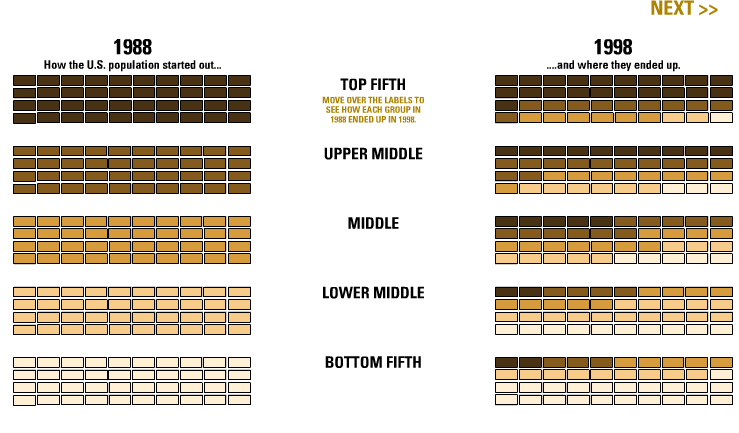

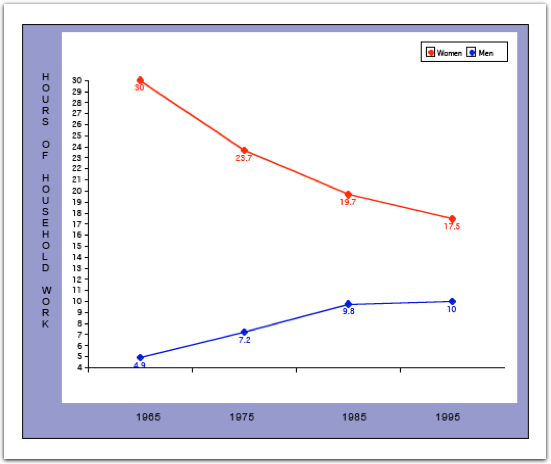

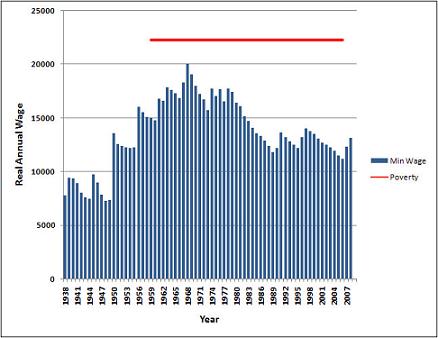

Ed at Gin and Tacos offered up the figure below comparing the minimum wage (adjusted to inflation) and the poverty line for a family (he doesn’t specify how many children). It reveals that, as Ed puts it: “not once in its 80-year history has the minimum wage, if earned 40 hours weekly, hit the Federal poverty line for a family.” That is, a dedicated full time worker earning minimum wage does not earn, and has never earned, enough to keep a family out of poverty.

So, if you are a single parent, you’re screwed. (And, frankly, if you aren’t, you’re still screwed because child care will likely wipe out, if not exceed one person’s entire income. Subsidized day care only serves a fraction of the children that are qualified.)

Ed notes that, given this, the rational choice for a parent is to go on welfare. Welfare doesn’t get you above the poverty line either, and you’re still likely to be miserable, but at least you’ll be miserable while parenting your children instead of miserable while flipping burgers.

Some argue that, if people choose to go on welfare instead of work, then welfare must be too generous. Lower welfare payments and people will choose to work. Ed, however, suggests that the real problem revealed by this figure is the insufficiency of the minimum wage. Raise the minimum wage and people will choose to work. Only one of these solutions actually mitigates human suffering.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.