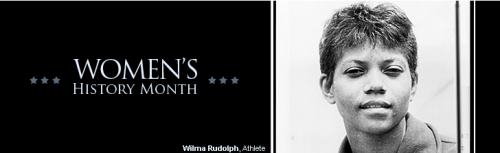

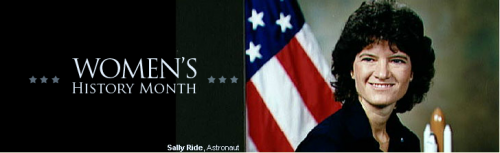

Amelia Earhart, aviator. Wilma Rudolph, athlete. Sally Ride, astronaut. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, activist. Josephine Baker, performer. Virginia Woolf, novelist. Rosie the Riveter, archetype. Alice Paul, suffragist. Frida Kahlo, artist. Hillary Clinton, Secretary of State.

Amelia Earhart, aviator. Wilma Rudolph, athlete. Sally Ride, astronaut. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, activist. Josephine Baker, performer. Virginia Woolf, novelist. Rosie the Riveter, archetype. Alice Paul, suffragist. Frida Kahlo, artist. Hillary Clinton, Secretary of State.

What do these women have in common? They are the 10 iconic women featured this year by womenshistorymonth.gov, the official website of Women’s History Month in the United States. A rotating banner across the top of the page shows a photo of each woman, her name, and a one word description, presumably the reason she is worthy of celebration.

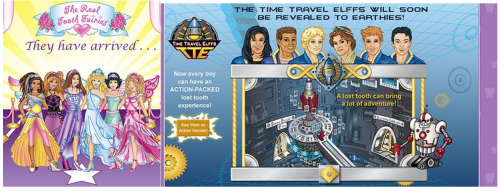

Unfortunately, the women singled out for recognition at the site appear to be considered notable mainly because they excelled at what are generally thought to be “masculine” pursuits. This is androcentric, meaning that it values masculinity over femininity. Traits that have been traditionally conceptualized as masculine (such as being a leader and good at sports and math) are now seen as valuable for girls to develop, while boys are often still discouraged from do things traditionally conceptualized as feminine (such as nurturing, cooking, and cleaning).

I am all for questioning the idea that certain jobs are “men’s jobs,” but we also need to challenge the idea that only women can do “women’s jobs.” If we do not, the belief that women should do “women’s work” and, more importantly, that women’s work is not worth celebrating, is left unquestioned.

Women’s History Month tends to follow this trend. None of the women we typically recognize at this time of year, for example, are noted for being good cooks, care givers, or educators of children, nor are they lauded for their nurturing of others, emotional openness, kindness, or compassion — all traditionally “feminine” traits. Caring for others and teaching youth are wonderful things that everyone should be encouraged to do. Our history books should be filled with people of all genders who were exceptional in these areas. But, these traditionally feminine pursuits are not what earns one accolades during Women’s History Month, or any other time. As a consequence, people are not taught to value such jobs or the people who do them. This one-sided celebration is unlikely to solve the very problem that Women’s History Month is ostensibly designed to combat: gender inequality.

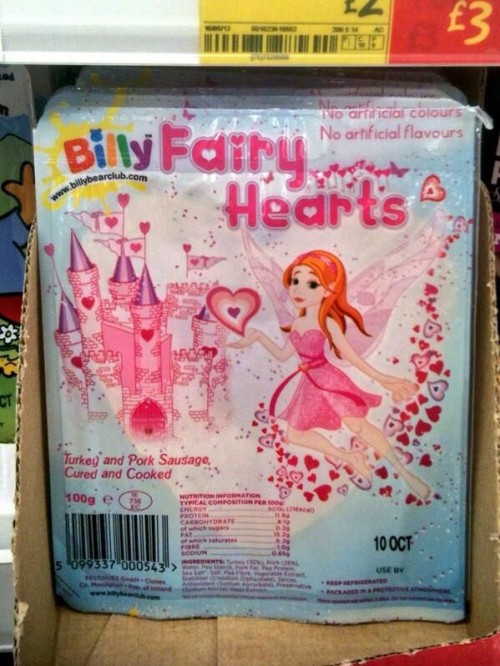

“To all the women who quietly made history” (source):

Laurel Westbrook is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Grand Valley State University. Her research focuses on gendered violence, social movements, and the inner workings of the sex/gender/sexuality system.