Originally posted at Scatterplot.

Olympic fever has hit! As we all marvel at the power, precision, and grace of the athletes, a more disturbing commentary has also emerged, one that diminishes women athletes’ accomplishments, defines them by the men around them, places them in tired tropes of sex objects, or infantilizes them as “girls.” Some journalists, in combination with a robust social media discussion, are calling this bad behavior out. But should we be so surprised?

According to past research, no. In our work, we see this as a more pervasive issue, and women’s collegiate coaching is a prime example. When Title IX was enacted in 1972 approximately 90% of women’s teams were coached by women; in 2014 that number dropped to 43%. Women comprise only 23% of head coaching positions. Why are women coaches – especially of women’s teams – being left out? We talked to 9 female and 12 male coaches of women’s and men’s teams and many of their own explanations suggest a view of fundamental and “natural” differences between men and women.

.

Talking to Coaches… Gender Matters

In general, the qualities of sport – competition, confidence, physical strength, aggression – are seen as masculine, while characteristics of cooperation, passivity, and dependency are coded feminine, raising suspicions about women’s capacity to excel. Masculine dominance has helped to define the parameters of what it means to be a coach.

Interestingly, coaching may be seen as an example of conflicting masculine roles. Given the low pay and high time commitment, coaching undermines the traditional male family role as breadwinner. As this male head women’s tennis coach explains,

I’ve been kind of lucky… I didn’t feel like I had to make a certain amount of money, X amount of dollars to be happy. So I was ok with where I was at salary wise… I think that the key to that is having a wife that also works, and that we can still make it happen, and sort of live the way we want to live and be happy.

Many of the men echoed the idea that without a spouse’s support, a coaching career would be difficult. Although respondents all felt women opt out of coaching due to family pressures, none felt that men needed to opt out to support their families. Arguably, the relationship between masculinity and athletics provides men with the social compensation necessary to remain in coaching in a way that does not operate for women.

Especially when asked why women don’t coach men, many of the respondents did not think women would have the strength, athleticism, authority, and leadership abilities to be effective men’s coaches. As a male head men’s soccer coach expresses:

I think the game is slightly different. The understanding of the nuances of the men’s game versus the women’s game… for a female to go into a men’s athletic team and command respect from those guys, it’s difficult. A female wouldn’t be able to step in and play seven versus seven and be able to play at the same level. Not technically, not tactically, I mean simply physically…just the strength factor.

Other arguments highlight the assumed biological connection between men and leadership. A female assistant women’s soccer coach argued that “the leadership gene is much more apparent in guys, it’s much more inherent in them.” Additionally challenging is the perception that taking orders and guidance from a female threatens masculinity and calls into question male superiority in a male dominated field. A former male head golf coach notes,

A woman coach is going to have to work harder to gain respect from a guy player than a male coach will have to work from a female player. … [Individuals are] raised to say if a guy’s leading, you give them a little benefit of the doubt. A woman has to prove herself, and until she does there’s going to be doubt.

By internalizing and enforcing stereotypes a gender pecking-order can be preserved. As this woman, an assistant women’s soccer coach, suggests, socialization improves men’s leadership ability:

When girls are socialized… it’s share, everyone in groups, be nice to everyone; guys are taught much more of competitiveness… a guy leader comes out in a group much easier… because in a girl’s environment it’s no one should be above anyone else… guys and girls are just different. They’re socialized different.

Stereotypes about men’s competitiveness and women’s need for emotional bonding were prevalent, and if these are carried into hiring decisions it is easy to see why male coaches are favored. Yet, if gender differences are so stark, we would expect to see same-sex coaching across the board, instead of the current disparity. Instead, this difference only legitimated women’s absence and was not used to question men’s presence as coaches of women’s teams. None of the women said they wanted to coach men’s teams and nor were they upset at being denied access to these positions. Respondents were more in favor of increasing women coaching women, but did not question or challenge any of the main gender stereotypes. This man, a former head men’s golf coach said,

I’m a fan of a woman coaching women’s sports, if skill levels are equal, because there are certain intangibles – I don’t understand the woman animal as well on certain things.

Shattering the “Glass Wall”?

Coaches we interviewed recognized the role that resources and opportunities played in incentivizing men into coaching women, but none challenged any aspect of the system. Respondents automatically buy into the “glass wall” such that 50 percent of jobs (those coaching men) are off-limits, thus if women coach approximately 50 percent of women’s teams, it’s “fair.” We see that unquestioned assumptions of gender difference supported perceptions that masculinity and men were superior to femininity and women. Twenty years ago scholars on this topic said it is beliefs in male athletic superiority that justify gender disparities in coaching, and according to these interviews little has changed. So, yes, observers should continue to call out the failures of Olympic commentators to treat women athletes equally, but as we say goodbye to Rio, let’s not forget how these issues are shaping coaches’ and athletes’ experiences every day.

Catherine Bolzendahl is a professor of sociology and the co-author of Counted Out: Same Sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family. Vanessa Kauffman is a PhD student. Both are at the University of California, Irvine. Jessica Broadfoot-(Lee) is an alum and was a member of the women’s tennis team and a two-time Big West Scholar-Athlete..

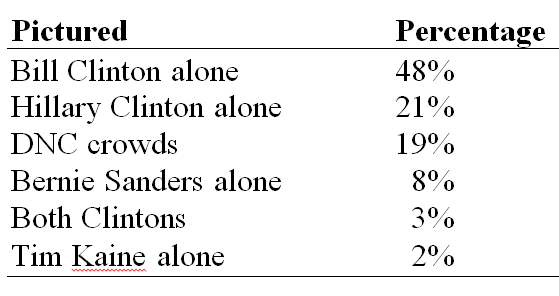

On Tuesday the first female presidential candidate was officially nominated by a major party. Newspaper headlines across the country referenced the historic event with headlines like “Historic First!” and “Clinton Makes History!” but a surprising number featured photographs of Bill instead of Hillary Clinton. I coded the pictures of each of the 266 newspapers that ran the story on the front page on July 27th (cataloged at

On Tuesday the first female presidential candidate was officially nominated by a major party. Newspaper headlines across the country referenced the historic event with headlines like “Historic First!” and “Clinton Makes History!” but a surprising number featured photographs of Bill instead of Hillary Clinton. I coded the pictures of each of the 266 newspapers that ran the story on the front page on July 27th (cataloged at