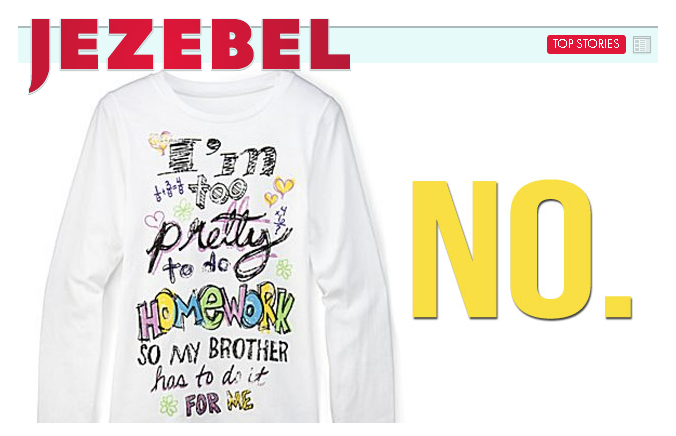

Cross-posted at Jezebel.

A year ago, I posted about street harassment — specifically, that form of harassment women often experience in which random men “compliment” us and then feel entitled to our gratitude and attention in return, and often lash out with a barrage of misogynistic comments if they don’t get it.

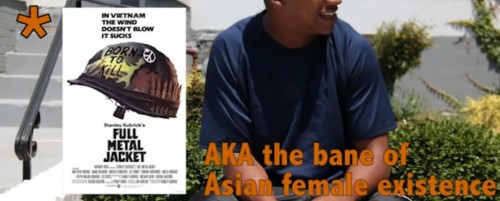

Caitlin Boston recently posted a video at Sweet.Sour.Satire that she made to highlight the specific kinds of comments Asian American women often face from strangers and even acquaintances. These experiences, both on the street and on dates, represent the intersection of generic sexism and the stereotype of the submissive, hyper-feminized Asian woman, plus an added dash of conflating all Asians (and conflating Asians with Asian Americans) and assuming every Asian American woman’s heart will melt at hearing her date can eat with chopsticks.