Well, folks, we’ve gotten enough submissions of gendered products that I decided it’s time for another round-up. To start off, way back in February Annie J., a librarian from Vancouver, sent us this ad she saw in a mall in Surrey, British Columbia, for Movado watches. The ad labels the man’s and woman’s watches with the characteristics supposedly appropriate for their wearers:

The bolded text for the man’s watch: man of many interests, manages risks, is strong and dependable, remains flexible, always has your back. Bolded text for the woman’s watch: a contemporary woman, loves a bit if mystery, knows exactly what she wants, craves a touch of luxury, gets what really matters.

From Carrie Brennan, we get a pair of gendered klompen, which were seen at Zandse Zaanse Schans, in the Netherlands:

The pink ones are emblazoned with the word lief, which translates as sweet or lovable; stoer, written on the blue ones, means tough or sturdy.

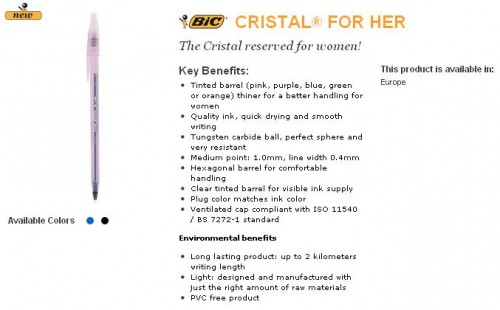

For all the women out there who have struggled with big ole regular-sized pens, you may be happy to know (via Dmitriy T.M., Monica C., and Katrin) that BIC has introduced a pen just for us! The BIC Cristal for Her, which is “reserved for women,” is thinner than regular pens so we can handle them better:

If the website is correct regarding availability, since I do not live in Europe, I must sadly muddle along with my giant, over-sized pen. Alas!

But there’s more! Maybe you’ve been needing a wrist brace, but you worry that it’ll make your wrist look bulky. Fear not! Lauren K. came across women-specific wrist braces:

As she explains at her blog, Diary of a Messy Lady, it promises a “slim silhouette” and has a “contoured fit tailored to the natural curves of a woman’s wrist and arm.” Because the definite distinction here is between men’s and women’s arms; in no way would it make sense that the major distinction might be, say “small” and “large” or something.

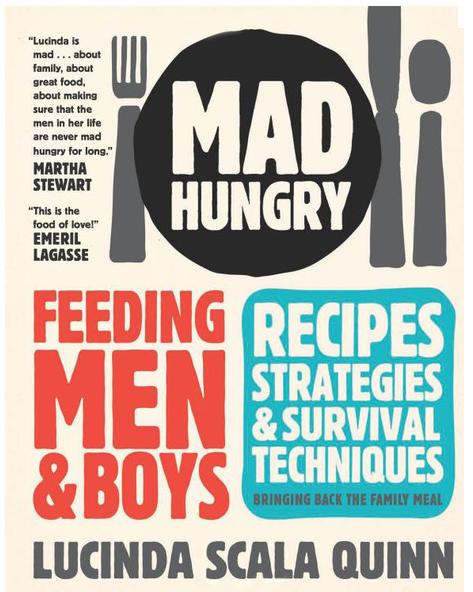

Another reader sent in a link to a truly essential cookbook, Mad Hungry: Feeding Men and Boys: Recipes, Strategies, & Survival Techniques: Bringing Back the Family Meal, by Lucinda Scala Quinn:

According to the description on Amazon, the book includes “…winning strategies for how to sate the seemingly insatiable, trade food for talk, and get men to manage in the kitchen.” It is a relief to finally have a cookbook that specifically explains how to feed men and boys, since up until now men and boys have largely gone hungry, with no one cooking them meals and regular cookbooks including recipes that only women and girls could digest. And how super awesome if, in return for being cooked just the right thing, a guy will “trade” some conversation with you!

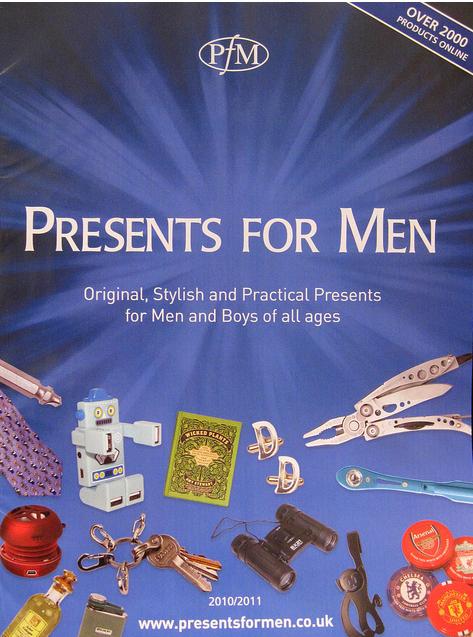

David M. is a member of Historic Scotland, an organization that maintains a number of historic sites throughout Scotland. As a member, he receives a copy of their magazine. A while back, it came bundled with a catalog (posted at Flickr by Wish I Were Baking):

It’s for the website Presents for Men, a website dedicated to stocking a wide array of things it defines as male-specific, though there’s also a “gifts for girls” section. David was less than flattered by their perceptions of the preferences of men these days. Scrotum-shaped golf-ball holder, anyone?

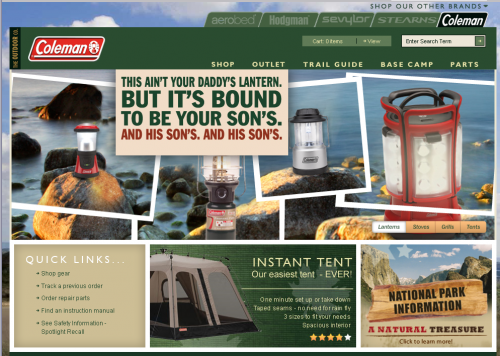

Back in August, Helen L. went to the Coleman website to look at camping gear. She was greeted with a pop-up that made clear, in no uncertain terms, who they expect to be using, and inheriting, their lanterns:

Chelsea N. saw some laxatives just for women available at Rite Aid; other than being pink, it’s unclear what is gyno-specific about them:

In another case of truly pointless gendering, Grace W. was at Target shopping for body scrubbers; they may look to you like anyone could use them, but the tag under the bin said otherwise:

There were none at all available for men, sadly.

Finally, Jordan J. sent in an image of two onesies, previously available from Gymboree. Your options? You can be “smart like dad” or “pretty like mommy”:

They’re either sold out or they’ve been removed from the website.