Ben O. sent us these three images. This image (found here) is of a sticker on the window of a car (presumably a Mustang?) that says “Built with tools, not chopsticks.” The car is, ironically, parked in front of a sushi bar (see the reflection in the window).

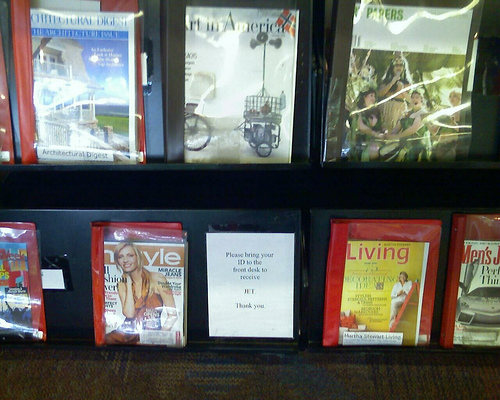

These next two images (found here and here) illustrate how this particular public library requires an ID to look at both Jet and Essence (magazines aimed at Black Americans), but not other magazines. Presumably, someone thinks that magazines consumed by Black Americans are more likely to be stolen than other magazines. Ben asks:

Is this racism? Is this censorship? What do you think about it?

Thanks Ben!

NOTE: In the comments, several readers questions whether the last image is an example of everyday racism. Yes, magazines are sometimes kept at the circulation desk because they are perceived to be at high risk of being defaced or stolen, but they’re also sometimes kept behind the desk if they’re highly popular, to prevent patrons from monopolozing them for very long periods of time. By forcing patrons to check them out rather than have them freely available on the shelves, patrons can keep them for only a cetain length of time, guaranteeing that other patrons who might wish to read them also have an opportunity. So it’s possible that Jet and Essence are kept behind the counter because they are very popular titles and the library is trying to be sure as many patrons as possible get access to them. So this image might be better used to talk about the difficulties that can arise interpreting situations where race appears that it might be playing a part, but it isn’t clear whether it is or in what way.