On October 28th, Miami Dolphins offensive lineman Jonathan Martin left the National Football League citing emotional distress as a result of abuse at the hands of his teammate Richie Incognito. Incognito admits to having sent Martin racist, homophobic, and threatening text messages and voicemails but argues that rather than hazing or bullying, this was merely an instance of miscommunication between the two men.

While a great deal of media attention has questioned the behavior of Richie Incognito, a disproportionate amount of attention has also been given to Martin’s choice to report the abuse. Why has Martin’s choice to report the abuse received so much attention? What has been the main theme of those critiquing Martin’s choice? And, what does this discussion mean for our national discourse on bullying and hazing? The answers to these questions, I argue, are all linked to masculinity.

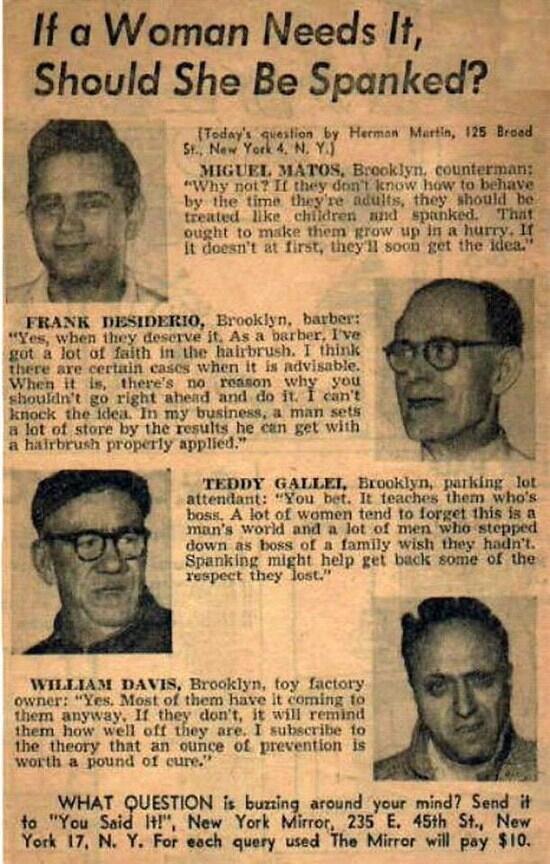

The media talks about Martin’s choice to report because his decision violated accepted cultural norms of masculinity. Some may call these norms, more colloquially, the “bro code,” “guy code,” or “man code.” Whatever we choose to call it, there are accepted ways in which men and boys are expected to conduct ourselves and our relationships to other men. Martin stands accused, especially within the athletic community, of having broken the code.

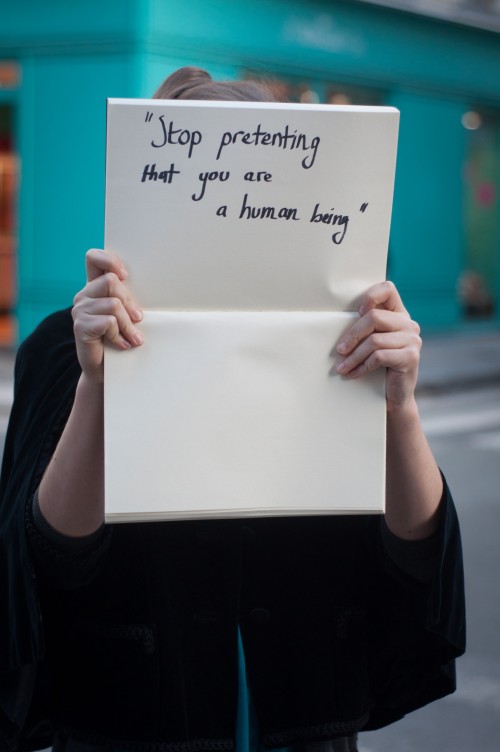

In a very telling interview, Channing Crowder, a former teammate of Incognito, made it clear that this conversation is really about masculinity. According to Crowder, Incognito tests his teammates. He “tests you to see if you have enough manhood or enough testosterone” (even though this type of bullying is just as much about the perpetrator’s masculinity as it is the victim’s).

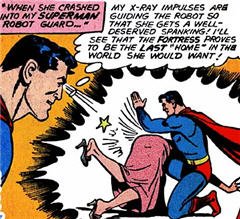

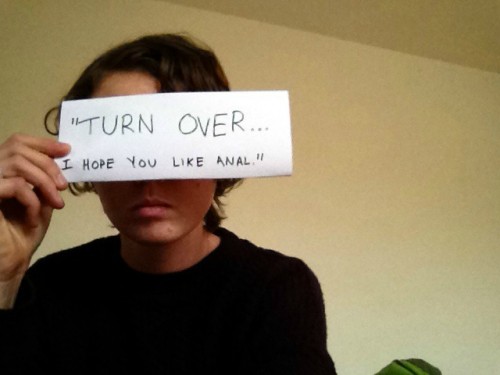

In this case Martin’s masculinity is under attack on two fronts. First, it is under attack because he failed Incognito’s “test” of his manhood. Second, he is under attack because his solution to Incognito’s bullying violated guy code. According to the code, real men solve their problems with one another through violence.

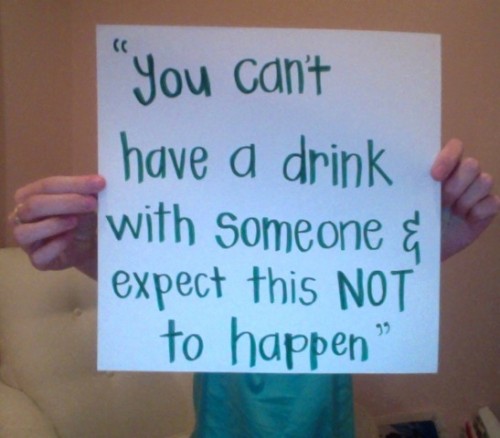

Sports Illustrated reported that many NFL personnel consider Martin to be a coward or a wimp for reporting the abuse. One NFL informant was even quoted saying “I think Jonathan Martin is a weak person. If Incognito did offend him racially, that’s something you have to handle as a man.” Others said it would have been preferable for Martin to “go down swinging” or to “fight.” Even NPR ran a piece in which a regular guest argued:

Martin should have taken that dude outside and put his lights out. I do not – I absolutely do not believe in a society where we run to the principal’s office every time these petty tyrants make a threat… Only power dispatches bullies… Jonathan Martin is a grown man and you can’t bully a grown man.

To be fair, in that same NPR piece, another interviewee stated that “not everybody resorts to violence in response to bullying and I applaud him for that.”

Nevertheless, by reporting the abuse rather than physically confronting Incognito, Jonathan Martin has been publicly stripped of his “man card.”

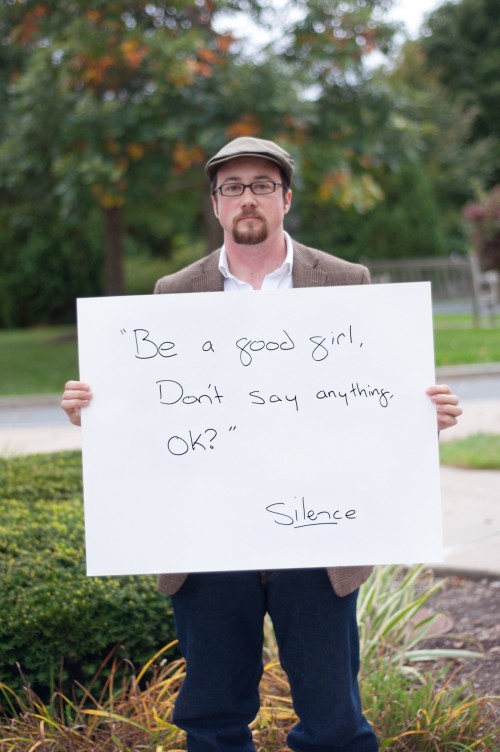

But, so what? Why should we care about how grown men address bullying? We should care because just as Jonathan Martin is being told to “man up,” so are young boys all over the country when they are bullied. Boys are told that when they cannot physically confront a bully they are inadequate and unworthy. They are taught to remain silent in the face of insurmountable violence because speaking out is a sign of weakness, or worse, femininity. Too many boys are left with nowhere to turn when bullying makes trauma a daily experience. In this sort of environment can we really be surprised that boys are committing suicide, developing depression, and lashing out violently at incredibly high rates?

Incognito on film:

Cliff Leek is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at Stony Brook University. He is a News Editor for Sociology Lens, co-founder of Masculinities 101, a Program Director for the Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities and a Research Assistant to TrueChild.

Cross-posted at Sociology Lens and The Good Men Project.