Sorry for the sporadic posting. I’m visiting family in Oklahoma and that means very, very limited internet access.

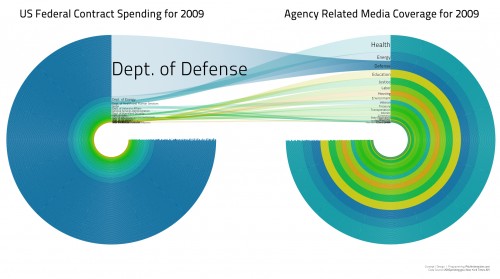

Zac from Georgia sent in a link to some interesting images that illustrate the mismatch between what the federal government spends money on and what the media cover. This image shows spending only via federal contracts (not all spending) compared to all articles in the New York Times in 2009 (granted, a very small sample of all media coverage, so keep that in mind):

Contract spending data is available here.

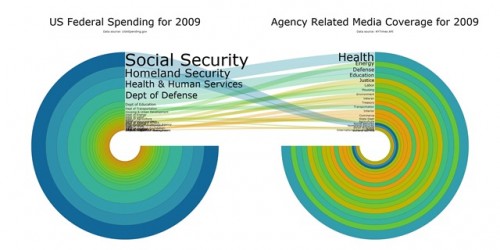

This time we have all spending, not just spending through contracts; the Department of Defense has dropped down to 4th place:

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.