Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

I don’t know much about game theory. I’ve always found it hard to squeeze real-life situations into the shape of a prisoner’s-dilemma matrix and to think of life as a game. A game show, on the other hand, is a game. And the final round of the British show “Golden Balls” is totally Prisoner’s Dilemma. (Shouldn’t that apostrophe be moved to make it be Prisoners’ Dilemma? After all, it’s not solitaire.)

You can get the idea of the set-up in the first two minutes of this clip.* But don’t stop there. Watch the full six minutes, and appreciate the ingenuity of the strategy played by Nick (he’s the guy in the brown shirt on the right of the screen).

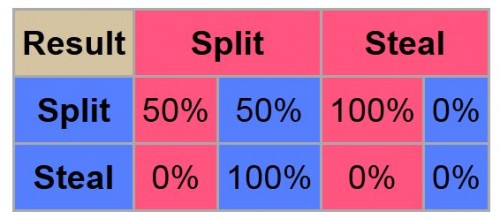

SPOILER SPACE, which I’ll fill with the “Golden Balls” matrix.

In many prisoner’s dilemma scenarios, the prisoners are separated and can’t discuss their options. In “Golden Balls,” they can talk things over, the only catch being that each player is well aware that the other might be lying. Earlier rounds of the game are designed to encourage lying.

Nick is ingenious in two ways. First, he brings in an option that “Golden Balls” does not include but cannot exclude: the offer to split the loot 50-50 after the show even if the show gives the entire amount to him.

Second (and here is where my lame game-theory knowledge is showing), by convincingly maintaining that he is going to Steal, he destroys the Nash equilibrium that “Golden Balls” tries to create. He forces Ibraham to choose Split, for Ibraham’s position now becomes this:

- If Nick is fully telling the truth about sharing: Split, I get £6500. Steal, I get 0.

- If Nick is lying about sharing: Split, I get 0. Steal, I get 0.

- So my only hope of getting anything is Split.

Which is what he does.

Nick’s ploy also creates an interesting dramatic switcheroo for the viewers as well. As we watch the clip, it looks as though all the pressure is on Ibraham. We can see him debating with himself and with Nick. But after the two men show their balls, we realize that in reality, it’s Nick who had to be sweating, not about which choice he will make – he has already decided that – but about whether he is actually fooling Ibraham. He was betting £13,000 on his own acting ability. That takes balls.

One other observation: I used to watch “Survivor,” and when players would lie and succeed, I might have admired them for being the clever strategist, but I didn’t like them. In fact, I often actively disliked them. But here, when I found that Nick had lied successfully, I was hoping that Ibraham or “Golden Balls” would give him a few extra pounds as a bonus.

* The clip is from February. I found it thanks to Planet Money, which posted it last week without comment.