This weekend I went to the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles to see the Beauty CULTure exhibit. The description of the show suggested a critical perspective on beauty:

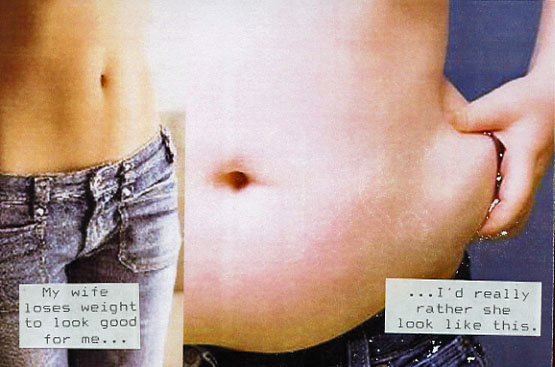

Through different lenses focused on the body beautiful, the exhibition examines both traditional and unconventional definitions of beauty, challenging stereotypes of gender, race and age. It explores the links between beauty and violence, glamour and sexuality and the cost (in its multiple meanings) of beauty.

The exhibit, to be fair, included a 30-minute documentary that touched on several critiques: the socialization of children, the pressure felt by adult women, the role of capitalism, and sizism and racism in the industry (featuring Lauren Greenfield’s work on girl culture and weight loss camps and Susan Anderson on child pageants).

But the actual photographs in the exhibit overwhelmingly affirmed instead of challenged our beauty culture. While the four images above, highlighted at the website, include an Asian woman, an older woman, and a picture of a child beauty pageant contestant designed to make us question how we raise children, the actual photographs were mostly conventionally-attractive, white, thin professional models glamorously outfitted, posed, and lit. These photographs outnumbered those that included women of color, older women, “plus-size” women, and critical images (e.g., photos of cosmetic surgeries) by something like 10 to 1. I didn’t leave feeling like I’d gained some perspective on the crushing pressure to be “perfect”; I left feeling like I’d flipped through a Cosmopolitan, awash in idealized images of female beauty, and more consciously aware of my deficiencies than when I arrived.

I say, skip it.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.