For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2011. Originally cross-posted at Jezebel and Owni.

————————

A few years ago my mom took a short-term nursing job at a hospital in the Sacramento area. This was a huge deal for her. She had never been to California, hadn’t lived outside of our rural area of Oklahoma since she divorced my dad when I was a baby, and had never worked at a “big city” hospital. She feared she wouldn’t be able to make it, that her rural hospital experience just wouldn’t translate. There were a lot of firsts for her, but it went well and the hospital administration told her they’d be happy to have her back. She was incredibly proud of herself, both for doing a good job and for being able to survive in California, a location trumped in the Big Scary Places sweepstakes only by New York City. It was an enormous confidence builder: she could leave her small town and she could make friends and keep a job.

And then, a few days before she was set to leave, she called me. Some of the staff had a little informal going-away party for her, and she was baffled by the card they’d all signed for her. It featured Jeff Foxworthy, the comic who made a name with his “You might be a redneck if…” schtick in the ’90s. The joke on the card was something about being a redneck if you used Hefty trash bags for luggage. But why, my mom asked hesitantly, would they give that to her? She’d never told them she liked Jeff Foxworthy; what made them think she’d want a card with him on it? And finally, in a plaintive voice that still just breaks my heart when I remember it, she asked me if it was possible they were implying she is a redneck, and that the people she thought were her friends were laughing at her.

Of course they did, and were. That doesn’t mean they didn’t genuinely like her or didn’t think she’s an excellent nurse, or that they meant to be hurtful; they probably assumed she’d get the joke, what with her accent, unusual colloquialisms, and openly-expressed awe and complete lack of irony or cynicism. But in fact, the idea that her new friends might view her as a redneck or a hick was a shock. She didn’t know what she might have done that would make other people think she’s a redneck. And I could tell she was terrified — afraid that instead of “making it” in California, she was actually a joke, and too clueless to know it.

I lied to her. I said I was sure it wasn’t anything specific to her, but was just because she was from Oklahoma, and Jeff Foxworthy is from the South, so they probably just thought everybody in the South or South-adjacent region likes him. I knew it would break her heart and totally destroy her new-found confidence to think that to a lot of people, she represented stereotypes of backward rednecks, not the hard-working medical professional she’d been working so hard to portray herself as.

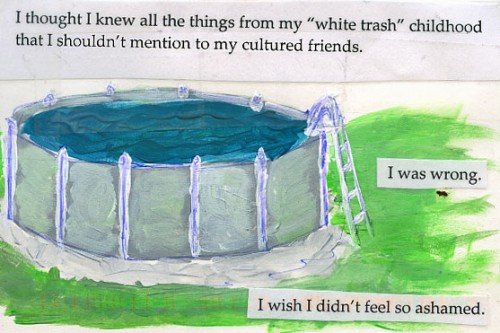

I thought of that experience when I saw this postcard from Post Secret:

I’ve built up a lot more cultural capital than my mom, going to grad school and being socialized into the norms of academia. I mostly eradicated my accent when I was an undergrad, I figured out that Velveeta cheese was not an acceptable addition to a cheese plate at an upper-middle-class dinner party, and I learned that most people don’t view skunks, squirrels, opossums, or raccoons as animals you might potentially turn into pets, if you’re brave and really dedicated.

I don’t feel ashamed of my background any more, because I’ve achieved enough proof of upper-middle-class success — a Ph.D., a tenure-track job, the knowledge that Brie is fancy cheese and not, as my grandma thought upon seeing it for the first time, fish bait — and some useful theories, like the idea of cultural capital, to help me make sense of what’s going on.

But I recognize the sentiment expressed in the postcard — the ever-present possibility that you’ll un-self-consciously mention something from your childhood and be met with gleefully horrified looks and giggles, and not know what’s so funny about shrugging and off-handedly saying, “I don’t know if I really need to see a movie about it, I’ve watched my relatives do it tons of times” when someone suggests watching the documentary Okie Noodling. It’s an extra little mental effort you have to expend as you navigate social encounters, trying to imagine whether something as small as honestly answering a simple question like what was your favorite food when you were a kid might open you up to ridicule. It’s not really the laughing itself, which is often good-natured and comes from people who do honestly like you, that’s so bothersome; it’s the realization that you still don’t know the cultural rules, and thus can’t necessarily protect yourself from being laughed at even if you wanted to — or in my mom’s case, that you don’t know what it is you’re doing that makes you a redneck in other people’s eyes.