Who believes that the climate is changing? Researchers at Yale’s Project on Climate Change Communication asked 13,000 people and they found some pretty interesting stuff. First, they found that there was a great deal of disagreement, identifying six types:

- The Alarmed (18%) – believe climate change is happening, have already changed their behavior, and are ready to get out there and try to save the world

- The Concerned (33%) – believe it’s happening, but think it’s far off or isn’t going to affect them personally

- The Cautious (19%) – aren’t sure if it’s happening or not and are also unsure whether it’s human caused

- The Disengaged (12%) – have heard the phrase “climate change,” but couldn’t tell you the first thing about it

- The Doubtful (11%) – are skeptical that it’s happening and, if it is, they don’t think it’s a problem and don’t think it’s human caused

- The Dismissive (7%) – do not believe in it, think it’s a hoax

As you might imagine, attitudes about climate change vary significantly by state and county. You can see all the data at their interactive map. Here are some of the findings I thought were interesting.

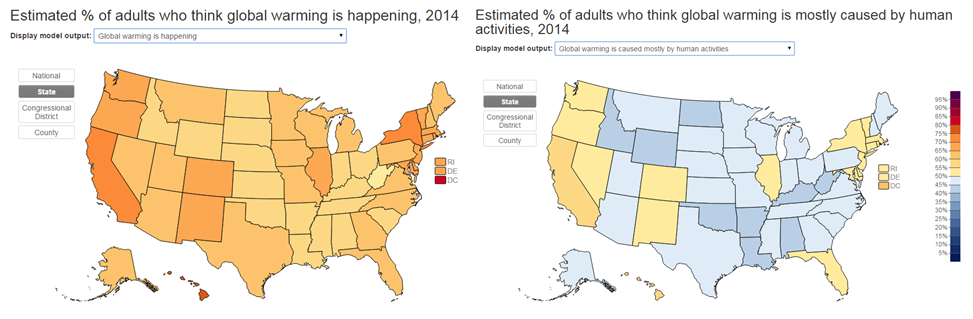

More Americans think that climate change is happening (left) than think it’s human caused (right); bluer = more skeptical, redder = more believing:

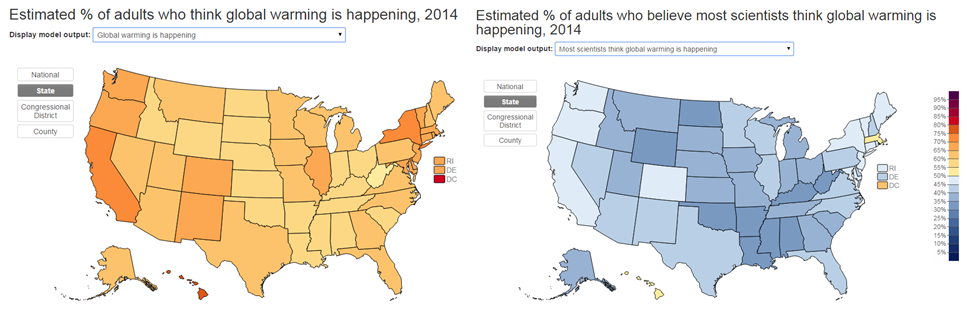

Even among people who say that they personally believe in climate change (left, same as above), there are many who think that there is no scientific consensus (right) suggesting that the campaign to misrepresent scientific opinion by covering “both sides” was successful:

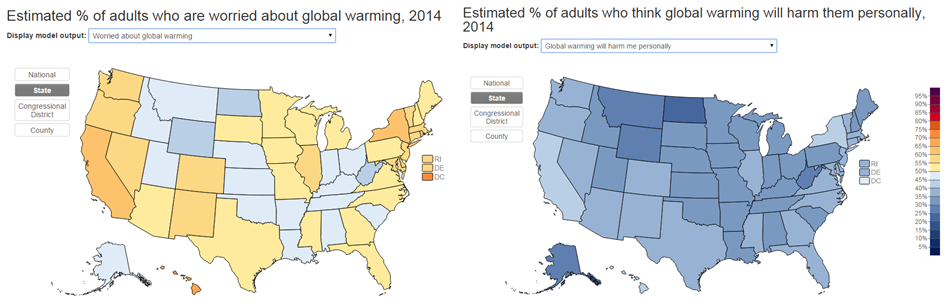

People are somewhat worried about climate change (left), but very, very few think that it’s going to harm them personally (right):

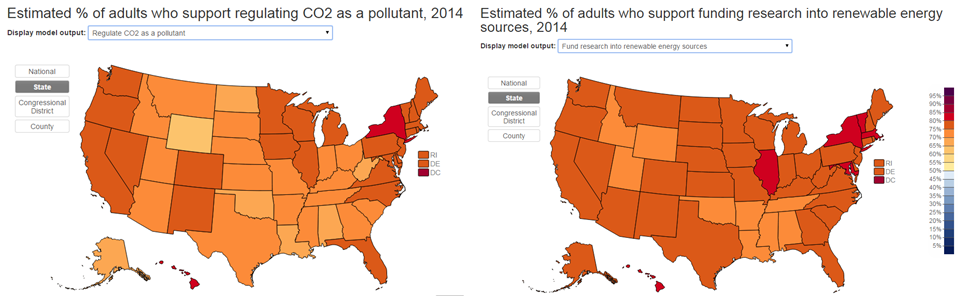

Even though people are lukewarm on whether it’s happening, whether it’s human-caused, and whether it’s going to do any harm, there’s a lot of support for doing something about it. Support for regulating CO2 (left) and support for funding research on renewable energy (right):

Take a closer look yourself and explore more questions at the map or read more at the Scholars Strategy Network. And thanks to the people at Yale funding and doing this important work.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.