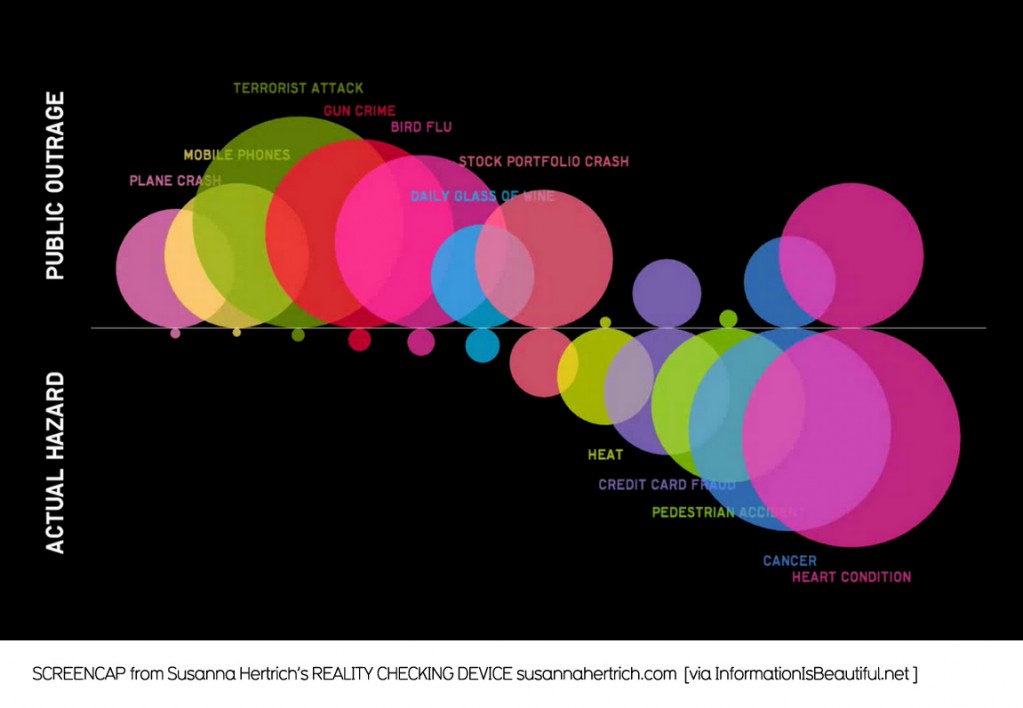

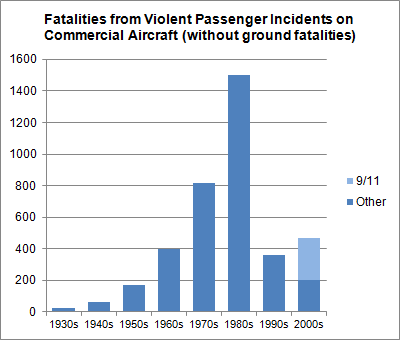

Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight posted some graphs that show a clear decrease in passenger deaths as a result of Violent Passenger Incidents (hijackings, sabotage/bombings, pilot shootings) since the 1980s:

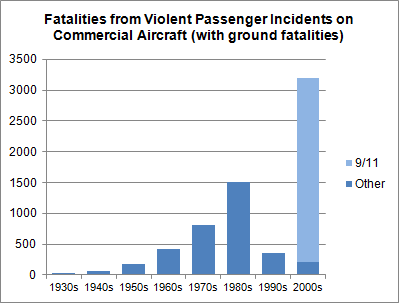

Of course, the vast majority of people killed on 9/11 weren’t in the planes, but on the ground; if you include those, then 2001 has a much higher fatality level than any other year:

Silver’s point is that because of 9/11 and attempted bombings since then, many people are under the impression that the danger of violent incidents on planes is increasing. But it clearly isn’t–the number of passengers killed per decade as a result of such incidents has gone down even as plane travel has become more widespread and the number of people in the air each year has increased.

He also suggests,

…the loss of life that occurred on the ground on 9/11 would be very hard for Al Qaeda or any other terrorist group to replicate. The reason is that the last line of defense against the terrorists has also proven to be the best, and that is the passengers. Brave passengers thwarted the hijacking attempts aboard United 93 and Qantas 173, and sabotage attempts aboard NWA 253 and AA 63 (the Shoe Bomber incident).

This isn’t, obviously, meant to say that we shouldn’t worry about airline security or that the loss of life on 9/11 is unimportant. It’s just a good example of how it can be difficult to judge whether the risk of things is increasing or decreasing, particularly when they’re scary, and incidents that are actually quite rare can seem to be happening “all the time” once we’re thinking about, and noticing reports of, them.