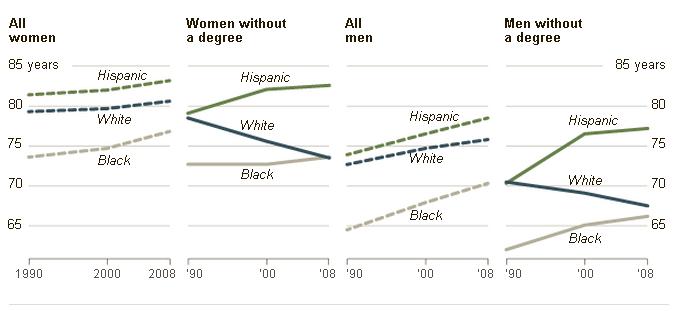

The New York Times‘ Sabrina Tavernise reports that the long term trend of increasing life expectancy has reversed it self among one specific group of people. Between 1990 and 2008, the life expectancy of White men and women without high school degrees has dropped. Women have lost five years, men three.

The difference in the life expectancy between men and women without high school degrees and those who complete college are even more striking. Women with a college degree can expect to live, on average, more than 10 years longer than high school drop outs. Among men, the gap is even larger, a whopping 13 years.

The words “alarming” and “vexing” were used to describe this drop in life expectancy. Scholars are still unsure of its causes, but note the stress of balancing work and family, “a spike in prescription drug overdoses among young whites, higher rates of smoking among less educated white women, rising obesity, and a steady increase in the number of the least educated Americans who lack health insurance.”

Ultimately, they argue, as fewer and fewer people fail to graduate from high school, the concentration of disadvantages in those that do are making this population especially vulnerable to all kinds of ills, some of which kill them.

Hat tip to The Global Sociology Blog.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.