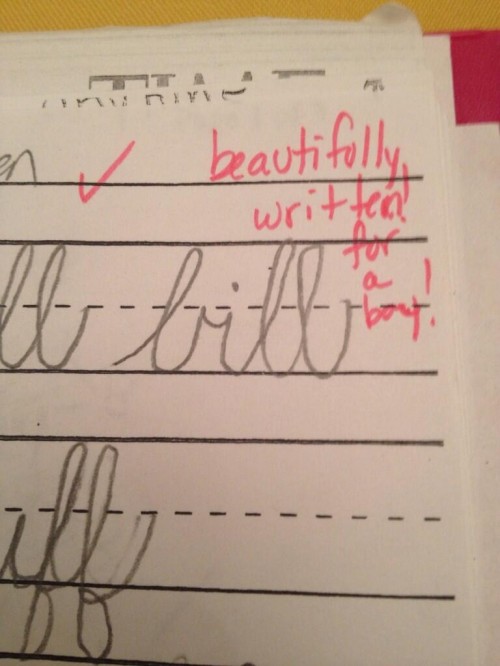

This week Meredith Kleykamp tweeted us a photo of a comment written on her 3rd grade son’s cursive homework. The teacher wrote: “beautifully written! for a boy!”

So what’s the message here?

Some argue that boys are slower than girls to develop the fine motor coordination that facilitates beautiful handwriting. I’ve never interrogated that research, but let’s assume, for sake of argument, that that’s true.

If it’s true, then maybe Kleykamp’s son’s handwriting really is beautiful “for a boy.” But does that make the teacher’s comment innocuous?

Kleykamp observes: “‘Beautifully written’ is sufficient to convey praise.” Then what additional message does the extra commentary send? Given a social context in which boys are encouraged to be unlike girls, Christopher Knorr thought the subtext might be: “you will be forced to choose between your penmanship and your masculinity.”

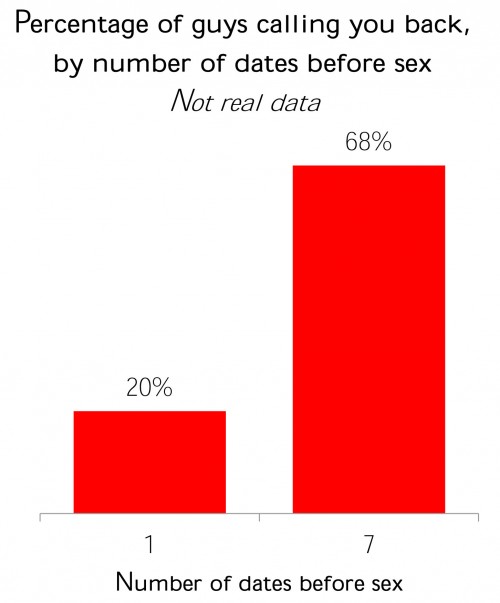

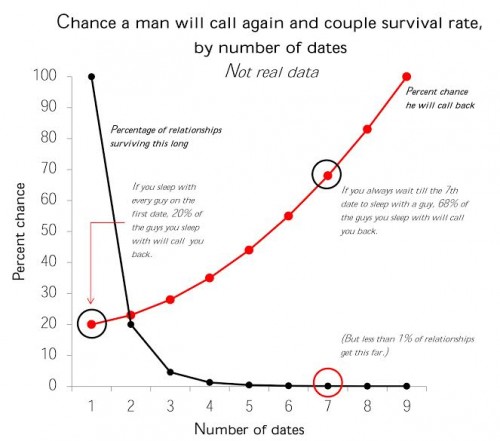

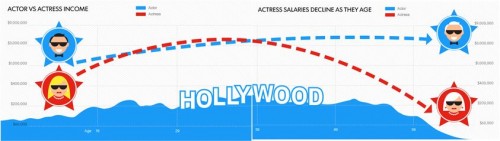

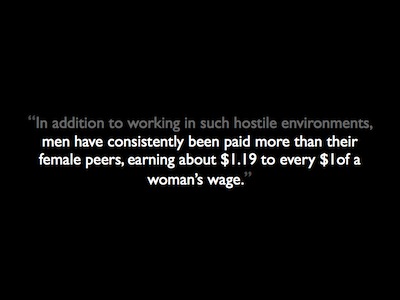

Scholars call these kinds of lessons the “hidden curriculum.” Here’s another shocking example.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.