Until as late as the 1950s, there was no widely accepted set of terms that referred to whether people were attracted to the same or the other sex. Same-sex sexual activity happened, and people knew that, but it was thought of as a behavior, not an identity. It was believed that people had sex with same-sex others not because they were constitutionally different, but because they gave in to an urge they were supposed to resist. People who never indulged homosexual desires weren’t considered straight; they were simply morally upright.

Today our sexual object choices are generally believed to reflect more than a feeling; they are part of who we are: as a static, essential identity, one that it inborn and unchanging. And we have a plethora of language to describe one’s “sexual orientation”: asexual, heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, polysexual, demisexual, and more. It has been, as Michel Foucault put it, “a multiplication of sexualities.”

Undoubtedly, this has value. These words, for example, give a name to feelings that have in recent history been difficult to understand. They also enable sexual minorities to find community and organize. If they can come together under the same label, they can join together for self-care and the promotion of social change.

These labels, though — and the belief in sexual orientation as an identity instead of just a behavior — also create their own voids of possibility. It’s significantly less possible today, for example, for a person to feel sexual urges for someone unexpected and dismiss them as irrelevant to their essential self. Because sexual orientation is an identity, those feelings jump start an identity crisis. If a person has those feelings, it’s difficult these days to shrug them off (but see Not Gay: Sex Between Straight White Men). Once one comes to embrace an identity, then all sexual urges that conflict with it must be repressed or explained away, lest the person undergo yet another identity crisis that results in yet another label.

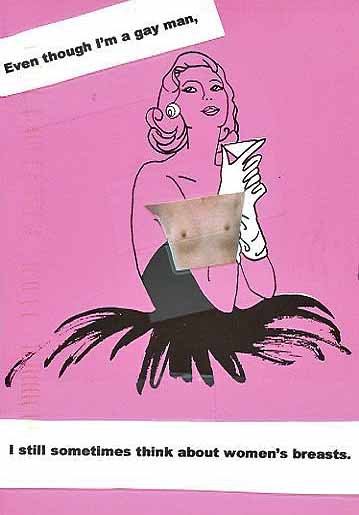

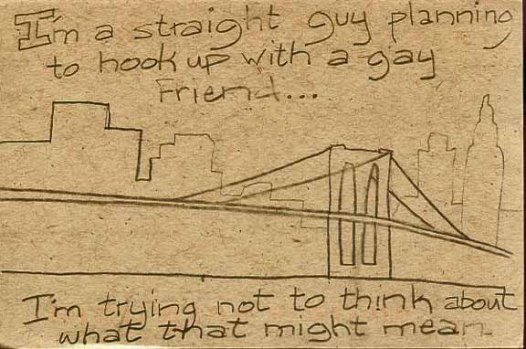

This train of thought was inspired by these anonymous secrets sent into the Post Secret project:

.

“Even though I’m a gay man,” the first confessor says, “I still sometimes think about women’s breasts.” I AM, he says, a GAY MAN. It is something he is, essential and unchanging. Yet he has a feeling that doesn’t obey his identity: an interest in women’s breasts. So, “even though” he is gay, he finds himself distracted by something about the female body. It is a conundrum, a identity problem, even a secret that he perhaps confesses only anonymously. To be open about it would be to call into question who he and others think he is, to embark on a crisis. “I’m trying not to think about what that might mean,” says the other.

But none of this is at all necessary. It is only because we’ve decided that our sexual urges should be translated into an identity that thinking about women’s breasts seems incompatible with a primary orientation toward men. In a world of no labels at all, one in which sexual orientation is not an idea that we acknowledge, people’s sexual urges would be nothing more than that. And if that world was free of homophobia and heterocentrism, then we would act or not act on whichever urges we felt as we wished. It wouldn’t be a thing.

Most people think that the multiplication of sexualities is a good thing. From this point of view, language that can describe our urges, however imperfectly, makes those urges more visible and normalized, especially if we can make a case that they are inborn and unchanging, just a part of who we are. I don’t disagree.

But I see advantages, too, to a different system in which we don’t use any labels at all, where the object of one’s sexual attraction is an irrelevant detail or, at least, just one of the many, many, many things that come together to make someone sexy to us. In this world, we would be no more surprised to find ourselves attracted to a man one day and a woman the next than a construction worker one day and a lawyer the next, or a tall person one day and a short one the next, or an extrovert one day and an introvert the next. It would be just part of the messy, complicated, ever-shifting, works in mysterious ways thing that is the chemistry of sexual attraction. Nobody would have to have angst about it, seek support for it, defend it, or confess it as a secret. We would just… be.

Maybe the idea of sexual orientation was critical to the Gay Liberation movement’s goals of normalizing same-sex love and attraction, but I wonder if sexual liberation in the long run would be better served by abandoning the concept altogether. Perhaps a real sexual utopia doesn’t fetishize privilege genitals as the one true determinant of our sexualities. Maybe it simply puts them in their rightful place as tools for pleasure and reproduction, but not the end-all and be-all of who we are.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.