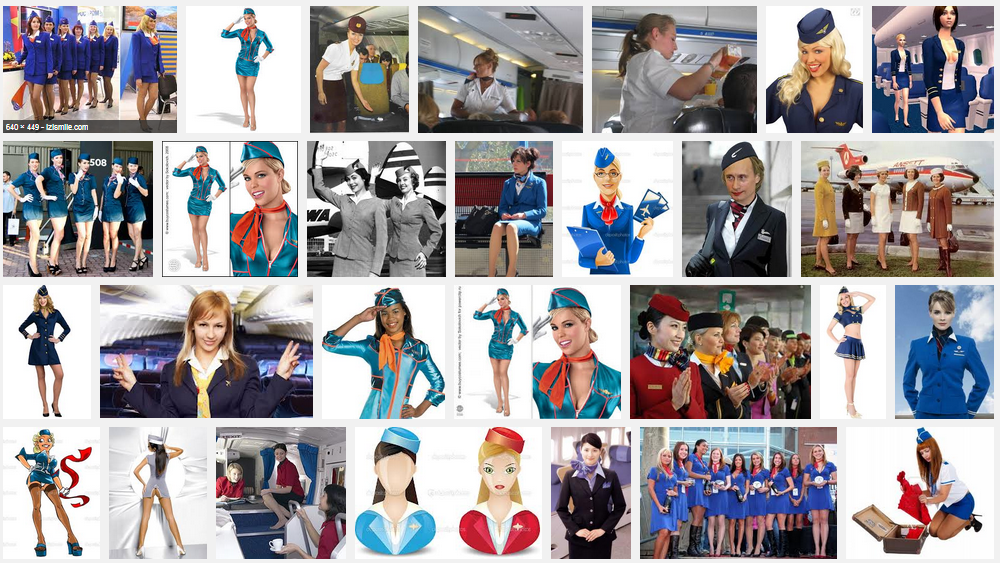

We have an ever-growing collection of ways in which men are frequently positioned as people and women as women. We’re always on the lookout for new examples and sociologist Nathan Palmer recently highlighted a nice observation about how this happens in language.

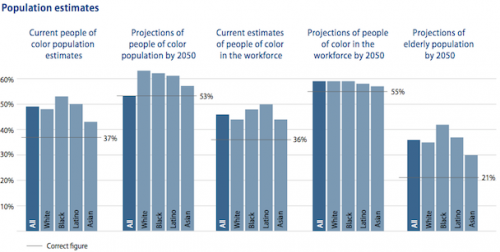

He asked readers to consider a quote from a textbook (not to single Conley out, he’s using standard language and I use it as well in my own textbook). Here’s the quote with the relevant part in bright white:

Applying an insight by sociologist Michael Kimmel, Palmer then updated the slide with slightly different language:

If a dollar is the amount by which all other wages should be compared, then the first sentence centers men’s experiences and positions women as a deviation from that. The second sentence switches that around.

By switching the referent, this change in language shifts the center of the discussion from women’s disadvantage to men’s advantage. Of course, there is both unfair disadvantage and advantage in this story, and we need to make both visible, but always talking in terms of the former makes women and their disadvantage the problem and hides the way that we need to be addressing men’s unfair advantage as well.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.