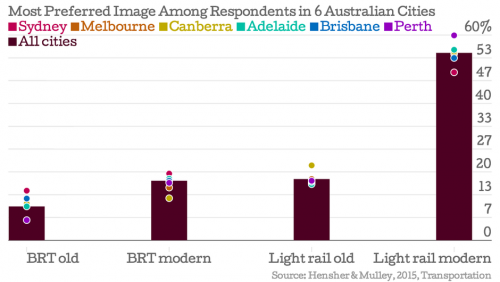

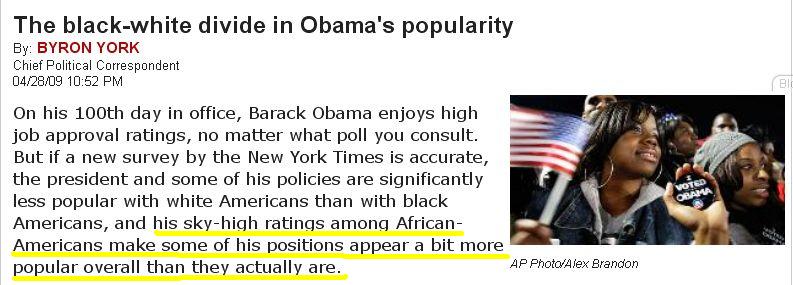

Look closely. Which would you rather ride?

Transport scholars David Hensher and Corinne Mulley asked this question of residents of six cities in Australia. They included these ultra modern examples and also photographs featuring less modern trains and buses.

They found that people overwhelmingly preferred trains to buses, even though the modern bus has a dedicated lane just like the train and identical boarding and fare collection procedures.

We associate trains with romance and leisure travel or hip, urban places like Manhattan. In contrast, buses bring to mind traffic, exhaust, and being exhausted after getting off from a second job. Members of a focus group organized by the U.S. Department of Transportation, for example, had these things to say:

I’m ashamed to tell that I am taking buses…In Europe, I wouldn’t. But here, they would think, “Did he lose his job?”

The shame factor is majorly big.

I’m just saying that when I was in L.A. and I was in the car and just looking in at the bus…the people getting on….it just seems scary…

The bus has a bad rap.

But the authors found it wasn’t that simple. People from cities with better bus service tended to feel a little better about buses. If someone had recently had a good experience on a bus — like getting a seat for the whole trip — they felt better about buses. In fact, riding buses made people like buses more. People who rode more often had a better opinion.

Basically, give people good buses, good bus routes, and good service and they will come to love buses.

So, the authors argue that cities shouldn’t let the bad reputation of buses stop them from providing and improving bus service. Often buses are a better choice than trains. Bus routes are cheaper to get started and easier to change. High frequency and dedicated lanes can make them as efficient. So, if a bus is the right thing for the city, don’t give the people what they want, show them.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.