The mass media often enjoys stoking the fires of the “nature/nurture debate,” an argument between those who believe that human behavior is largely inborn (nature) and those who believe it is largely learned (nurture). In fact, most scholars reject this forced choice in favor of the idea that nature and nurture are forces that shape each other.

In this view, biology is both an independent and a dependent variable. That is, it acts on us in ways that shape our interactions with others (such that behavior is dependent on biology) and our interactions with others shape our biology (such that our biology is dependent on our behavior). I’ve published professionally on this topic and we’ve previously posted examples involving the socio-genetic causation of psychopathy, the response of testosterone levels to political victories, and the historical shift in the average age of menstruation.

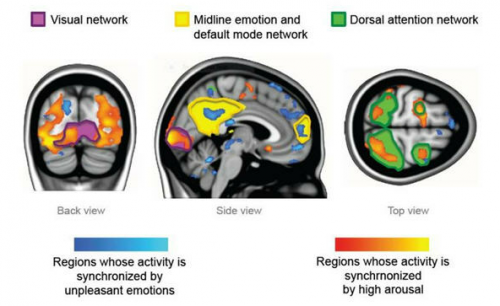

Today’s example comes from an fMRI study of emotion. They discovered that, when we watch others experience emotions, our brains sync up with theirs. Our bodies, in other words, strongly react to environmental stimuli. This, argues one of the researchers, “…facilitates understanding others’ intentions and actions… [as well as] social interaction and group processes.”

It may seem obvious that our neural activity would respond to our environments, but I think it bears emphasizing. It is too easy for us, in a society that seems eager for a biological explanation for everything, to ignore the ways in which the body is a dependent variable as well as an independent one. In many ways it makes sense to think of our biologies as the matter through which social interaction occurs. In other words, while we often think of society as the medium for the transmission of genes, I also like to think of biology as the medium for the transmission of society.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.