We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

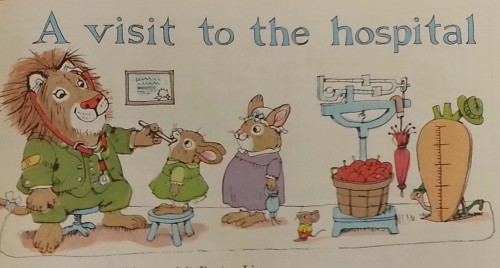

As children, many of us encountered Richard Scarry’s book, What Do People Do all Day? A classic kid’s book, it uses animals to represent the division of labor that exists in “Busytown.” The book is an example of a brilliant piece of analysis by sociologist John Levi Martin.

To oversimplify greatly: Martin analyzes nearly 300 children’s books and finds that there is a marked tendency for these texts to represent certain animals in particular kinds of jobs. Jobs that allow the occupant to exercise authority over others tend to be held by predatory animals (especially foxes), but never by “lower” animals (mice or pigs).

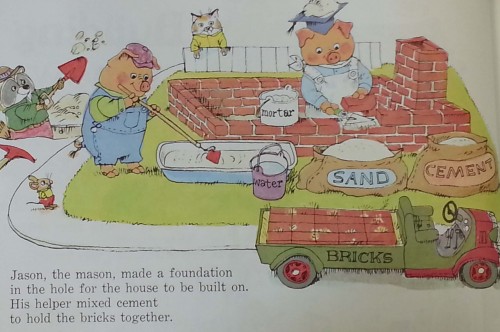

Pigs in particular are substantially over-represented in subordinate jobs (those with low skill and no authority), where their overweight bodies and (judging from the plots of these books) congenital stupidity seems to “naturally” equip them for subservient jobs. Here, see this additional image from Scarry’s book, showing construction work being performed by the above-mentioned swine.

In effect, Martin’s point is that there is a hidden language or code inscribed in children’s books, which teaches kids to view inequalities within the division of labor as a “natural” fact of life — that is, as a reflection of the inherent characteristics of the workers themselves. Young readers learn (without realizing it, of course) that some species-beings are simply better equipped to hold manual or service jobs, while other creatures ought to be professionals. Once this code is acquired by pre-school children, he suggests, it becomes exceedingly difficult to unlearn. As adults, then, we are already predisposed to accept the hierarchical, caste-based system of labor that characterizes the American workplace.

Steven Vallas is a professor of sociology at Northeastern University. He specializes in the sociology of work and employment. His most recent book, Work: A Critique, offers an overview and discussion of the sociological literatures on the topic. You can follow Steven at the blog Work in Progress.

Cross-posted at Work in Progress.