In the late 1940s and 1950s, sex researcher Alfred Kinsey estimated that about 10% of the population was something other than straight (and then, as now, a much larger number have same sex experiences or attraction). Today scholars believe that about 3.5% of the U.S. population identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual, a considerably lower number. Yet, a telling poll by Gallup shows that Americans wildly — wildly — overestimate the number of people who identify as non-heterosexual:

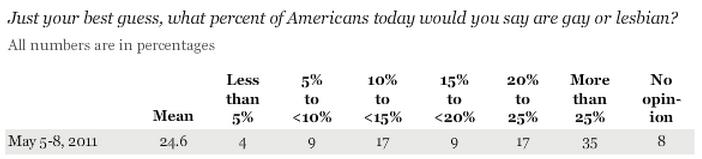

The table shows that more than a third of Americans believe that more than one out of every four people identifies as gay or lesbian. Only 4% of Americans answered “less than 5%,” the correct answer.

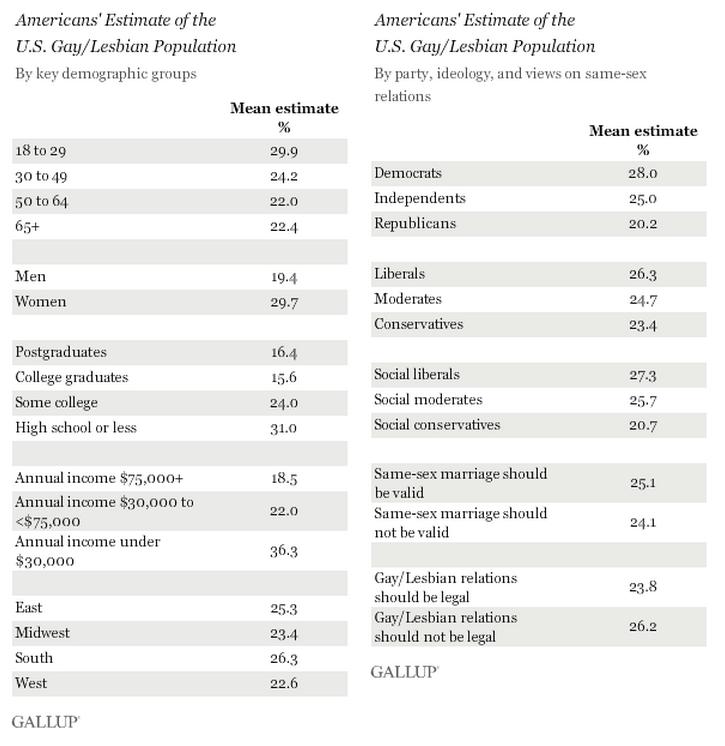

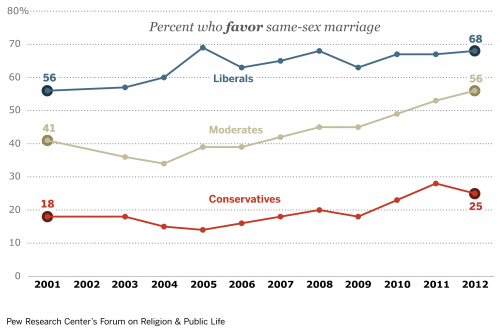

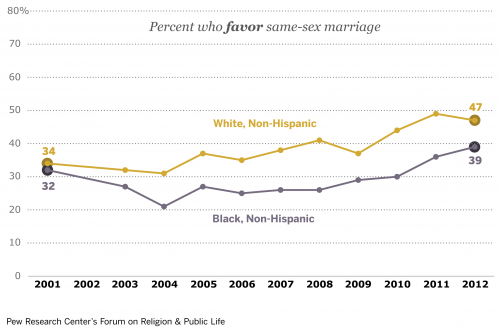

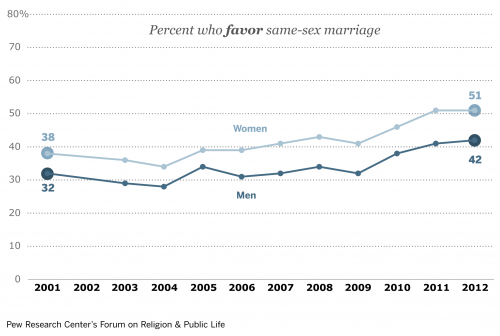

Estimates varied by demographics and political leaning. Liberals were more likely to overestimate, as were younger people, women, Southerners, and people with less education and income:

Interestingly, these numbers are higher than in 2008, when Gallup asked a similar questions. In that poll, only a quarter of the respondents choose “more than 25%” and more than twice as many said that they had “no opinion.”

Gallup concludes: “…it is clear that America’s gay population — no matter the size — is becoming a larger part of America’s mainstream consciousness.”

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.