Sociologists like to say that gender identities are socially constructed. That just means that what it is, and what it means, to be male or female is at least partly the outcome of social interaction between people – visible through the rules, attitudes, media, or ideals in the social world.

And that process sometimes involves constructing people’s bodies physically as well. And in today’s high-intensity parenting, in which gender plays a big part, this includes constructing – or at least tinkering with – the bodies of children.

Today’s example: braces. In my Google image search for “child with braces,” the first 100 images yielded about 75 girls.

Why so many girls braced for beauty? More girls than boys want braces, and more parents of girls want their kids to have them, even though girls’ teeth are no more crooked or misplaced than boys’. This is just one manifestation of the greater tendency to value appearance for girls and women more than for boys and men. But because braces are expensive, this is also tied up with social class, so that richer people are more likely to get their kids’ teeth straightened, and as a result richer girls are more likely to meet (and set) beauty standards.

Hard numbers on how many kids get braces are surprisingly hard to come by. However, the government’s medical expenditure survey shows that 17 percent of children ages 11-17 saw an orthodontist in the last year, which means the number getting braces at some point in their lives is higher than that. The numbers are rising, and girls are wearing most of hardware.

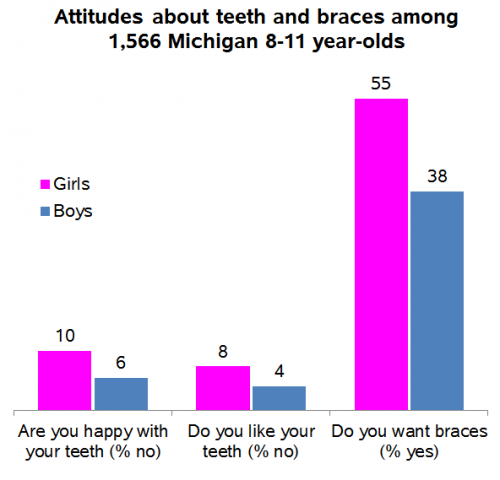

A study of Michigan public school students showed that although boys and girls had equal treatment needs (orthodontists have developed sophisticated tools for measuring this need, which everyone agrees is usually aesthetic), girls’ attitudes about their own teeth were quite different:

Clearly, braces are popular among American kids, with about half in this study saying they want them, but that sentiment is more common among girls, who are twice as likely as boys to say they don’t like their teeth.

This lines up with other studies that have shown girls want braces more at a given level of need, and they are more likely than boys to get orthodontic treatment after being referred to a specialist. Among those getting braces, there are more girls whose need is low or borderline. A study of 12-19 year-oldsgetting braces at a university clinic found 56 percent of the girls, compared with 47 percent of the boys, had “little need” for them on the aesthetic scale.

The same pattern is found in Germany, where 38 percent of girls versus 30 percent of boys ages 11-14 have braces, and in Britain – both countries where braces are covered by state health insurance if they are needed, but parents can pay for them if they aren’t.

Among American adults, women are also more likely to get braces, leading the way in the adult orthodontic trend. (Google “mother daughter braces” and you get mothers and daughters getting braces together; “father son braces” brings you to orthodontic practices run by father-son teams.)

Teeth and consequences

.

Today’s rich and famous people – at least the one whose faces we see a lot – usually have straight white teeth, and most people don’t get that way without some intervention. And lots of people get that.

Girls are held to a higher beauty standard and feel the pressure – from media, peers or parents – to get their teeth straightened. They want braces, and for good reason. Unfortunately, this subjects them to needless medical procedures and reinforces the over-valuing of appearance. However, it also shows one way that parents invest more in their girls, perhaps thinking they need to prepare them for successful careers and relationships by spending more on their looks.

When they’re grown up, of course, women get a lot more cosmetic surgery than men do – 87 percent of all surgical procedures, and 94% of Botox-type procedures – and that gap is growing over time.

As is the case with lots of cosmetic procedures, people from wealthier families generally are less likely to need braces but more likely to get them. But add this to the gender pattern, and what emerges is a system in which richer girls (voluntarily or not) and their parents set the standard for beauty – and then reap the rewards (as well as harms) of reaching it.

Cross-posted at Family Inequality, Adios Barbie, and Jezebel.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.