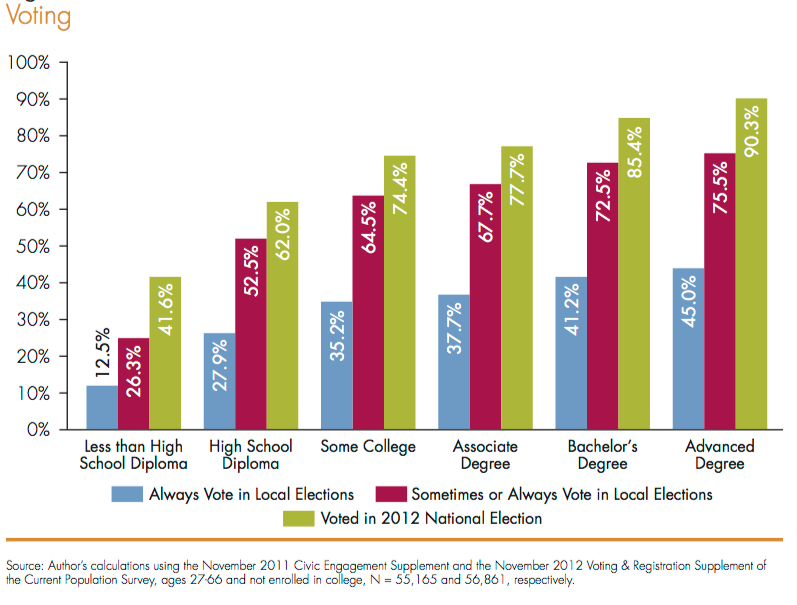

Also, the greater the education level, the more likely to be married and he more likely to vote.

Teach well, it matters.

Additional resources:

See my previous post on illuminating the sociological imagination by looking at marriage across time and other cultures.

Massengill, Rebekah Peeples. 2011. “Sociological Writing as Higher-level Thinking: Assignments that Cultivate the Sociological Imagination.” Teaching Sociology 39(4): 371-381.

Nell Trautner, Mary; Borland, Elizabeth. 2013. “Using the Sociological Imagination to Teach about Academic Integrity.” Teaching Sociology 41(4): 377-388.

Noy, Shiri. 2014. “Secrets and the Sociological imagination: Using PostSecret.com to Illustrate Sociological Concepts.” Teaching Sociology 42(3): 187-19

Packard, Josh. 2013. “The Impact of Racial Diversity in the Classroom: Activating the Sociological Imagination.” Teaching Sociology 41(2): 144-158.

Unnithan, N. Prabha. 1994. “Using Students’ Familiarity and Knowledge to Enliven Large Sociology Classes.” Teaching Sociology 22(4): 333-336.

Comments 5

Shawndra Barnes — August 23, 2016

This was a very interesting perspective. I guess I never really thought of it this way, but it is very true. I am a non traditional student and I know first hand that it is a struggle trying to survive without a degree. I went so long trying to make ends meet that I finally realized if I want to be successful and financially less stressed, I had to go back to school. Though it was a choice I made it was also the only financial improvement choice that was available and also legal. Therefore it did not quite feel like a choice as much as a necessity in today's society.

TEACHING SOCIOLOGY: Tools to start a new semester - Sociology Toolbox — January 10, 2018

[…] second one examines higher education and the act of deciding to come to college through a sociological lens. […]

Tristan — July 5, 2018

I did not know that

Tristan Hicks — July 8, 2018

Cool

John — June 23, 2019

Not a huge surprise about the female to male discrepancy in higher education. When the faculty is made up of over 75 percent female, the instrcutors bias , and sexual preference goes up.