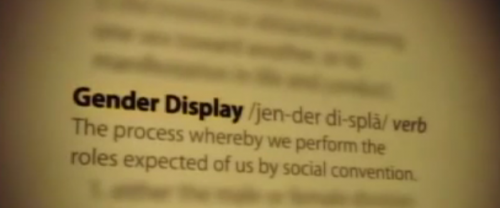

S. Alfonzo sent us a link to the abridged version of The Codes of Gender, in which Sut Jhally, known for a number of documentaries on pop culture, analyzes current messages about masculinity and femininity in advertising, applying the ideas of Erving Goffman regarding gender and cultural performance. Definitely worth the time to watch:

The Media Education Foundation has provided a full transcript and tips for using the film in the classroom.