Part of what makes professional basketball appealing, for kids who love to play as well as fans, is the idea that a person can come from humble beginnings and become a star. The players on the court, the narrative goes, are ones who rose to fame as a result of incredible dedication and extraordinary talent. Basketball, then, is a way out of poverty, a true equal opportunity sport that affirms what we think America is all about.

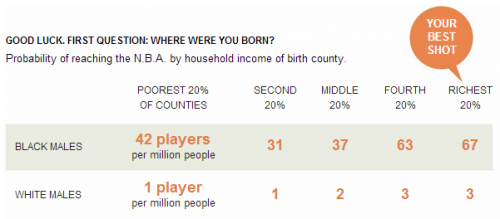

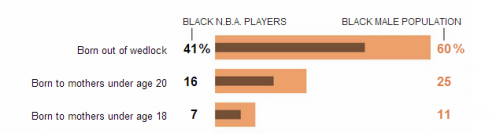

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz crunched the numbers to find out if the equal opportunity story was true. Analyzing the economic background of NBA players, he found that growing up in a wealthy neighborhood (the top 40% of household incomes) is a “major, positive predictor” for success in professional basketball. Black players are also less likely than the general black male population to have been born to a young or single mother. So, class privilege is an advantage for pro ball players, just like it is elsewhere in our economy.

.

The richest Black men, then, are most likely to end up in the NBA, followed by those in the bottom 20% of neighborhoods by income. Middle class black men may, like many middle class white men, see college as a more secure route to a successful future. Research shows that poor black men often see sports as a more realistic route out of poverty than college (and they may not be wrong). This also helps explain why Jews dominated professional basketball in the first half of the 1900s.

LeBron James was right, then, when he said, “I’m LeBron James. From Akron, Ohio. From the inner city. I am not even supposed to be here.” The final phrase disrupts our mythology about professional basketball: that being poor isn’t an obstacle if one has talent and drive. But, as Stephens-Davidowitz reminds us, “[a]nyone from a difficult environment, no matter his athletic prowess, has the odds stacked against him.”

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.