Originally posted in 2009. Re-posted in honor of Women’s History Month.

I still remember when the female characters on the sitcom Friends started the trend of visible nipples:

As long as I’d been alive and paying attention, hard nipples were embarrassing. Then, suddenly, they weren’t. I even remember hearing that women could get the all-hard-all-the-time look by buying those tiny rubber bands (that I only associate with the plastic bags aquarium fish come in) and fitting them tightly around your nipples. Nipples are still big, if measured by mannequins (Wicked Anomie noticed too).

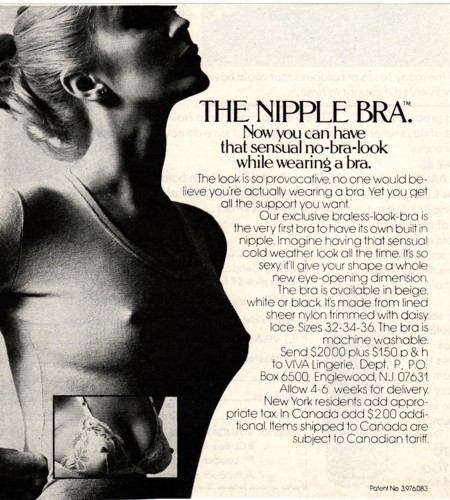

It turns out this comes in fits and starts. This vintage ad (no date on the source), for example, features a bra with built-in hard nipples! (Apparently it had been a trend before I’d been alive and paying attention.)

In the comments, Dmitriy T.C. added a link to the patent for this device. I can’t resist adding this particular paragraph explaining why a bra with fake nipples is important:

…simulated nipples for a brassiere would offer an acceptable compromise for ladies who do not wish to go without a brassiere and a welcome release from the subconscious effects of the suppression brought on by wearing brassieres of the types variously available, which obliterate the nipple.

LOL.

Anyhow, Tracey at Unapologetically Female wondered about wearing such a bra:

Didn’t anyone ever start to wonder why these women’s nipples were ALWAYS hard? And what if their real nipples (realistically probably located somewhere a bit lower than the bra’s) ever poked through, creating a quadruple effect?! Horrifying.

I find this whole thing especially funny, since, while shopping recently, Katie and I were making fun of these bras with built-in “modesty panels” that provide extra padding so that the nipple will never make an appearance. Times sure have changed.

Except times haven’t changed in the sense that women’s bodies still aren’t allowed to just be. Their nipples either must show, or must not show, or they should show in some contexts, or are allowed to show, but in other contexts they better not show. (Remember the outcry over Hilary Clinton’s “cleavage”? Can you imagine if she’d shown some nip!?)

So apparently we’re supposed to have nipple bras, bras with “modesty panels,” and a couple rubber bands in our pockets just in case. The one thing that is clearly less than ideal in all this: actual nipples doing what they do.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.