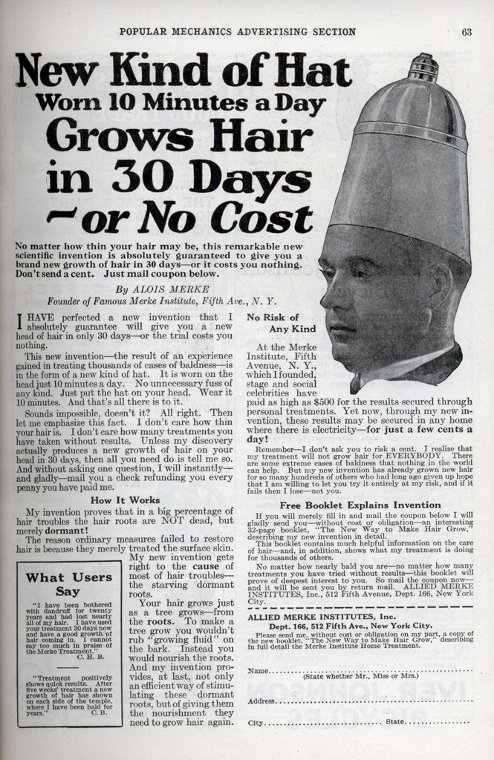

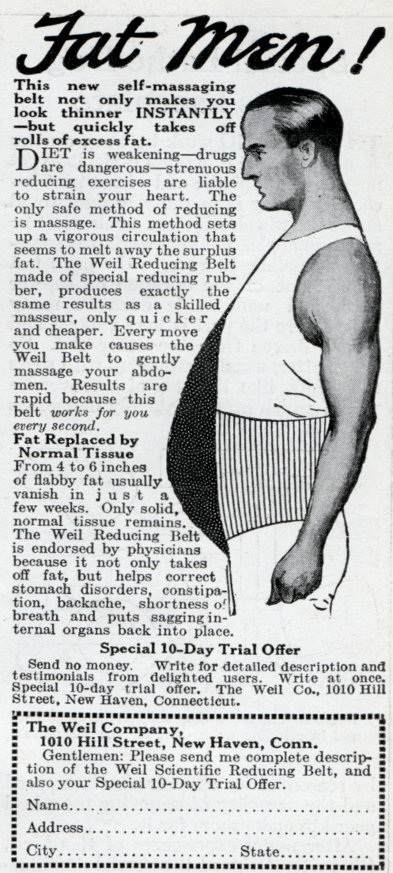

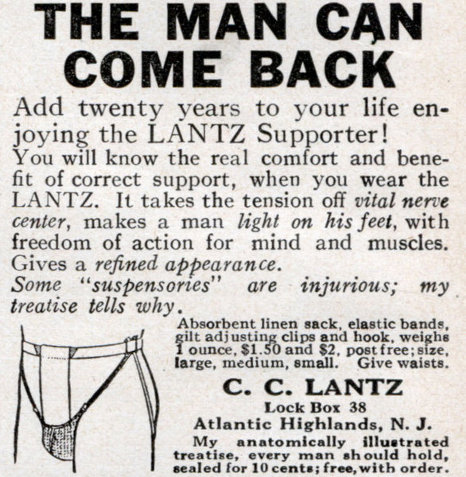

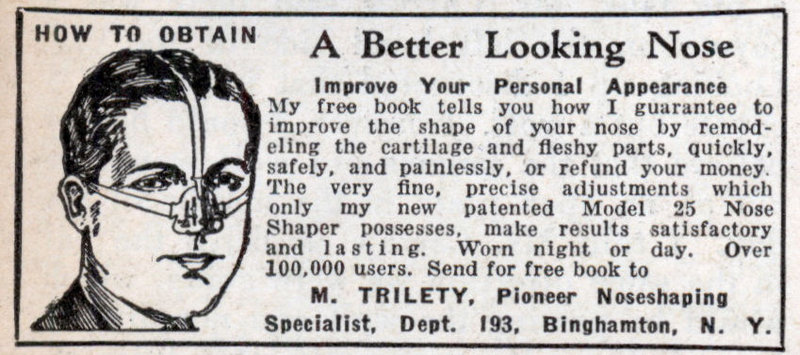

The vintage ads from The Art of Manliness, submitted by Dmitrity T.M., reveal that we have been trying to use technology to change our appearance for quite some time. Cosmetic surgeries are a brave new world of personal body modification, but they do not represent a break from the past, so much as a historical trajectory.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.